About half of the stars in our Milky Way Galaxy are, unlike our Sun, part of a binary system in which two stars orbit each other. Most likely, the stars in these systems were formed close together and have been in orbit around each other from birth onward. Scientists always thought that if binary stars form too close to each other, they would quickly merge into one single, bigger star. This was in line with many observations taken over the past three decades showing the abundant population of stellar binaries, but none with orbital periods shorter than five hours.

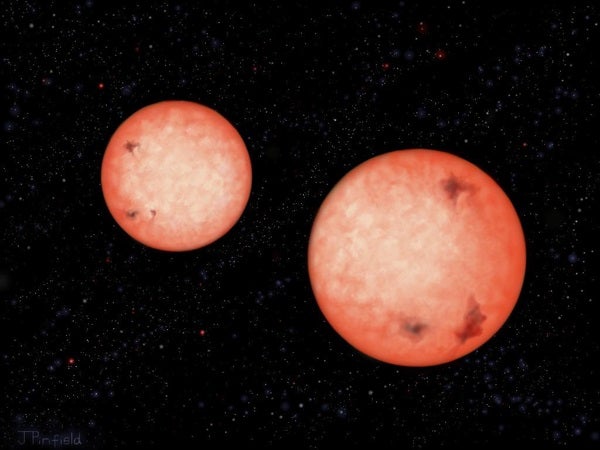

For the first time, the team have investigated binaries of red dwarfs, stars up to 10 times smaller and a thousand times less luminous than the Sun. Although they form the most common type of star in the Milky Way, red dwarfs do not show up in normal surveys because of their dimness in visible light.

For the past five years, UKIRT has been monitoring the brightnesses of hundreds of thousands of stars, including thousands of red dwarfs, in near-infrared light, using its state-of-the-art Wide-Field Camera. This study of cool stars in the time domain has been a focus of the European (FP7) Initial Training Network “Rocky Planets Around Cool Stars” (RoPACS), which studies planets and cool stars.

“To our complete surprise, we found several red dwarf binaries with orbital periods significantly shorter than the five-hour cut-off found for Sun-like stars, something previously thought to be impossible,” said Bas Nefs from Leiden Observatory in the Netherlands, lead author of the study. “It means that we have to rethink how these close-in binaries form and evolve.”

Because stars shrink in size early in their lifetime, the fact that these very tight binaries exist means that their orbits must also have shrunk as well since their birth; otherwise, the stars would have been in contact early on and have merged. However, it is not at all clear how these orbits could have shrunk by so much.

One possible answer to this riddle is that cool stars in binary systems are much more active and violent than previously thought.

It is possible that the magnetic field lines radiating out from the cool star companions get twisted and deformed as they spiral in toward each other, generating the extra activity through stellar wind, explosive flaring, and starspots. Powerful magnetic activity could apply the brakes to these spinning stars, slowing them down so that they move closer together.

“Without UKIRT’s superb sensitivity, it wouldn’t have been possible to find these extraordinary pairs of red dwarfs,” said David Pinfield of the University of Hertfordshire in the United Kingdom. “The active nature of these stars and their apparently powerful magnetic fields has profound implications for the environments around red dwarfs throughout our galaxy.”