Let’s start our tour of the sky in the west shortly after darkness falls. Uranus lies 30° east of the Sun as March begins, so it hangs low in the evening sky. From mid-northern latitudes on the 1st, the planet stands about 10° above the horizon once twilight fades away.

If you have a clear western horizon, grab your binoculars and try to spot the magnitude 5.9 planet. Use Epsilon (ε) and Delta (δ) Piscium as guides. These two 4th-magnitude stars lie 3.5° apart; Uranus stands 4.5° south-southwest of (below) Delta. The planet disappears into the twilight glow by mid-March.

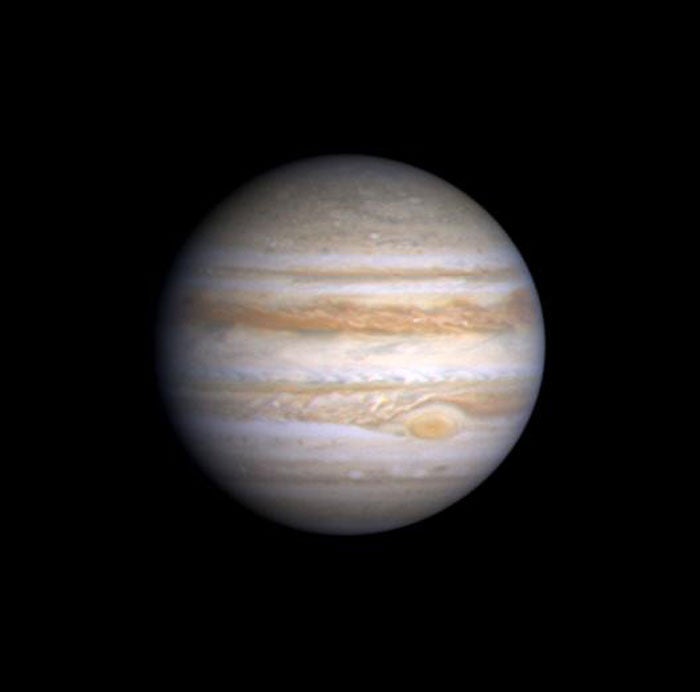

You don’t need to wait for total darkness to view the other early evening planet. Jupiter appears brilliant among the background stars of Gemini and lies nearly overhead during twilight. Because the giant planet is well north of the celestial equator, it doesn’t set until nearly 4 a.m. Jupiter shines at magnitude –2.3 at midmonth, 25 times brighter than the Twins’ brightest star, Pollux.

When viewed through a telescope, Jupiter is one of the finest sights in the heavens. Although its disk has slimmed more than 10 percent since its early January peak, it remains large (41″ across in mid-March) and shows superb detail. The sharpest images should come in early evening when the planet lies highest in the sky.

Look for an alternating series of bright zones and darker belts running parallel to Jupiter’s equator. You’ll almost always see two belts, but several more pop into view during moments of good seeing. The Great Red Spot shows up approximately half the time — whenever the planet’s rotation carries it onto the Earth-facing hemisphere.

Jupiter’s four bright moons orbit their home world quickly enough that their positions change noticeably from night to night and often hour to hour. You typically will find at least one moon on each side of the planet, but rarely all four line up on one side. March 8 provides one such opportunity. Observers in eastern North America can catch them in the correct order, too, with Io closest to Jupiter followed by Europa, Ganymede, and Callisto. Within an hour after sunset, Ganymede and Europa swap positions.

But the moons put on their best show when they cast their dark shadows onto the jovian cloud tops. The finest such transit in March occurs on the 23rd when the shadows of both Io and Ganymede appear on the planet’s disk at the same time. An hour after the Sun sets across central North America (it is already dark in the east), Io’s shadow lies halfway across Jupiter. Io and Ganymede themselves stand 11″ apart just off the planet’s western limb.

An hour later, as Io’s shadow prepares to lift back into space, Ganymede’s larger shadow shows up on the opposite limb. Both shadows remain on the disk between 10:09 and 10:32 p.m. EDT. Ganymede’s shadow leaves the disk about three hours later, at 1:26 a.m. EDT on the 24th. Pay attention to the relative separation between the moons and their shadows. Because the Sun illuminates the system from well west of our line of sight and Ganymede lies much farther from Jupiter than Io, the moons dwell near each other while their shadows appear far apart. It is a great illustration of the 3-D nature of the jovian system.

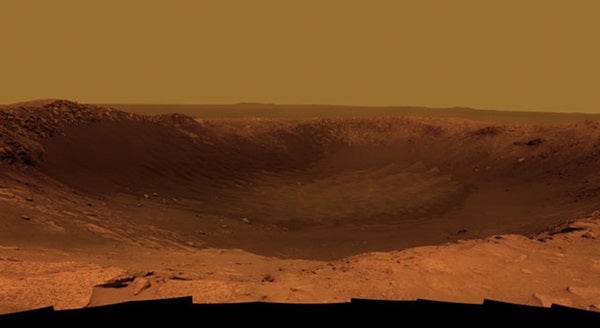

Whenever Jupiter is visible in the night sky, it shines brightly and looks impressive through a telescope. Mars, on the other hand, rarely appears either bright or impressive. But for a few months every two years or so, the Red Planet morphs into a remarkable object that captures the attention of both casual naked-eye viewers and dedicated telescopic observers. That time has arrived.

Mars appears conspicuous throughout March, but it grows more prominent with each passing day. It rises around 9:30 p.m. local time early this month and during twilight by month’s end. The Red Planet’s brightness more than doubles in March, growing from magnitude –0.5 to –1.3, while the diameter of its disk swells by 25 percent, from 12″ to 15″. It will grow only another 0.5″ by the time it peaks in April.

Mars becomes stationary against the stars of Virgo on March 1, some 6° northeast of the constellation’s brightest star, Spica. The planet then starts trekking westward, reaching a point 5° due north of the star on the 31st. Notice the color difference between orangish Mars and bluish Spica. The contrast really stands out through binoculars.

The view through a telescope improves as the night goes on and the planet climbs higher. It reaches its peak around 3 a.m. local daylight time at midmonth when it lies about halfway between the southern horizon and the point directly overhead. The greater altitude means the planet’s light travels through less of Earth’s turbulent atmosphere, providing sharper images of the martian disk.

Mars’ most conspicuous feature is its north polar cap. This bright white spot is well-positioned because the planet’s north pole tips about 20° in our direction. The polar cap is shrinking as summer tightens its grip on that world’s northern hemisphere, but it will remain prominent for several months.

The planet’s most recognizable dark feature is Syrtis Major. This dusky region lies just north of Mars’ equator and shows up best in March’s fourth week when it lies near the center of the planet’s disk around midnight EDT.

Saturn rises a little more than two hours after Mars. The ringed planet lies in Libra and reaches its maximum altitude shortly before morning twilight commences. Saturn shines at magnitude 0.4, more than two magnitudes brighter than any of Libra’s stars.

Even small telescopes deliver impressive views of Saturn. This month, the planet’s disk appears 18″ across while the rings span 40″ and tilt 23° to our line of sight. Saturn will grow bigger and shine brighter as its May 10 opposition approaches.

Modest telescopes can show you several of the ringed world’s moons. Any instrument reveals 8th-magnitude Titan, but you’ll likely need a 4-inch scope to spot the 10th-magnitude trio of Tethys, Dione, and Rhea. Titan’s 16-day orbit brings it due south of Saturn on March 6 and 22 and due north March 15 and 31. The other three satellites all orbit Saturn in less than five days, so they typically change positions noticeably in a few hours.

Mercury and Venus both reach the peaks of their morning apparitions this month. Unfortunately, neither planet climbs high. The ecliptic — the apparent path of the Sun across the sky — makes a shallow angle to the eastern horizon before dawn in early spring. This means angular separation from the Sun translates more into distance along the horizon than altitude above it.

Venus fares far better than its inner neighbor, however. At greatest elongation on the 22nd, it lies 47° west of the Sun. It then rises two hours before our star and stands 15° high a half-hour before sunrise. But its brilliance is what sets it apart. Shining at magnitude –4.5, it appears more than two magnitudes brighter than Jupiter, the sky’s second-brightest point of light. Five days after greatest elongation, on March 27, a crescent Moon passes 4° north of Venus.

Those who target the inner world through a telescope won’t be disappointed. The period around greatest elongation is always a good one for seeing rapid changes. On March 1, the planet spans 33″ and the Sun illuminates 36 percent of its disk. By the 31st, Venus’ diameter has shrunk to 22″ while its phase has waxed to 54 percent lit.

Mercury reaches greatest western elongation before dawn March 14. Although 28° separate it from the Sun, it appears only 5° high 30 minutes before sunrise. The planet shines at magnitude 0.1, bright enough to see through binoculars against the twilight glow.

A CRESCENT MOON EXTRAVAGANZA

Moon-watchers love the early spring. The ecliptic rises almost vertically from the western horizon after sunset, which places the waxing crescent Moon higher in the evening sky than at other times of the year. The favorable geometry also aligns the crescent parallel to the horizon, giving it the look of the Cheshire Cat’s smile.

Although a few experienced observers on the West Coast might spy the 18- or 19-hour-old lunar sliver on March’s first night, most skywatchers will get their first peek on the 2nd. Earthshine — sunlight reflecting off our planet to the Moon and back again — should be prominent. Take a few minutes to pick out some Full Moon features on the dimly lit “dark side.” Tycho’s rays, brilliant Aristarchus, and several maria should be easy to see. In contrast, the jumble of bright and dark crater arcs on the lit crescent will be challenging to identify.

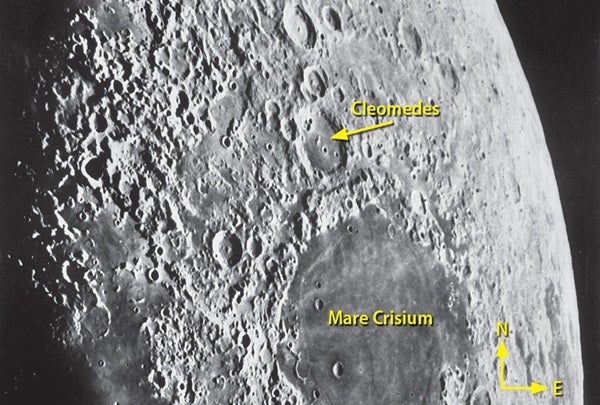

A significantly fatter crescent sits noticeably higher in the March 3 sky. Several recognizable landmarks dot the Moon’s lit face this evening. In the north, half of Mare Crisium (the Sea of Crises) appears lit. Frozen lava covers the floor of this giant basin, and a ring of tall mountains surrounds it. In contrast to its name, Crisium’s floor appears relatively tranquil. The shallow Sun angle highlights a wrinkle ridge near the sea’s eastern shore. This feature formed when lava solidified billions of years ago and the ground subsided.

By March 4, all of Crisium lies in sunlight. Pump up your scope’s magnification to find the smaller craters on the mare’s floor; these will disappear under the higher Sun in a day or two. Next, look a bit north of Crisium for the crater Cleomedes. The lava-covered floor of this 78-mile-wide impact feature sports two fairly prominent craters measuring about 7 miles across. Cleomedes’ inconspicuous central peak appears slightly off-center. Kick up the power again to look for Rima Cleomedes, a long, thin rille in the crater’s northern half. Be patient for moments of good seeing, when the turbulent atmosphere above your head steadies.

SPRING’S SUBTLE GLOW

While meteors are few and far between during March, the end of the month offers observers a great chance to see the zodiacal light. This ethereal glow — caused by sunlight reflecting off trillions of dust particles in the plane of the solar system (the ecliptic) — shows up best in early spring when the ecliptic makes a steep angle to the western horizon after sunset. Once the Moon leaves the evening sky around March 18, you’ll have about two weeks to see the light.

The cone-shaped glow shines about as bright as the Milky Way, so you’ll need a dark site to find it. Wait until twilight fades away completely; then scan back and forth above the western horizon with just your naked eyes. Under excellent conditions, people with good eyesight can trace the pyramid of light 50° into Taurus the Bull.

| WHEN TO VIEW THE PLANETS |

||

| Evening Sky |

Midnight | Morning Sky |

| Jupiter (south) |

Mars (southeast) |

Mercury (east) |

| Uranus (west) |

Jupiter (west) |

Venus (southeast) |

| |

Saturn (southeast) |

Mars (southwest) |

| Saturn (south) |

||

| Neptune (east) |

||

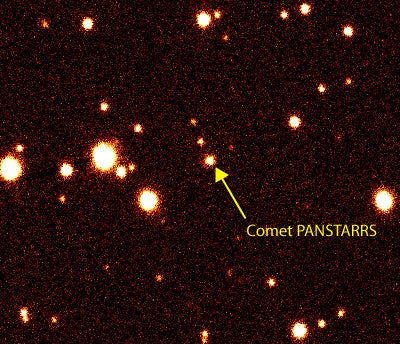

SAY HELLO TO ANOTHER PANSTARRS COMET

The sky is awash with comets named after the Panoramic Survey Telescope & Rapid Response System (Pan-STARRS) located on Haleakala in Hawaii. This 1.8-meter telescope is one of the world’s most prolific comet-hunting machines. Barring some new discovery, 2014’s brightest ball of ice and dust should be another Comet PANSTARRS: C/2012 K1.

Astronomers expect this cosmic interloper to become a decent binocular target by late summer. In March, however, it glows around 10th magnitude and appears as a puff of reflected sunlight. Under a dark sky, you’ll need a 4-inch telescope to track down this visitor. You should use an 8-inch or larger instrument if you plan to view from a suburban backyard.

As March opens, look for PANSTARRS before dawn as it glides in front of the celestial strongman, Hercules. The comet is an easy 1.5° hop southeast of 3rd-magnitude Beta (β) Herculis. Three mornings later, PANSTARRS passes 0.9° due east of the star. While you’re in the vicinity, slew another 3° east to catch the Turtle Nebula (NGC 6210). This well-defined greenish disk is a planetary nebula, the puffed-off outer layers of a dying star lit up by the ultrahot stellar remnant.

After mid-March, the comet crosses into Corona Borealis. It lies within 1° of 5th-magnitude Rho (ρ) Coronae Borealis on the month’s final three days. By then, this region rises during the evening hours, though it is still highest before dawn.

PALLAS SNAKES ITS WAY ACROSS HYDRA

The moderately elongated and highly inclined orbit of asteroid 2 Pallas means it doesn’t grow bright very often. It shines at magnitude 7.0 in early March, the same as it did at opposition in late February. Pallas hasn’t been this bright since 1991 and won’t achieve a similar magnitude again until 2028.

The main-belt asteroid spends March trolling the celestial waters of Hydra the Water Snake. This region lies highest in the south during late evening. On March 1, Pallas passes 3° east of Hydra’s brightest star, 2nd-magnitude Alphard. The asteroid heads nearly due north from there, a reflection of its high-inclination orbit.

Although Pallas appears relatively bright, it has to compete with the many background stars that lace the outer edges of the winter Milky Way. Use the chart below to hop to the space rock’s position. Avoid the nights of March 11 to 15 when the bright Moon lies nearby.

German astronomer Heinrich Olbers discovered Pallas in March 1802, less than 15 months after Giuseppe Piazzi spotted the first asteroid, Ceres. With a diameter of 325 miles, Pallas also ranks second in size to Ceres among the asteroids.

Martin Ratcliffe provides planetarium development for Sky-Skan, Inc. from his home in Wichita, Kansas. Meteorologist Alister Ling works for Environment Canada in Edmonton, Alberta.