Mars grows markedly brighter in January as it approaches opposition and peak visibility in early March. This biennial event always sparks interest among backyard observers. Once Mars climbs high in the south during the predawn hours, Saturn joins the show in the southeast. Not to be left out, Mercury makes a fleeting appearance in the morning sky during January’s first week. Finally, keep an eye out for Quadrantid meteors before dawn January 4. If the weather cooperates, observers should catch a great show.

Let’s begin our tour in the western sky after sunset. The first point of light you’ll see as darkness descends is brilliant Venus. The month begins with the planet situated in central Capricornus. Although the dim stars of the Sea Goat barely show up an hour after sundown, Venus dazzles. The planet shines at magnitude –4.0 and is sure to draw the attention of even casual observers.

During January, Venus’ angular separation from the Sun grows from 34° to 40°. This may not sound like much, but it has a striking effect. On the 31st, Venus sets more than an hour later than it did when the month began and more than 3 hours after sunset.

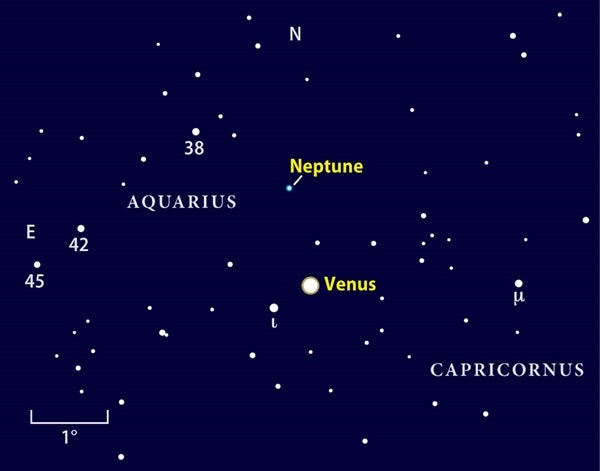

From night to night, Venus moves steadily eastward relative to the background stars. It leaves Capricornus January 11 and enters neighboring Aquarius the Water-bearer. The next evening, it has a close encounter with Neptune. The distant planet glows at magnitude 8.0, so you’ll need binoculars or a telescope to spot it. Once the sky grows dark, center Venus in the field of view and then hunt for Neptune 1.2° to its north. You also will see 4th-magnitude Iota (ι) Aquarii just 0.5° (the width of a Full Moon) southeast of Venus. Neptune sinks into the twilight glow as January progresses and will disappear by month’s end. It will be in conjunction with the Sun in mid-February.

The view of Venus through a telescope changes slowly during January. As the planet swings around the Sun and heads toward Earth, its size grows and its phase wanes. This month, Venus’ apparent diameter swells from 13″ to 15″ while its phase diminishes from 83 percent to 75 percent lit. The rate of these changes will increase dramatically in the coming months.

Head one constellation northeast of Aquarius and its residents, Venus and Neptune, and you’ll land on Pisces with its temporary tenant, Uranus. This planet lies in the southern part of the Fish and stands about halfway from the southwestern horizon to the zenith as soon as the sky grows dark. Uranus shines at magnitude 5.9, bright enough to see with naked eyes under a dark sky but a far easier target through binoculars.

The waxing crescent Moon provides a convenient guide to the planet’s location January 27. That evening, our nearest celestial neighbor passes 6° to Uranus’ north (to the upper right from mid-northern latitudes). On any other clear night, use Pisces’ Circlet asterism as a guide. The planet lies approximately 10° east-southeast of

the center of this five-star oval group. To confirm a sighting of Uranus, center it in your telescope’s field of view and use a medium-magnification eyepiece. The planet will show a 3.4″-diameter disk with a distinctive blue-green color.

You can’t miss Jupiter if you look skyward on any clear January night. The giant planet appears some 60° above the southern horizon at nightfall and shines at magnitude –2.5. Its high altitude distinguishes it from Venus, which is the only other point of light that glows so brightly.

Each night, the planet appears to swing toward the western horizon as Earth rotates from west to east under the starry canopy. This motion causes Jupiter to set about 4 minutes earlier each night. Still, it remains visible until past midnight local time throughout January.

Jupiter shows off its spectacularly detailed atmosphere to anyone who points a telescope at it. Although the planet’s diameter shrinks from 43″ to 39″ during January, even at its smallest, it appears more than twice as big as any other planet. And it’s plenty large enough to reveal the major belts and zones that run parallel to the jovian equator. On nights with steady seeing, look for finer details within these belts and zones. The best views will come in early evening when the planet lies higher in the sky.

Any telescope will show as many as four moons near Jupiter. Io, Europa, and Ganymede — the innermost of these so-called Galilean moons — disappear whenever they pass behind the planet or into its shadow. When these three cross in front of Jupiter, observers can see their disks and their ink-black shadows against the bright jovian cloud tops. Callisto lies far enough from the planet that it passes above and below both the disk and shadow, so it’s always on view. North American observers can find this outer moon due north of Jupiter the evening of January 21.

Shadow transits probably rank as the most enticing of these satellite events. Because Io circles the planet fastest, completing an orbit in just 1.8 days, it experiences the most. North American observers can watch for this moon’s black shadow beginning a few minutes after the following start times: January 4 at 11:07 p.m. EST, January 13 at 7:32 p.m., January 20 at 9:28 p.m., and January 27 at 11:24 p.m. Each Io shadow transit lasts a little longer than 2 hours.

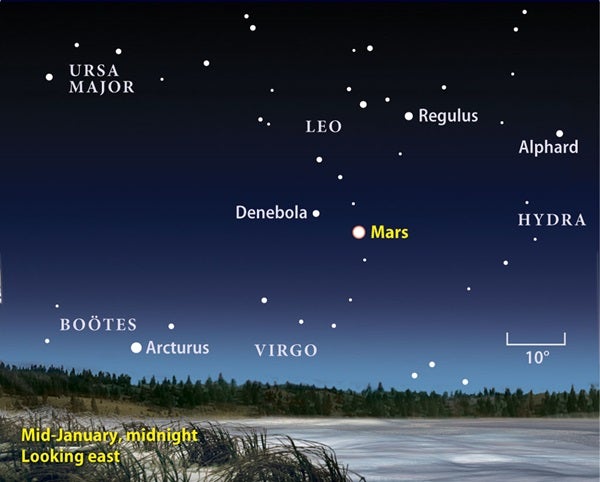

Oddly enough, the changes to its physical appearance don’t translate into significant motion in the sky. Mars starts January against the backdrop of southeastern Leo the Lion. It moves slowly to the east, crossing into Virgo the Maiden January 14. Its eastward motion comes to a halt January 24, and the Red Planet then reverses direction. It will reenter the Lion’s friendly confines in February’s first week. Mars rises after 10 p.m. local time January 1 and nearly 2 hours earlier by month’s end.

Experienced observers know Mars needs to be 10″ across before it shows significant detail through a telescope. So, January affords our first decent look in about 2 years. For the best views, wait until the planet rides high in the sky between about 2 a.m. and dawn. A lofty perch means the planet’s light traverses less of Earth’s image-distorting atmosphere. The first feature you’ll see on the disk will be the white north polar cap. Extended viewing under favorable conditions will reveal dusky markings scattered across the surface.

Saturn rises before 1 a.m. local time in mid-January and appears nearly halfway up the southern sky by the time dawn breaks. The ringed planet lies in south-central Virgo, some 7° east-northeast of that constellation’s brightest star, Spica. Saturn shines at magnitude 0.7, slightly but noticeably brighter than the star. A Last Quarter Moon lies below this pair the morning of January 16.

Any telescope reveals Saturn’s 17″-wide disk surrounded by a glorious ring system that spans 39″. The rings currently tilt 15° to our line of sight, so details within them stand out. Look for the Cassini Division, a nearly 3,000-mile-wide gap that separates the outer A ring from the brighter B ring. On mornings with excellent seeing, you might glimpse the much thinner Encke Division near the A ring’s outer edge.

Innermost Mercury shines at magnitude –0.4 on New Year’s morning. It then rises 90 minutes before the Sun and appears 9° above the southeastern horizon a half-hour before sunrise. Don’t confuse it with the ruddy glow from magnitude 1.1 Antares, which rises approximately 30 minutes before Mercury and lies 11° to its upper right. The planet appears noticeably brighter than the star. If you can’t spot the pair with naked eyes, binoculars will help you see them in the twilight glow. A view through a telescope shows the planet’s 5.7″-diameter gibbous disk. Mercury sinks toward the horizon with each passing morning and will disappear by the middle of the month.

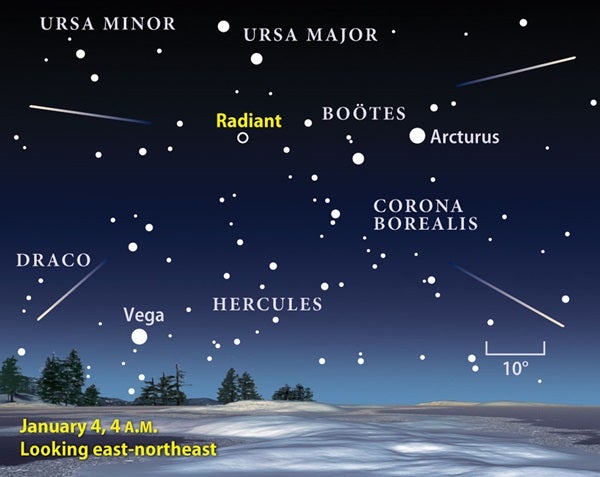

The Quadrantid meteor shower reaches its peak the morning of January 4. Although a waxing gibbous Moon will drown out fainter members for much of the night, it sets shortly after 3 a.m. local time, leaving nearly 3 hours to observe under a dark sky. Bad weather can be a problem at this time of year, but those who brave the cold might see a memorable event.

The shower’s peak averages about 120 meteors per hour, but it can produce anywhere from 60 to 200. This range may derive more from the clouds that often plague winter observing, however, than from true variations in the shower. Quadrantid meteors appear to radiate from a point in northern Boötes. Their name originates from the now-defunct constellation Quadrans Muralis, which formerly occupied this region.

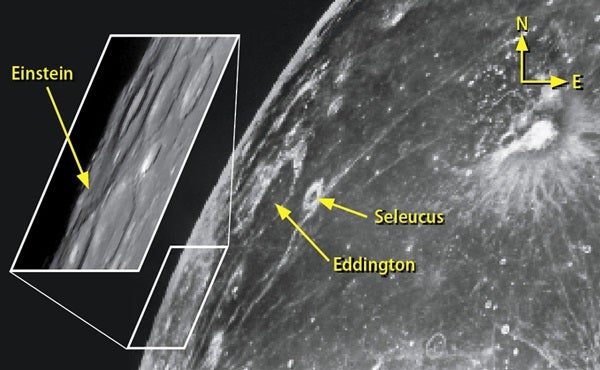

Thanks to favorable orbital geometry, lunar observers can stroll along the distant shoreline of Oceanus Procellarum (Ocean of Storms) during January. The western border of this giant lava-filled depression lies in the Moon’s northwestern quadrant, not far from the lunar limb (edge). This region often tilts away from Earth or comes into view only after midnight, but this month the white highlands appear for a whole week starting a day or two before the Full Moon of January 9.

On the evening of the 7th, look for the prominent crater Seleucus. A bright ridge extends south from this 27-mile-wide feature, which lies nearly due west of brilliant Aristarchus. Just west of Seleucus and near the terminator that separates lunar day from night sits the horseshoe-shaped crater Eddington. A sea of now-hardened lava has buried the southern half of this 78-mile-wide crater.

January 8 is a perfect evening to identify Einstein. This crater spans 105 miles and lies west and a little south of Eddington. Subsequent impacts have battered Einstein over the eons; the result of one such blast created a 28-mile-diameter crater at its center. The Moon’s apparent tilt, known as libration and caused by our satellite’s changing orbital speed, couples with the low Sun angle to make every bump in this region stand out.

From Full Moon on the 9th to just past midmonth, look for the many bright specks that mark the locations of small craters. If the Moon appears too bright, use a filter to cut the glare. A polarizing filter works well because you can dial in the amount of reduction.

| When to view the planets | ||

| EVENING SKY | MIDNIGHT | MORNING SKY |

| Venus (southwest) | Mars (east) | Mercury (southeast) |

| Jupiter (south) | Jupiter (west) | Mars (southwest) |

| Uranus (southwest) | Saturn (south) | |

| Neptune (southwest) | ||

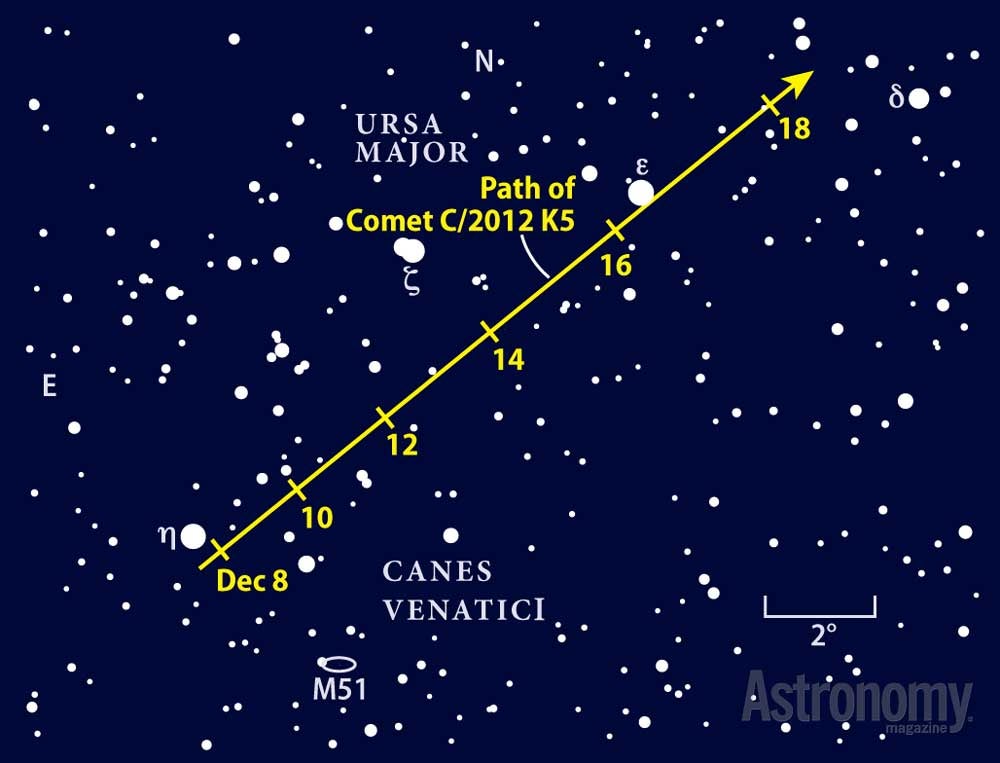

Comet P/2006 T1 (Levy) has been brightening rapidly during the past few months and should reach 7th or 8th magnitude in January. Discovered October 2, 2006, by Astronomy columnist David H. Levy, this comet takes slightly longer than 5 years to orbit the Sun on a track that brings it from Earth’s neighborhood out to Jupiter’s.

Comet P/2006 T1 moves quickly across the evening sky during January, starting in Pegasus and traversing both Pisces and Cetus before winding up in Eridanus. You’ll want to mark your calendar for the nights of December 31 through January 2, when observers may witness the rare sight of an anti-tail. These tails point toward the Sun instead of away like normal ones do, a trick of perspective we get when viewing the comet’s fan-shaped outflow edge-on. As an added treat during this period, the comet lies within a few degrees of Algenib, the 3rd-magnitude star that marks the southeastern corner of the Great Square of Pegasus.

Once the Moon moves out of the early evening sky around January 10, look for Levy some 10° west of brilliant Jupiter. The comet slides south of the giant planet during the next several nights. The finder chart at right doesn’t include Jupiter because its own motion would clutter the field.

When viewed at moderate magnification, the comet’s ion tail should end abruptly on its southeastern flank as the solar wind sculpts its leading edge. Compare this view with the southwestern side, where the trailing dust tail spreads out diffusely.

And don’t forget about Comet C/2009 P1 (Garradd). It rises in the early morning hours and reaches a decent altitude before dawn. Glowing around 6th magnitude, Garradd lies in the constellation Hercules, about two binocular fields to the upper right of Vega.

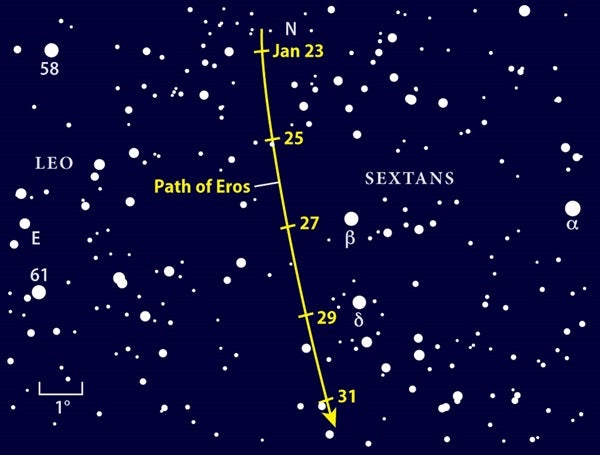

Asteroid 433 Eros comes to opposition every 2 to 3 years. Normally, this doesn’t generate news because Eros rarely brightens above 10th magnitude. But once in a while, it comes close enough to Earth to show up through small telescopes. The last time this happened was 1975. It happens again in January when it reaches magnitude 8.5.

Eros measures only 7 miles across and 21 miles tip to tip, so it has to come really close to Earth to get on observers’ radar screens. It pulls within 16.6 million miles at closest approach on the 31st.

Eros begins the month in Leo, northeast of that constellation’s Sickle asterism. It then heads south into the less familiar neighborhood of Sextans. Wait to observe until late evening, once this region has climbed fairly high in the east. If you want to gaze upon the space rock named for the Greek goddess of love, avoid the times when the Moon is in the sky like a big pizza pie, from January 10 to 13.

Eros moves fast enough that you can detect its motion within an hour, which makes it easy to identify. Unfortunately, speed has its disadvantages. The asteroid covers so much sky that we can’t show it all month; the chart depicts it during its brightest phase in late January.

Martin Ratcliffe provides professional planetarium development for Sky-Skan, Inc. Alister Ling is a meterologist for Environment Canada.