But the solar system offers plenty of brighter fare as well. Venus and Jupiter continue to dominate the early evening sky while Saturn climbs highest in the south before midnight. During the morning hours, Uranus and Neptune become tempting targets through binoculars. And finally, it’s worth taking a few minutes to view Mercury before sunrise in early July.

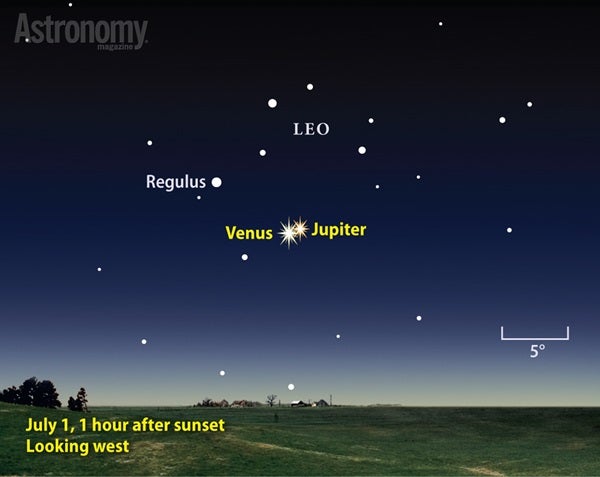

Anyone with a clear sky the evening of July 1 can’t help but notice Venus and Jupiter. The dazzling planets stand side by side in the west with just a Full Moon’s width between them. Venus shines at magnitude –4.6 and Jupiter at magnitude –1.8. Only the Full Moon itself — climbing higher in the southeastern sky this evening — appears brighter. (By the way, July brings the first “Blue Moon” — two Full Moons in a calendar month — since August 2012. July’s second Full Moon occurs on the 31st.)

As twilight descends, the two planets seem to grow more brilliant in contrast with the darker sky. They hover 8° to the lower right of 1st-magnitude Regulus, Leo the Lion’s brightest star, which forms the base of Leo’s Sickle asterism.

The planet pair remains visible for about two hours after the Sun sets in early July. During the next few weeks, Venus moves southwest (left as seen from mid-northern latitudes) of its companion. By the 9th, 4° separate the two. Venus then shines at magnitude –4.7, the peak brightness for its current evening reign.

The two planets and Regulus create an ever-changing triangle during July. On the 18th, a slender crescent Moon joins the scene to create a perfect picture opportunity. All four objects lie within a 6° circle, with our satellite less than 1° from Venus. And on the 23rd, both Venus and Jupiter appear 4° from Regulus. The trio sinks into bright twilight by the end of July, setting within an hour of the Sun.

Details in Jupiter’s atmosphere become harder to see in July as the planet sinks closer to the horizon. A lower altitude means its light passes through more of Earth’s turbulent air, reducing an image’s sharpness. The best views will come in late twilight, roughly 45 minutes after sunset, in the first half of the month.

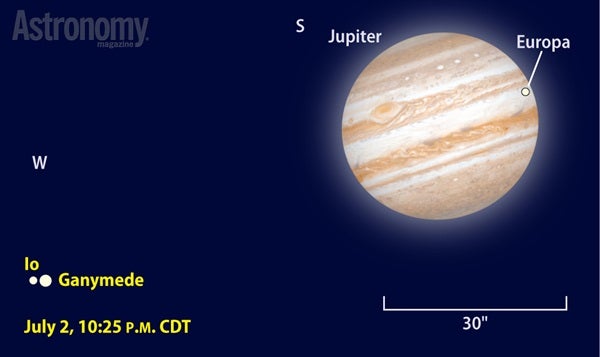

Tracking Jupiter’s four bright moons proves much easier. All orbit in the same plane, which currently tilts edge-on to both the Sun and Earth. This means the moons themselves can occult or eclipse one another. Although these so-called mutual events have been occurring since August 2014, the observing window is closing quickly. The last one comes in August, but by then Jupiter will be hopelessly lost in the Sun’s glare. This means early July is your last chance to witness one of these intriguing events until the satellite orbits align again in six years.

Perhaps the best such event for North American observers happens the evening of July 2. Starting at 10:29 p.m. CDT, Ganymede partially occults Io for four minutes. (Because of Jupiter’s limited visibility, only viewers in the Central and Mountain time zones can witness this event.)

Io returns the favor July 5 when it occults giant Ganymede for observers in western North America. The event begins at 10:18 p.m. MDT and lasts just two minutes. Two days later, on July 7, the same region sees Io occult Europa for five minutes commencing at 9:46 p.m. MDT.

Saturn stands roughly 30° above the southern horizon as darkness falls in July. The ringed planet shines at magnitude 0.3 at midmonth and is the brightest object in this part of the sky. It glows twice as bright as 1st-magnitude Antares, the luminary of the constellation Scorpius, which lies 13° southeast of the planet.

A telescope delivers spectacular views of Saturn and its rings. The planet’s disk appears 18″ across in mid-July while the ring system spans 40″ and tilts 24° to our line of sight. Any instrument should reveal the Cassini Division, a slim black gap that separates the outer A ring from the brighter B ring. Look carefully and you also might glimpse the gossamer-thin C ring close to the planet.

Saturn also rules over a family of modestly bright moons. Any telescope reveals 8th-magnitude Titan, the planet’s largest satellite. It passes due north of Saturn on July 6 and 22 and due south on the 13th and 29th. A 4-inch scope also reveals 10th-magnitude Tethys, Dione, and Rhea, which all orbit closer to Saturn than does Titan.

Each night these four moons change positions relative to one another and to Saturn. On July 5, look for Tethys and Dione just 7″ apart northwest of the planet, with Titan 1′ north of the pair and Rhea 44″ west of Tethys. On the 11th, Tethys, Dione, and Rhea form a straight line extending northeast from Saturn, with Titan well to their southeast.

The outermost bright moon is Iapetus, which takes 79 days to revolve around Saturn. It passes 2.2′ south of the planet July 16 and spends the rest of the month heading toward a greatest western elongation in early August. Whenever Iapetus lies well west of the ringed world, its brighter hemisphere faces Earth and it glows at 10th magnitude. When the moon is far east of the planet, as it is in early July, it appears just one-fifth as bright. You should be able to track Iapetus’ growing brightness if you follow it all month.

People will long remember July 2015 as the month when humans got their first close-up look at Pluto. The New Horizons spacecraft flies past the distant world July 14 and should be returning extraordinary views to eager scientists all month. By a stroke of luck, Pluto also reaches opposition and peak visibility this month. Observers with 8-inch or larger telescopes can track down the 14th-magnitude point of light. For viewing tips and detailed finder charts, see “Hunt the last planet” on p. 46.

Neptune rises shortly before midnight local daylight time and climbs highest in the south as twilight begins. You can find the magnitude 7.8 planet through binoculars among the background stars of Aquarius the Water-bearer. Use 4th-magnitude Lambda (λ) Aquarii as your guide. Neptune begins July 2.1° southwest of the star; the gap grows to 2.6° by month’s end. Through a telescope at moderate magnification, the planet shows a blue-gray disk that spans 2.3″.

Although it lies just one constellation east of Neptune, Uranus doesn’t clear the eastern horizon until around 2 a.m. local daylight time in early July. (It rises two hours earlier by month’s end.) Glowing at magnitude 5.8 against the backdrop of Pisces the Fish, it is quite easy to spot through binoculars. Uranus spends the month within 0.6° of 5th-magnitude Zeta (ζ) Piscium and is the brightest object southwest of this star. A telescope reveals the planet’s 3.5″-diameter disk and distinctive blue-green hue.

Mercury shines brightly in morning twilight during July’s first two weeks. On the 1st, it glows at magnitude –0.2 and stands 8° high in the east-northeast a half-hour before sunrise. A telescope shows a disk 7″ across and just over half-lit. The inner world mostly maintains this altitude each morning during July’s first week while brightening about 0.1 magnitude each day. On the 7th, it appears 6″ in diameter and the Sun illuminates 70 percent of its disk. Mercury dips deeper into the twilight and becomes harder to see in the following week. It passes behind the Sun from our viewpoint July 23.

Mars remains lost in the Sun’s glare throughout July. It will return to view before dawn in late August.

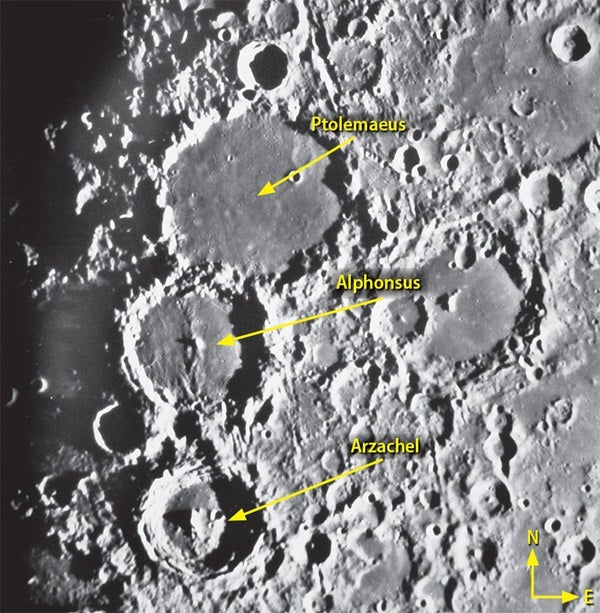

The Moon is a world unto itself, but humans have dressed its face with an honor roll of great scientists and philosophers in Earth’s history. Generally speaking, the bigger the name, the more impressive the feature, with the most striking reserved for those luminaries of the pre-telescope age.

But the great Italian scientist Galileo Galilei must have rubbed lunar cartographers the wrong way because “his” crater (Galilaei) is only half the size and much less prominent than the one named for his friend and student, Vincentio Reinieri (Reiner). Appropriately, the two craters appear near each other in the large western “sea” named Oceanus Procellarum. Look for them due west of Copernicus, the dominant large crater with the prominent rays just north of the lunar equator.

Galilaei spans 10 miles and shows a sharp rim. It formed well after the heavy bombardment and huge lava floods that characterized the earlier parts of the Moon’s history. Reiner lies to its neighbor’s southeast and appears equally fresh.

As evening arrives in North America on July 28, the waxing gibbous Moon stands high in the south. The lunar terminator — the line dividing day from night on the Moon — then cuts right through Galilaei about 10° north of the lunar equator. If light from the bright disk bothers your eyes, use a dark filter to reduce the glare or pump up the magnification to spread out the light and reduce its intensity.

The best overview of the region comes the following evening (July 29) when the scene closely matches the photo above. The Sun then lies higher in the lunar sky, so especially reflective features can catch the eye. Look for a curious white feature, Reiner Gamma, between Galilaei and Reiner. Observations during the Apollo missions confirmed that this is not a topographic feature but, similar to other white splotches on the farside, is highly magnetic. Lunar scientists have yet to reach a consensus as to what Reiner Gamma is or how it formed.

July features several meteor showers, though none rises to major status. The Piscis Austrinids and Alpha Capricornids each deliver a maximum of five meteors per hour at their late July peaks, though Southern Hemisphere observers have better views.

The month’s best performer is the Southern Delta Aquariid shower, which typically produces 15 to 20 meteors per hour. Unfortunately, it peaks the morning of July 30, just one day before the month’s second Full Moon. The shower does maintain its peak level for several days, however, so you’ll likely get a better show if you watch in the hour or two between moonset and the start of morning twilight July 27 and 28.

| WHEN TO VIEW THE PLANETS |

||

| Evening Sky |

Midnight | Morning Sky |

| Venus (west) |

Saturn (southwest) |

Mercury (northeast) |

| Jupiter (west) |

Neptune (southeast) |

Uranus (southeast) |

| Saturn (south) |

Neptune (south) |

|

| |

|

|

| |

||

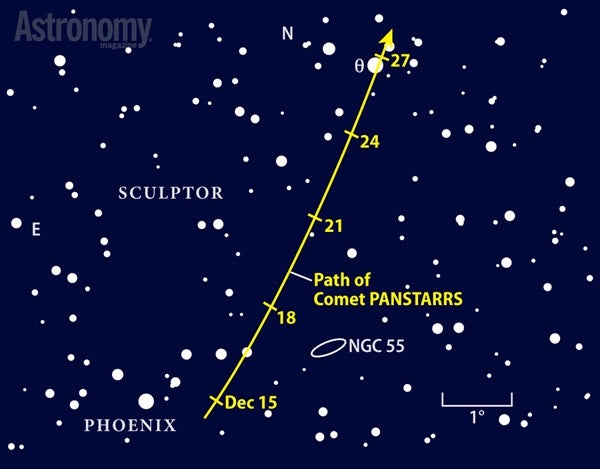

The comet drought of the past few months is coming to an end. Although none of July’s icy visitors reach naked-eye visibility, telescope owners could get some nice views. Observers on each side of the equator have something to follow this month. To the south, Comet Catalina (C/2013 US10) should glow around 8th magnitude as it flies with the birds in Phoenix, Grus, and Tucana. Astronomers hope this comet will be a nice binocular object — and perhaps become visible to the naked eye — for northern observers in December and January.

In the Northern Hemisphere, the fainter but fascinating Comet 141P/Machholz beckons. Ever since Don Machholz discovered it in 1994, this loosely packed ice ball has been breaking up and flaring. Of the five original components, only two came back in 2000 and just one was seen in 2005. The comet hid behind the Sun at its 2010 return, so no one observed it. Will there be anything left this time, or will we witness a spectacular final breakup?

During July, Machholz covers a large strip of sky from Pisces to Perseus. Visual observers should wait until New Moon on July 15/16 and use an 8-inch or larger instrument to hunt for the comet before dawn. It then lies near 4th-magnitude Gamma (γ) Trianguli and 10th-magnitude spiral galaxy NGC 925. An even closer celestial encounter occurs July 26 and 27 when the comet slides through the northern part of the California Nebula (NGC 1499).

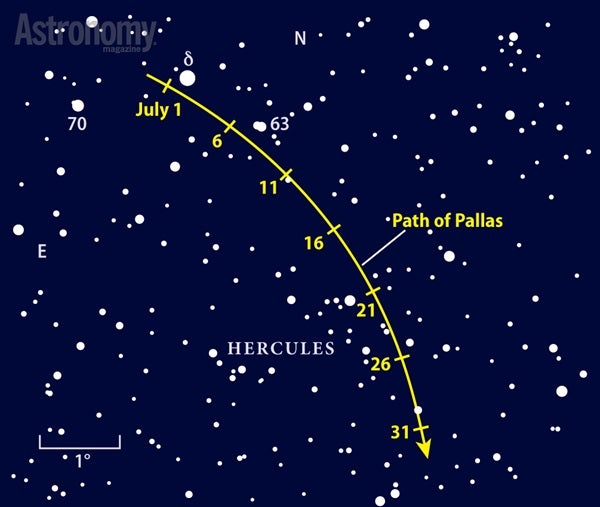

If you can make out Hercules the Strongman in July’s late evening sky, you should have little problem pegging asteroid 2 Pallas. It doesn’t get much easier than on July 1 and 2, when the space rock passes within 0.3° of 3rd-magnitude Delta (δ) Herculis, the constellation’s third-brightest star.

The finder chart below should help you pick out Pallas on other nights. If you can’t identify the asteroid quickly, a surefire way is to watch it move from night to night. Sketch the four or five dots closest to the asteroid’s marked position, and then return a night or two later. The “star” that moved is Pallas. Many seasoned observers use this method so they can be sure they haven’t spotted a background star near Pallas’ brightness. (The 325-mile-wide asteroid dims from magnitude 9.5 to 9.8 this month.) On July 11, 20, and 30, Pallas passes close enough to a field star that it shifts position noticeably in just four or five hours.

Unlike the planets and most main-belt asteroids, Pallas’ orbit inclines steeply to the plane of the solar system. Notice how far north it is now — placing it in prime position for Northern Hemisphere observers — by comparing its position with Saturn some 40° to the south.

Martin Ratcliffe provides planetarium development for Sky-Skan, Inc. from his home in Wichita, Kansas. Meteorologist Alister Ling works for Environment Canada in Edmonton, Alberta.