The results show that these speedy electrons gain extra energy from changing magnetic fields far from the origin of the substorm that causes them. THEMIS, which consists of five orbiting satellites, helped provide these insights when three of the spacecraft traveled through a large substorm February 15, 2008. This allowed scientists to track changes in particle energy over a large distance. The observations were consistent with numerical models showing an increase in energy due to changing magnetic fields, a process known as betatron acceleration.

“The origin of fast electrons in substorms has been a puzzle,” said Maha Ashour-Abdalla from the University of California, Los Angeles. “It hasn’t been clear until now if they got their burst of speed in the middle of the storm, or from some place further away.”

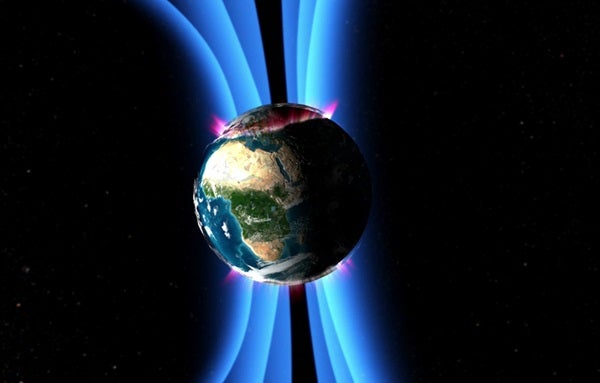

Substorms originate opposite the Sun on Earth’s “night side,” at a point about a third of the distance to the Moon. At this point in space, energy and particles from the solar wind store up over time. This is also a point where the more orderly field lines near Earth — where they look like two giant ears on either side of the globe, a shape known as a dipole because the lines bow down to touch Earth at the two poles — can distort into long lines and sometimes pull apart and “reconnect.” During reconnection, the stored energy is released in explosions that send particles out in all directions. But reconnection is a magnetic phenomenon and scientists don’t know the exact mechanism that creates speeding particles from that phenomenon.

“For 30 years, one of the questions about the magnetic environment around Earth has been, ‘How do magnetic fields give rise to moving, energetic particles’?” said Melvyn Goldstein from NASA’s Goddard Space Flight Center in Greenbelt, Maryland. “We need to know such things to help plan the next generation of reconnection research instruments such as the Magnetospheric MultiScale mission (MMS) due to launch in 2014. MMS needs to look in the right place and for the correct signatures of particle energization.”

In the early 1980s, scientists hypothesized that the quick, high-energy particles might get their speed from rapidly changing magnetic fields. Changing magnetic fields can cause electrons to zoom along a corkscrew path by the betatron effect.

Electrons moving toward Earth from a substorm will naturally cross a host of changing magnetic fields as those long, stretched field lines far away from Earth relax back to the more familiar dipole field lines closer to Earth, a process called dipolarization. Betatron acceleration causes the particles to gain energy and speed much farther away from the initial reconnection site. But in the absence of observations that could simultaneously measure data near the reconnection site and closer to Earth, the hypothesis was hard to prove or contradict.

THEMIS, however, was specifically designed to study the formation of substorms. It launched with five spacecraft that can be spread out over about 44,000 miles (70,800 kilometers) — a perfect tool for examining different areas of Earth’s magnetic environment at the same time. Near midnight on February 15, 2008, three of the satellites moving through Earth’s magnetic tail, about 36,000 miles (58,000 km) from Earth, traveled through a large substorm.

“I looked at the THEMIS data for that substorm,” said Ashour-Abdalla, “and saw there was a direct correlation of the increased particle energy at the origin with the region of dipolarization nearer to Earth.”

To examine the data, Ashour-Abdalla and a team of researchers from UCLA, Nanchang University in China, NASA’s Goddard Space Flight Center, and the University of Maryland, Baltimore, used their expertise with computer modeling to simulate the complex dynamics that occur in space. The team began with spacecraft data from the European Space Agency (ESA) mission called Cluster that was in the solar wind at the time of the substorm. Using these observations of the solar environment, they modeled large-scale electric and magnetic fields in space around Earth; then they modeled the future fate of the various particles observed.

When the team looked at their models, they saw that electrons near the reconnection sites didn’t gain much energy. But as they looked closer to Earth, where the THEMIS satellites were located, their model showed particles that had some 10 times as much energy — just as THEMIS had observed.

This is consistent with the betatron acceleration model. The electrons gain a small amount of energy from the reconnection and then travel toward Earth, crossing many changing magnetic field lines. These fields produce betatronic acceleration just as Kivelson predicted in the early 1980s, speeding the electrons up substantially.

“This research shows the great science that can be accomplished when modelers, theorists, and observationalists join forces,” said Larry Kepko from Goddard. “THEMIS continues to yield critical insights into the dynamic processes that produce the space weather that affects Earth.”

reconnection causes energy to be rapidly released along the field lines

causing the auroras to brighten.

The results show that these speedy electrons gain extra energy from changing magnetic fields far from the origin of the substorm that causes them. THEMIS, which consists of five orbiting satellites, helped provide these insights when three of the spacecraft traveled through a large substorm February 15, 2008. This allowed scientists to track changes in particle energy over a large distance. The observations were consistent with numerical models showing an increase in energy due to changing magnetic fields, a process known as betatron acceleration.

“The origin of fast electrons in substorms has been a puzzle,” said Maha Ashour-Abdalla from the University of California, Los Angeles. “It hasn’t been clear until now if they got their burst of speed in the middle of the storm, or from some place further away.”

Substorms originate opposite the Sun on Earth’s “night side,” at a point about a third of the distance to the Moon. At this point in space, energy and particles from the solar wind store up over time. This is also a point where the more orderly field lines near Earth — where they look like two giant ears on either side of the globe, a shape known as a dipole because the lines bow down to touch Earth at the two poles — can distort into long lines and sometimes pull apart and “reconnect.” During reconnection, the stored energy is released in explosions that send particles out in all directions. But reconnection is a magnetic phenomenon and scientists don’t know the exact mechanism that creates speeding particles from that phenomenon.

“For 30 years, one of the questions about the magnetic environment around Earth has been, ‘How do magnetic fields give rise to moving, energetic particles’?” said Melvyn Goldstein from NASA’s Goddard Space Flight Center in Greenbelt, Maryland. “We need to know such things to help plan the next generation of reconnection research instruments such as the Magnetospheric MultiScale mission (MMS) due to launch in 2014. MMS needs to look in the right place and for the correct signatures of particle energization.”

In the early 1980s, scientists hypothesized that the quick, high-energy particles might get their speed from rapidly changing magnetic fields. Changing magnetic fields can cause electrons to zoom along a corkscrew path by the betatron effect.

Electrons moving toward Earth from a substorm will naturally cross a host of changing magnetic fields as those long, stretched field lines far away from Earth relax back to the more familiar dipole field lines closer to Earth, a process called dipolarization. Betatron acceleration causes the particles to gain energy and speed much farther away from the initial reconnection site. But in the absence of observations that could simultaneously measure data near the reconnection site and closer to Earth, the hypothesis was hard to prove or contradict.

THEMIS, however, was specifically designed to study the formation of substorms. It launched with five spacecraft that can be spread out over about 44,000 miles (70,800 kilometers) — a perfect tool for examining different areas of Earth’s magnetic environment at the same time. Near midnight on February 15, 2008, three of the satellites moving through Earth’s magnetic tail, about 36,000 miles (58,000 km) from Earth, traveled through a large substorm.

“I looked at the THEMIS data for that substorm,” said Ashour-Abdalla, “and saw there was a direct correlation of the increased particle energy at the origin with the region of dipolarization nearer to Earth.”

To examine the data, Ashour-Abdalla and a team of researchers from UCLA, Nanchang University in China, NASA’s Goddard Space Flight Center, and the University of Maryland, Baltimore, used their expertise with computer modeling to simulate the complex dynamics that occur in space. The team began with spacecraft data from the European Space Agency (ESA) mission called Cluster that was in the solar wind at the time of the substorm. Using these observations of the solar environment, they modeled large-scale electric and magnetic fields in space around Earth; then they modeled the future fate of the various particles observed.

When the team looked at their models, they saw that electrons near the reconnection sites didn’t gain much energy. But as they looked closer to Earth, where the THEMIS satellites were located, their model showed particles that had some 10 times as much energy — just as THEMIS had observed.

This is consistent with the betatron acceleration model. The electrons gain a small amount of energy from the reconnection and then travel toward Earth, crossing many changing magnetic field lines. These fields produce betatronic acceleration just as Kivelson predicted in the early 1980s, speeding the electrons up substantially.

“This research shows the great science that can be accomplished when modelers, theorists, and observationalists join forces,” said Larry Kepko from Goddard. “THEMIS continues to yield critical insights into the dynamic processes that produce the space weather that affects Earth.”

reconnection causes energy to be rapidly released along the field lines

causing the auroras to brighten.