Transcript

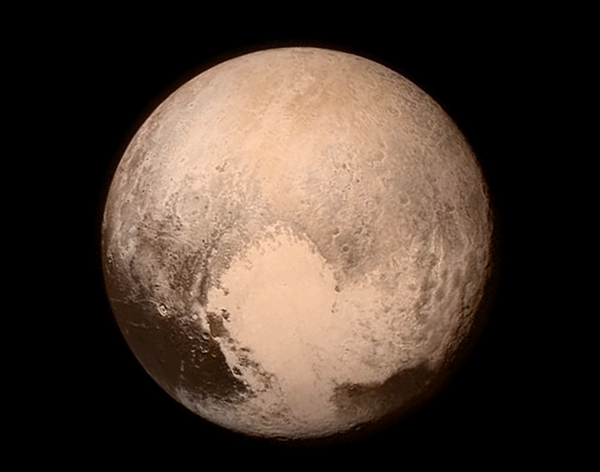

Humanity recently captured the first close-up views of the Pluto system through the eyes of the New Horizons spacecraft.

The mission was necessary because, frankly, Pluto doesn’t look like much from Earth. It glows at 14th magnitude, making it a thousand times dimmer than the faintest objects visible with naked eyes. Even the sharp eye of the Hubble Space Telescope reveals little more than mottled patches of white, orange, and black.

It doesn’t appear bright or show much detail for two reasons. First, it’s tiny, with a diameter of just 1,473 miles (2,370 kilometers) and a mass 500 times smaller than Earth’s. Second, Pluto lies far away. Its 248-year orbit keeps it at an average distance of 3.67 billion miles (5.91 billion kilometers) from the Sun. From this great distance, the Sun appears as no more than a point of light, although it would be a brilliant one, shining hundreds of times brighter than a Full Moon does from Earth.

As you might guess, this distant world wasn’t easy to find. American astronomer Clyde Tombaugh, a 24-year-old former farmboy from Kansas, discovered Pluto not long after joining the staff at Lowell Observatory in Arizona. Using a 13-inch telescope, he took pictures of the sky, returning to the same region every few days. While comparing two images of the constellation Gemini taken in January 1930, he spotted a faint dot that changed position relative to the fixed stars. Marked by an arrow in these images, the object’s movement was a telltale sign of a solar system object. Subsequent observations showed that the object lay well beyond Neptune — the ninth planet had been found.

But Pluto seemed an oddball almost from the start. Once astronomers pinned down its path around the Sun, they found it had the most elongated orbit of any planet. At its nearest, it lies closer to the Sun than Neptune. And Pluto’s orbit tips significantly to the plane of all the other planets. Combine that with its small size, and Pluto sticks out like a sore thumb.

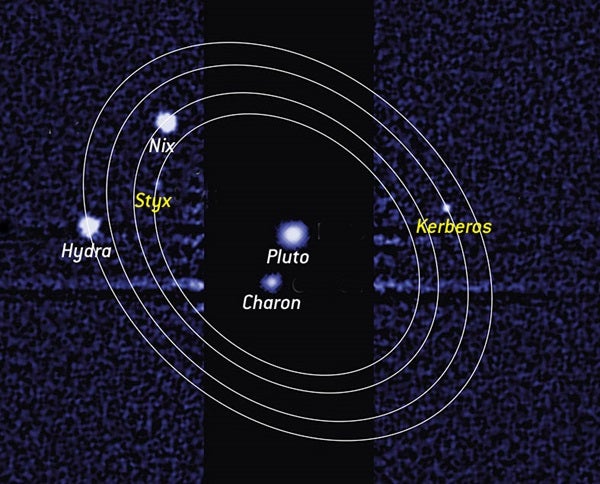

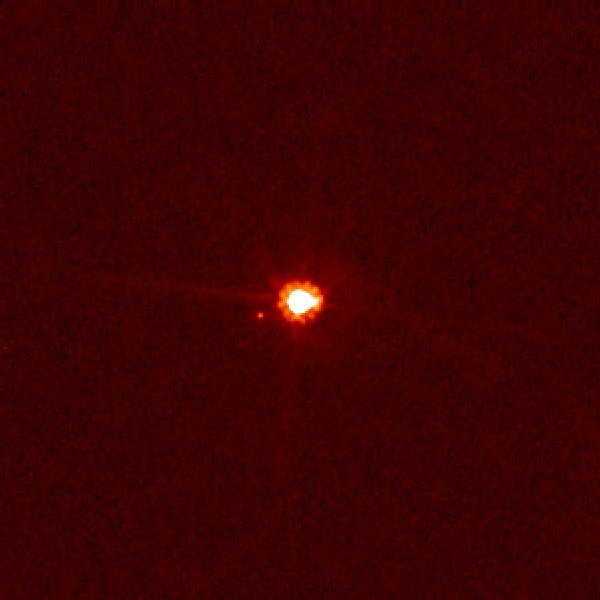

The distant world does have planet-like characteristics, however. In 1978, astronomers discovered a large moon that they called Charon. In this Hubble image, the first that clearly separated the closely orbiting worlds, Charon appears to Pluto’s upper right. Then, in 2005, scientists using Hubble found two smaller moons. Researchers quickly dubbed these Nix and Hydra.

Pluto’s surface hovers at a temperature of –387° Fahrenheit (–233° Celsius) and is covered with nitrogen-rich ices and at least one patch of carbon monoxide frost. The icy patches appear light in these Hubble views, which depict different hemispheres. Pluto even has a thin, nitrogen-rich atmosphere.

Astronomers have since cataloged more than 1,500 Kuiper Belt objects and expect the region holds at least 100,000 icy worlds. Several have diameters and masses that approach that of Pluto. This graphic shows the outer solar system along with the largest Kuiper Belt objects. Note how some have orbits similar to Pluto’s while others, particularly Eris and Sedna, are much more elongated. Astronomers think the objects in the belt formed in the region of the giant planets and later were flung into their current orbits when Uranus and Neptune migrated outward.

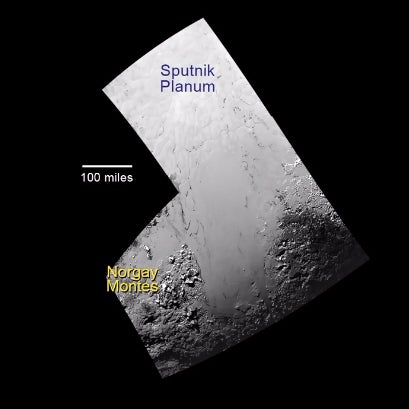

New Horizons also captured close-up views of Charon. It’s a geological paradise, with enough terrain types to keep scientists busy for years. A series of troughs and cliffs stretch 600 miles (1,000 kilometers) across the center of the disk. A vast canyon some 4 to 6 miles (7 to 9 km) deep scars the moon’s edge at about the 2 o’clock position. After the probe flew past Pluto, it turned its camera back toward the planet when it passed in front of the Sun. The resulting image revealed the world’s tenuous atmosphere as a thin glowing ring. New Horizons will take more than a year to send back all of its observations, and scientists will need plenty of additional time to understand them all.