Targets for July 17–24, 2014

Naked eye and Binoculars: Double stars Antares (Alpha [α] Scorpii) and Ras Algethi (Alpha Herculis)

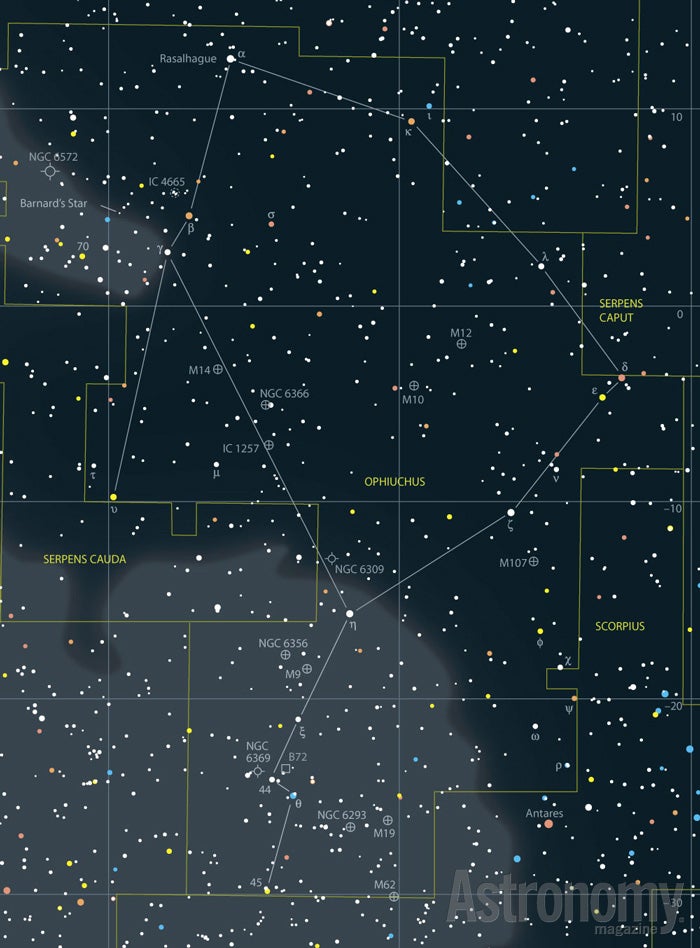

Small telescope: Globular clusters M19 and M62

Large telescope: The Box Nebula (NGC 6309)

For this week’s naked-eye object, I’ve chosen two stars separated by one-quarter of the sky: Antares (Alpha [α] Scorpii) and Ras Algethi (Alpha Herculis). Because it’s brighter, start with Antares.

Normally, a magnitude 5.4 star — Antares B — wouldn’t be hard to find. In this case, however, it sits only 2.6″ from magnitude 1.1 Antares A, so, although you can find Antares with your naked eye, you’ll need an 8-inch telescope and high power to split its two components cleanly. When you do, the contrast effect will present a bright-orange primary with an olive-green companion. I love this pair!

This brilliant star’s name comes from the pairing of two Greek words, literally “anti” and the Greek god “Ares.” Put together, they refer to a star that is the “rival of Mars” in color.

Hercules’ Alpha star, Ras Algethi, is also one I enjoy observing, and I think you will too. Because of a wonderful contrast effect, the magnitude 5.4 secondary star appears olive-green. The primary, which shines at magnitude 3.5, appears yellow with a trace of orange. The separation between the two stars is 4.6″.

“Ras Algethi” means the Kneeler’s head, which refers to the way the mythological figure Hercules is represented kneeling in the constellation of the same name. Famed 19th-century observer Admiral William Smyth calls this pair orange and either emerald or bluish green, later saying this star is a “lovely object, one of the finest in the heavens.”

Two non-round globulars

This week’s small-telescope targets are globular clusters M19 and M62 in Ophiuchus. To find M19, look 4.5° west-southwest of magnitude 3.3 Theta (θ) Ophiuchi.

Seen on photographs or at high enough magnification, all globular clusters exhibit some degree of oblateness (flattening) because they rotate. M19, however, appears more flattened than any other Milky Way globular. Astronomers initially thought its ellipticity was real, but more recent investigations have shown that this is an illusion created by foreground absorption of starlight on its eastern and western edges.

Whatever the reason, you’ll spot the oval form of magnitude 6.7 M19 through any telescope. The cluster has a diameter of 13.5′. A 4-inch scope at 250x will resolve less than 20 of its stars. Through an 11-inch telescope, you’ll see 50 stars of nearly equal brightness. The brightest star, magnitude 11.2 GSC 6819:282, sits 1′ northwest of the cluster’s center.

You’ll find our second globular, M62, as far south in Ophiuchus as you can go, 5.8° east-southeast of magnitude 2.8 Tau (τ) Scorpii. It shines at magnitude 6.7 and measures 14.1′ across.

Although astronomers classify this as a “globular” cluster, you’ll immediately notice — just like with M19 — that it’s not spherical. M62’s most radical departure from a round shape lies in a fan of stars that extends from the northwestern edge.

Through a 4-inch telescope at 200x, the entire border appears irregular, and the southeast side looks flat. M12’s core is bright and concentrated.

Admiral Smyth, writing in the Cycle of Celestial Objects (1844), quotes an odd statement by a famous astronomer: “Sir William Herschel, who first resolved it, pronounced it a miniature of Messier’s No. 3, and adds, ‘By the 20-feet telescope, which at the time of these observations was of the Newtonian construction, the profundity of this cluster is of the 734th order.'”

Look for the box

This week’s large-telescope target is the Box Nebula (NGC 6309), a planetary nebula in Ophiuchus. It isn’t big (only 18″ across), bright (a dim magnitude 11.5), or famous. To large-telescope users, this may sound like fun. If you think so, look for the Box Nebula 1.6° west of magnitude 4.3 Nu (ν) Serpentis.

One thing going for it is that the Box Nebula doesn’t spread its light across a large area. NGC 6309 is tiny, and that’s a plus in this case because the small size keeps the planetary’s surface brightness high.

Through an 11-inch telescope, crank the magnification past 250x to identify the box’s shape. A nebula filter such as an Oxygen-III (OIII) will help a lot. Some observers use lower powers and combine the slightly elongated NGC 6309 with the 9th-magnitude star 1′ to its northwest to form the Exclamation Point Nebula. Try it yourself.

If you’re lucky enough to view the Box Nebula through a telescope with 16 inches of aperture or more, you’ll see tiny but distinct details at magnifications approaching 500x. For example, the northwestern half appears slightly brighter than the southwestern part. Faint nebulous tendrils roughly one-quarter the Box’s length extend outward from the northwestern edge. And the central star will pose no problem. That magnitude 14 point of light lies at the nebula’s center.

Oh, by the way, this is actually one of two celestial wonders amateur astronomers call the Box Nebula. The other is NGC 6445 in Sagittarius.

Expand your observing at Astronomy.com

StarDome

Check out Astronomy.com’s interactive StarDome to see an accurate map of your sky. This tool will help you locate this week’s targets.

The Sky this Week

Get a daily digest of celestial events coming soon to a sky near you.

Observing Talk

After you listen to the podcast and try to find the objects, be sure to share your observing experience with us by leaving a comment at the blog or in the Reader Forums.