On November 23, the Large Hadron Collider (LHC) circulated two beams simultaneously for the first time, allowing the operators to test the synchronization of the beams and giving the experiments their first chance to look for proton-proton collisions. With just one bunch of particles circulating in each direction, the beams can be made to cross in up to two places in the ring. From early in the afternoon, the beams were made to cross at points 1 and 5, home to the A Toroidal LHC Apparatus (ATLAS) and Compact Muon Solenoid (CMS) detectors, both of which were on the lookout for collisions. Later, beams crossed at points 2 and 8, the Large Ion Collider Experiment (ALICE) and the Large Hadron Collider beauty (LHCb).

“It’s a great achievement to have come this far in so short a time,” said CERN Director General Rolf Heuer. “But we need to keep a sense of perspective — there’s still much to do before we can start the LHC physics program.”

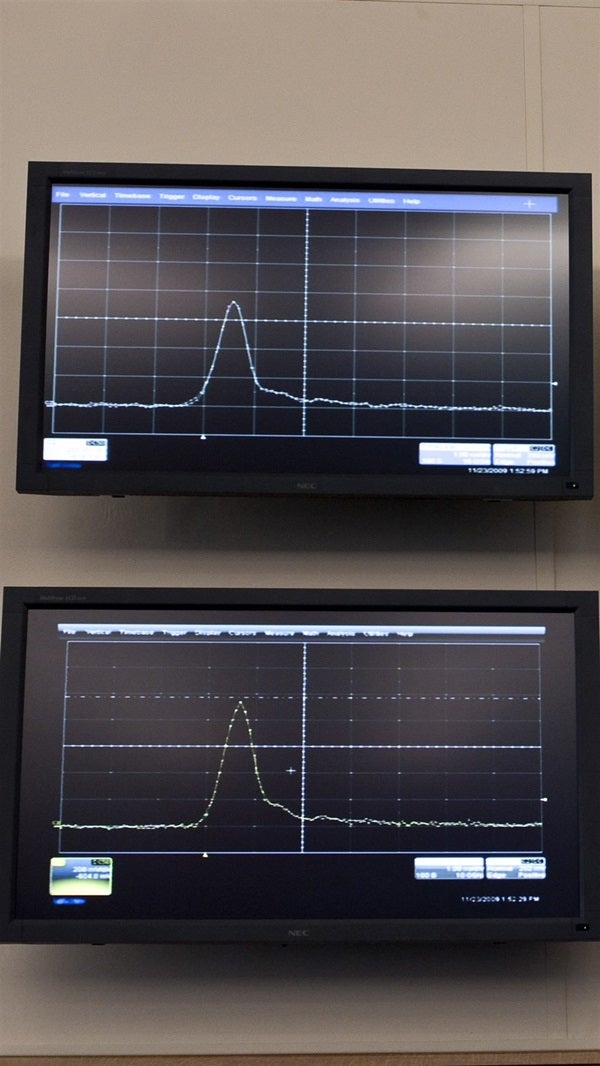

Beams were first tuned to produce collisions in the ATLAS detector, which recorded its first candidate for collisions November 23. Later, the beams were optimized for CMS. In the evening, ALICE had the first optimization followed by LHCb.

“This is great news, the start of a fantastic era of physics and hopefully discoveries after 20 years’ work by the international community to build a machine and detectors of unprecedented complexity and performance,” said Fabiola Gianotti, ATLAS spokesperson.

“The tracks we’re seeing are beautiful,” said Andrei Golutvin, LHCb spokesperson. “We’re all ready for serious data-taking in a few days.”

These developments come just 3 days after the LHC restart, demonstrating the excellent performance of the beam control system. Since the start-up, the operators have been circulating beams around the ring alternately in one direction and then the other at the injection energy of 450 GeV. The beam lifetime has gradually been increased to 10 hours, and today beams have been circulating simultaneously in both directions, still at the injection energy.

“Achieving low-energy collisions in the LHC so quickly after the re-start is a huge boost for the worldwide particle physics community,” said Norman McCubbin, head of particle physics at the Science and Technology Facilities Council’s Rutherford Appleton Laboratory.

“The CERN accelerator team is doing a tremendous job, and I congratulate them on achieving this vital step on the way to full operation of the LHC,” said John Womersley, director of science programs at STFC. “As a scientist who has worked on this kind of machine, I understand the challenges involved. From here, the CERN team will be working on increasing the number of particles in the beams and gradually ramping up the energy of these particles. The LHC will soon be the highest energy particle accelerator in the world, and in 2010 we can expect to see it start delivering new science.”

Next on the schedule is an intense commissioning phase aimed at increasing the beam intensity and accelerating the beams. By Christmas, the LHC should reach 1.2 TeV per beam and provide good quantities of collision data for the experiments’ calibrations.