Uranus’ distinct bluish hue shines through in this 2011 Hubble Space Telescope image. The small white splotch is an aurora in the ice giant’s atmosphere.

Saturn and Mars grace the twilight as September evenings unfold. Jupiter becomes the main attraction in the morning sky as it climbs high before dawn. Its companion for the past several months, brilliant Venus, now hangs lower in the sky. The morning “star” still offers early risers a treat, however, particularly when it passes near the fine Beehive star cluster in mid-September. In the solar system’s outer reaches, Uranus and Neptune put on fine shows all night.

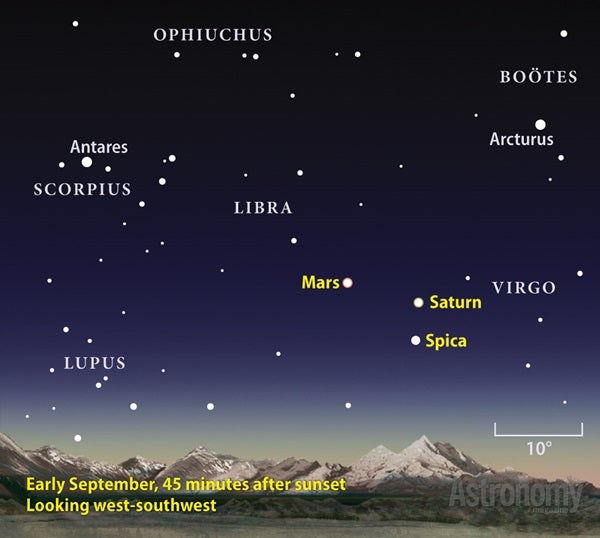

Our tour of the solar system begins in evening twilight, where three planets vie for attention. The lead player remains Saturn. The ringed planet lies about 10° high in the west-southwest an hour after the Sun goes down in early September. Shining at magnitude 0.8, it appears brighter than any other object in this part of the sky. Virgo’s brightest star, magnitude 1.0 Spica, is a close second. You can find this luminary 5° below Saturn.

The star and planet sink lower with each passing day. By month’s end, Saturn dips below the horizon just 60 minutes after sunset. It will pass behind the Sun in late October and return to view before dawn a few weeks later.

Saturn’s low altitude means we must view it through more of Earth’s turbulent atmosphere, so sharp views through a telescope will be hard to come by. Still, the ringed planet looks mesmerizing and certainly is worth observing at low to medium magnification. In early September, the ring system spans 36″ and tilts 14° to our line of sight. By the time Saturn returns to view in November, the rings will tilt 18° and appear even more spectacular.

If you look approximately 10° to Saturn’s left in early September, your eyes will land on Mars. The Red Planet shines at magnitude 1.2, slightly but noticeably fainter than Saturn. Mars’ ruddy glow contrasts nicely with the ringed planet’s yellowish hue, particularly if you take advantage of the extra light-gathering power binoculars provide.

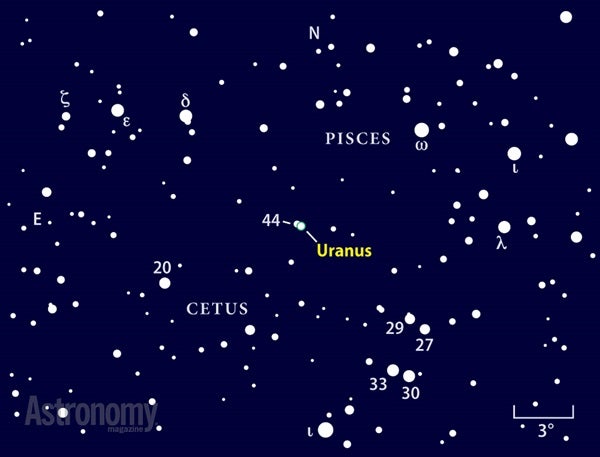

Uranus glows at magnitude 5.7 during September. It lies near the border between Pisces and Cetus at opposition on the 29th. Astronomy: Roen Kelly

The two planets don’t stay close for long. Mars moves rapidly eastward against the starry background and travels from eastern Virgo through most of Libra this month. On September 15, the planet passes 1° south of the fine double star Zubenelgenubi (Alpha [α] Librae). Four days later, a waxing crescent Moon lies a couple of degrees to Mars’ left. Unfortunately, the planet doesn’t offer much to observers who target it through a telescope. Its 5″-diameter disk shows little, if any, detail.

Innermost Mercury makes a brief appearance low in the west as September ends. The planet stands 14° east of the Sun on the 30th, but most of that distance runs parallel to the horizon and not perpendicular. From 40° north latitude, Mercury appears a mere 2° high 20 minutes after sunset. Observers will need a flat, unobstructed horizon and a pristine sky to pick out the planet. Its one saving grace is that it shines brightly at magnitude –0.4.

Pluto resides less than 1° southwest of the easy-to-see open star cluster M25 in northern Sagittarius. This so-called dwarf planet is one of the largest solar system objects known beyond Neptune. Pluto lies far enough from the Sun, however, that it glows faintly at magnitude 14.1.

The distant world’s westerly motion relative to the background stars halts September 17. It then heads slowly east and a bit south and, by the 30th, arrives within 7′ of the 8th-magnitude star HD 170120, which is noticeable for its distinct orange color when viewed through a telescope. Although Pluto is difficult to see visually in an instrument smaller than 10 inches in aperture, it’s a nice target for a CCD camera. In late September, aim at the orange star and take one 30-second image on two or three consecutive nights. You’ll easily capture Pluto and its nightly motion.

Neptune currently lies 55° east of Pluto in the constellation Aquarius. The eighth planet reached opposition and peak visibility in late August, and it remains a fine target through binoculars and telescopes all night.

You can find it in the same binocular field as both 4th-magnitude Iota (ι) Aquarii and 5th-magnitude 38 Aqr (which resides 2.5° north-northeast of Iota). The planet begins September nearly 1° due east of the latter star and closes the month just 22′ southeast of it.

Mars, Saturn, and Spica dip deeper into the twilight during September, but views early in the month should still be impressive. Astronomy: Roen Kelly

Neptune glows at magnitude 7.8, just within range of hand-held 7×50 binoculars. When mounted on a tripod, the same binoculars easily reveal Neptune as well as many fainter stars. Use your telescope and a high-power eyepiece to see the planet’s 2.4″-diameter disk and blue-gray color.

Head one constellation farther east, and you’ll land on the current home of Uranus. This planet reaches opposition September 29, when it lies opposite the Sun in our sky and remains visible from sunset to sunrise. This configuration also brings Uranus closest to Earth, so it glows brighter and appears larger through a telescope than at any other time this year. One day after opposition, the Full Moon passes 5° north of the planet.

Uranus peaks at magnitude 5.7, although it doesn’t appear perceptibly fainter at any other time this month. Its magnitude makes it just bright enough to see with naked eyes if you observe under a dark sky. Binoculars or a telescope show the planet with ease. A telescope reveals Uranus’ disk, which spans 3.7″ and displays a distinct blue-green hue.

You can find the planet on the border between Pisces and Cetus. It lies near the equally bright star 44 Piscium. On September 22, Uranus appears 1.4′ due east of the star, and the two will look like a bright double through a telescope. Their distance remains the same on the following night, but the planet then appears southwest of the star. By month’s end, 18′ separate the two objects.

Brilliant Jupiter dramatically changes the familiar appearance of Taurus the Bull, standing less than 10° northeast of the Hyades star cluster all month. Although the giant planet rises before midnight local daylight time, the best views come as it climbs higher before dawn. It shines

at magnitude –2.4, making it the brightest night-sky object other than the Moon and Venus. The Last Quarter Moon passes within 1° of Jupiter the morning of September 8.

Venus meets the swarm of stars known as the Beehive Cluster (M44) in mid-September. Binoculars deliver great views, particularly when a waning crescent Moon joins the scene on the 12th. Astronomy: Roen Kelly

The planet puts on a show for those who view it through a telescope. Jupiter’s equatorial diameter grows 10 percent this month, from 39″ to 43″, as it approaches Earth. The gas giant’s dynamic atmosphere is one of the solar system’s visual highlights, and it’s on display every clear night. The most prominent features are two dark equatorial belts that straddle a brighter zone and the Great Red Spot, which now appears a subtle pink. Under good conditions, a series of alternating belts and zones appears. Experienced observers patiently watch Jupiter over many minutes to catch occasional moments of great seeing, when fine details pop into view.

You need no experience to marvel at the planet’s four bright moons: Io, Europa, Ganymede, and Callisto. Their orbits carry them into different configurations each night and often from one hour to the next. Use the diagram at the bottom of page 40 to identify each moon.

Dazzling Venus rises around 3 a.m. local daylight time during September. It appears among the background stars of eastern Gemini on the 1st, some 9° south of 1st-magnitude Pollux. At magnitude –4.3, the planet outshines the star by more than 100 times.

Venus crosses into the decidedly fainter constellation Cancer on September 4. But a stunning alignment awaits observers September 12. That morning, a waning crescent Moon stands 4° southwest of Venus while the planet lies 3° southwest of the Beehive star cluster (M44). The scene should be nice with naked eyes, but binoculars will deliver the best views. On the next two mornings, Venus passes 2.5° south of the Beehive. The planet spends September’s final week in western Leo, not far from 1st-magnitude Regulus.

To see Venus well through a telescope, wait until twilight begins, which reduces the contrast between planet and sky. During September, Venus’ disk shrinks from 20″ to 16″ across while its phase waxes from 58 to 70 percent lit.

The autumnal equinox occurs at 10:49 a.m. EDT September 22. As Earth orbits our star, the Sun wanders against a backdrop of invisible constellations. It lies in Virgo at the equinox, at the precise point where the ecliptic crosses the celestial equator. This brings nearly equal portions of day and night to most places on Earth except at the poles, where the Sun takes all day to circle the horizon.

The Epsilon Perseid meteor shower should produce about five meteors per hour the night of September 9/10. Observers will have Moon-free viewing during late evening. Astronomy: Roen Kelly

Will Perseus erupt two months in a row?

September typically is a month of few meteors, particularly when compared with the activity associated with August’s Perseid shower. But there is hope. The International Meteor Organization (IMO) has identified a relatively new shower called the Epsilon Perseids. In 2008, observers saw an unexpected flurry of bright meteors emanating from Perseus. The shower remains active from September 4 to 14 and peaks the night of September 9/10.

For Northern Hemisphere viewers, Perseus rises in late evening. This leaves a few hours of dark skies before the Moon pokes above the horizon shortly after midnight local daylight time. Although the IMO doesn’t expect a repeat of the 2008 outburst, the only people who will know for sure are those watching the sky.

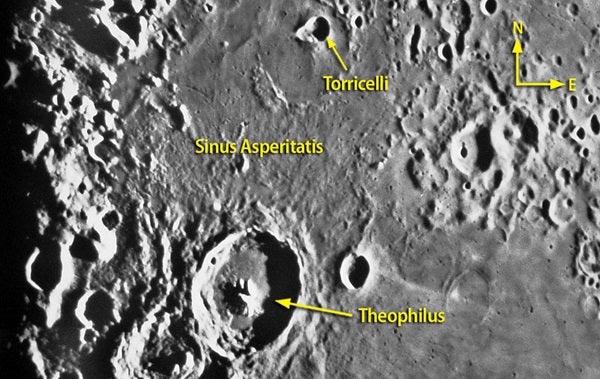

Sharp-edged crater Theophilus stands out shortly before First Quarter Moon. Look slightly north of this impact site for the jumbled terrain of Sinus Asperitatis and pear-shaped crater Torricelli. Consolidated Lunar Atlas/UA/LPL

Rough seas mark a crater’s debris

If there’s a best face to the Moon, it’s the thick crescent seen a day or two before First Quarter phase. Smooth “seas” seemingly sport large waves, big craters take your breath away, and small impact scars stand out by casting long shadows. On the evening of September 20, the dramatic Serpentine Ridge is sure to grab your attention. This feature snakes north-south across the eastern part of Mare Serenitatis (the Sea of Serenity). Geologically speaking, it’s a compression feature and not a frozen wave rippling through the lava.

Scan just south of the equator, and you’ll find Theophilus, a sharp-edged crater that spans approximately 60 miles. Although it remains largely under the cover of night on the 20th, the Sun rises above the crater’s rim on the 21st to produce a scene similar to the one pictured here. That’s the best time to examine its complex jumble of central peaks and slumped terraces on the crater’s walls. The impact that created Theophilus spread a rugged apron of debris northward into Mare Tranquillitatis (the Sea of Tranquility). Astronomers aptly named this region Sinus Asperitatis — the Bay of Roughness.

Also look closely at the unusual double crater Torricelli, located just north of Theophilus. Astronomers believe that its pear shape comes from a single glancing blow and not two unrelated events. Essentially, what was left of the impacting projectile blasted through the back wall as the crater was forming. Torricelli sits off-center in an ancient battered bowl filled to the brim with lava.

| When to view the planets | ||

| EVENING SKY | MIDNIGHT | MORNING SKY |

| Mercury (west) | Jupiter (east) | Venus (east) |

| Mars (southwest) | Uranus (southeast) | Jupiter (southeast) |

| Saturn (west) | Neptune (south) | Uranus (west) |

| Uranus (east) | ||

| Neptune (southeast) | ||

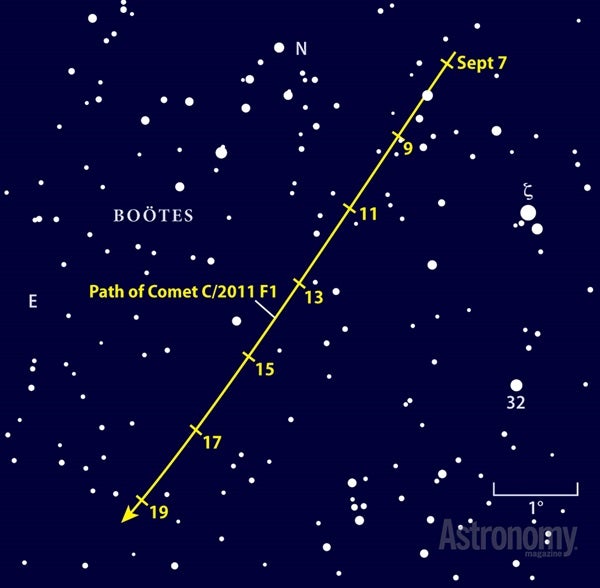

Comet C/2011 F1 (LINEAR) might reach 10th magnitude this month as it treks through southern Boötes. Your best looks will come when the Moon is gone from the evening sky around mid-September. Astronomy: Roen Kelly

A dirty snowball invades the Herdsman

Comet hunters have no time to lose after darkness falls this month. Head outside about 90 minutes after the Sun sets and find magnitude 0.0 Arcturus. This bright star lies low in the west and displays a noticeable orange hue. (Use the circular StarDome map on pages 38 and 39 to locate Arcturus.)

Eight degrees southeast of Arcturus lies 4th-magnitude Zeta (ζ) Boötis, our jumping off point for locating Comet C/2011 F1 (LINEAR). You’ll likely need a 6-inch or larger telescope and a dark country sky to bag this faint fuzzball, which astronomers expect to glow at 10th or 11th magnitude. Try to observe during the second or third week of September when the Moon is gone from the evening sky.

The comet will not be an easy target. Spotting it is like finding a specific tree when you’ve been dropped into the middle of a forest. Unless you’ve got a big scope, you likely won’t see the comet at low power. Bump up the magnification past 100x and slowly spiral out from the position marked on the finder chart. Motion helps your eye pick out a small, soft glow.

Although C/2011 F1 soon will disappear in the Sun’s glare, a recently discovered comet — C/2012 K5 (LINEAR) — should take its place this winter. That would satisfy us until spring, when we may see our first bright naked-eye comet in a few years. Astronomers expect C/2011 L4 (PanSTARRS) to reach at least 3rd or 4th magnitude when it comes into view in March and April 2013.

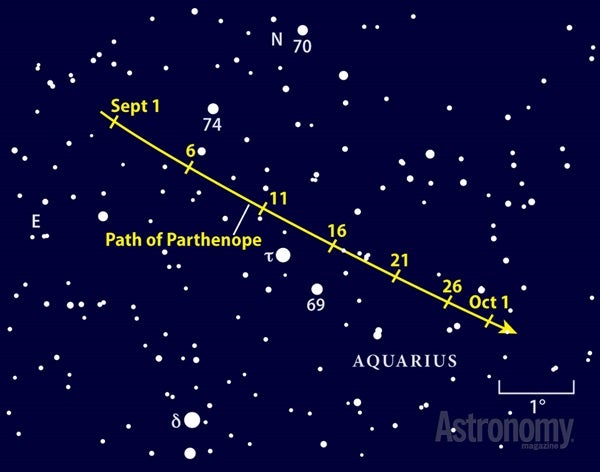

Ninth-magnitude Parthenope marches through southern Aquarius in September, passing within 1° of the moderately bright star Tau (τ) Aquaril at midmonth. Astronomy: Roen Kelly

Spy a mermaid swimming the autumn sky

The celestial embodiment of the mermaid Parthenope slides through the constellation Aquarius the Water-bearer during September. Glowing at 9th magnitude, the main-belt asteroid 11 Parthenope is bright enough to see easily through a 6-inch telescope from the suburbs or large binoculars from a dark-sky site. Wait until late evening for this region to climb higher in the sky. It’s also best to avoid the beginning and end of the month when a bright Moon lies nearby.

No conspicuous stars occupy southern Aquarius, but a pair of modest ones will get you to the asteroid’s vicinity. Delta (δ) Aquarii and Tau (τ) Aqr represent the stream of water running from Aquarius’ amphora into the mouth of Piscis Austrinus the Southern Fish. Parthenope passes within 1° of Tau in mid-September. Use the chart to pinpoint the asteroid, or sketch the field and return to the same area the next night; the object that moves is the space rock.

In January 2011, nearly 20 amateur astronomers timed Parthenope as it blocked the light of a background star. From these observations, astronomers determined that the asteroid is a potato-shaped rock 93 miles across its longest dimension.

Martin Ratcliffe provides professional planetarium development for Sky-Skan, Inc. Alister Ling is a meterologist for Environment Canada.