Currently, the only spacecraft orbiting our nearest planetary neighbor, Venus Express arrived at Venus on April 11, 2006. Since then, the spacecraft has gathered a wealth of data on the planet’s atmosphere and surface from its elliptical, 24-hour polar orbit.

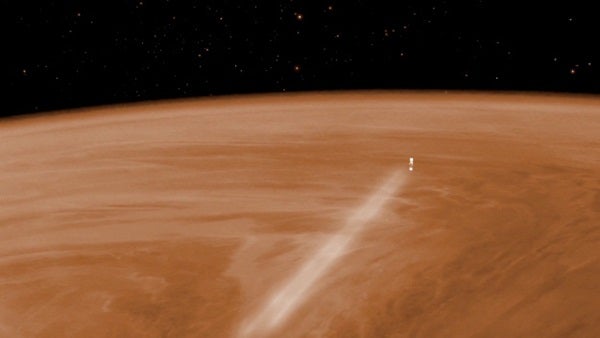

With the spacecraft’s fuel tank running low, the mission team decided to undertake several aerobraking campaigns, during which the orbiter would dip deeper than ever before into Venus’s atmosphere during each pericenter passage; pericenter is the point of closest approach in a spacecraft’s orbit around a planet.

By gradually reducing its pericenter altitude to around 81 miles (130 kilometers), the spacecraft would be able to provide unique, detailed, in-situ information about the sparse outer atmosphere, a region that is difficult to study using remote sensing instruments.

Aerobraking has been used for many decades as a fuel-efficient way to slow down a spacecraft in a controlled manner. It has been used by the Apollo Command Modules on their return from the Moon and by automated spacecraft arriving at Mars.

One of the major problems with aerobraking is that atmospheric friction places stresses on a spacecraft’s structure and causes its exterior to heat up rapidly. However, Venus Express was designed to survive modest aerobraking in case the initial orbit insertion did not work as planned. Fortunately, this backup procedure was never needed.

Now, near the end of its successful odyssey, the mission team had the opportunity to test and verify the spacecraft’s design and aerobraking procedures without risking the overall success of the mission. For the first time, an ESA spacecraft would deliberately dip deep into a planetary atmosphere and then rise to continue operations.

The aerobraking was performed near the lowest point of the orbit by turning the lower end of the spacecraft in the direction of travel and rotating the solar panels so that they created the most atmospheric drag.

Starting May 17, the pericenter altitude was allowed to slowly decrease naturally from 118 miles to 87 miles (190km to 140km). The orbit continued to alter under the influence of gravity, culminating in a month of “surfing” between 81 miles and 84 miles (131km and 135km) above the planet’s surface. Additional small thruster burns were used to lower the trajectory even further, reaching a minimum of 80 miles (129.2km) on July 11.

Although each dip into the atmosphere only slowed the orbiter’s speed by about 1 mile per second (1.6km per second), the combined effect of the daily drag at these lower altitudes was so great that its orbital period was eventually reduced from 24 hours to 22 hours, 20 minutes.

The campaign ended July 12, after which a series of 15 thruster burns raised the craft’s altitude again, placing it in a new orbit of 286 by 39,100 miles (460 by 63,000km).

“Below 155km [96 miles], the onboard accelerometers gave direct measurements of the rate of deceleration, which was directly proportional to the local atmospheric density,” said Håkan Svedhem from ESA.

“This provided an excellent way to study the overall density profile and small scale density variations during each dip into the atmosphere.

“To our surprise, we saw that the atmosphere appeared to be more variable than previously thought for this altitude, both from day-to-day and during each individual pericenter passage.”

The data indicate that the satellite experienced extreme heating cycles, with temperatures of the solar panels increasing to about 122° F (50° C) — a rise of more than 180° F (100° C) — during several of the brief sweeps through the atmosphere.

The atmosphere also became about 1,000 times denser between altitudes of 103 miles (165km) and 81 miles (130km), subjecting Venus Express to much higher forces and stress than during normal operations.

“We expected the density profile to be smooth,” said Svedhem, “but we saw wide variations, sometimes with a steep rise, flat top and steep decline, sometimes with several peaks or a triangular shape.

“One possible explanation is that we detected atmospheric waves. These features can be caused when high speed winds travel over mountain ranges. The waves then propagate upwards. However, such waves had never been detected at such heights — twice the altitude of the cloud deck that blankets Venus.”

At the time of the campaign, the low point of the orbit was located near the day-night terminator, at about 75° north latitude. Some marked changes were detected as Venus Express crossed the terminator.

“Atmospheric density changed very rapidly as the spacecraft moved from daylight into darkness,” said Svedhem. “It was about four times greater on the dayside than the nightside.”

Measurements of magnetic fields and energetic particles obtained during the campaign will be analyzed in the coming months and will certainly lead to new and improved models and a better understanding of the venusian atmosphere and its environment.

Having survived its dives into the atmosphere, Venus Express is continuing a program of more routine science observations. However, the intrepid orbiter is living on borrowed time.

“Since July, the pericenter of the orbit has been naturally decreasing again, and by the end of November, we shall attempt to raise it once again,” said Svedhem.

“Unfortunately, we do not know how much fuel remains in its tanks, but we are intending to continue the up-down process as long as possible, until the propellant runs out.

“We have yet to decide whether we shall simply continue until we lose control, allowing it to enter the atmosphere and burn up naturally, or whether we attempt a controlled descent until it breaks up.”

Either way, the tough little spacecraft will have revolutionized our knowledge of Earth’s mysterious, cloud-shrouded neighbor, sending back more data than all previous missions to Venus combined.