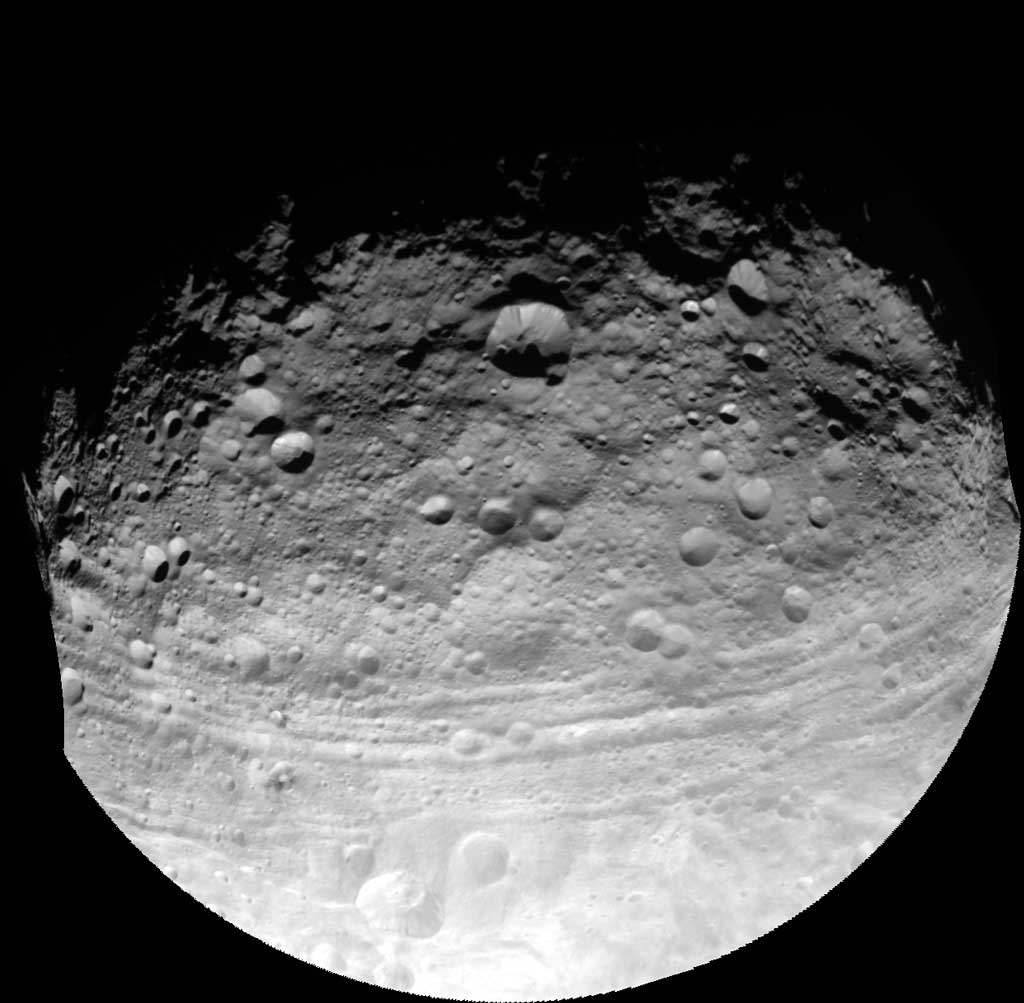

Asteroid surface deformities are typically straightforward cracks formed by crashes with other asteroids. Instead, an extensive system of troughs encircles Vesta, the second most massive asteroid in the solar system, about one-seventh as wide as the Moon. The biggest of those troughs, named Divalia Fossa, surpasses the size of the Grand Canyon by spanning 289 miles (465 kilometers) long, 13.6 miles (22km) wide, and 3 miles (5km) deep.

The origin of these troughs on Vesta has puzzled scientists. The complexity of their formation can’t be explained by simple collisions. New measurements of Vesta’s topography, derived from images of Vesta taken by NASA’s Dawn spacecraft last year, indicate that a large collision could have created the asteroid’s troughs. But this only would have been possible if the asteroid is differentiated — meaning that it has a core, mantle, and crust — said Debra Buczkowski of the Johns Hopkins University Applied Physics Laboratory in Laurel, Maryland. Because Vesta is differentiated, its layers have different densities, which react differently to the force from the impact and make it possible for the faulted surface to slide, she said. “By saying it’s differentiated, we’re basically saying Vesta was a little planet trying to happen.”

Most asteroids are pretty simple. “They’re just like giant rocks in space,” said Buczkowski. But previous research has found signs of igneous rock on Vesta, indicating that rock on Vesta’s surface was once molten, a sign of differentiation. If the troughs are made possible by differentiation, then the cracks aren’t just troughs, they’re graben. A graben is a dip in the surface that forms when two faults move apart from each other and the ground sinks into the widening gap, such as in Death Valley in California. Scientists have also observed graben on the Moon and planets such as Mars.

The images from the Dawn mission show that Vesta’s troughs have many of the qualities of graben, said Buczkowski. For example, the walls of troughs on simpler asteroids such as Eros and Lutetia are shaped like the letter V. But Vesta’s troughs have floors that are flat or curved and have distinct walls on either side, like the letter U — a signature of a fault moving apart, instead of simple cracking on the surface.

The scientists’ measurements also showed that the bottoms of the troughs on Vesta are relatively flat and slanted toward what’s probably a dominant fault, much as they are in earthly graben.

These observations indicate that Vesta is also unusually planet-like for an asteroid in that its mantle is ductile and can stretch under a lot of pressure. “It can become almost silly putty-ish,” said Buczkowski. “You pull it and it deforms.”

Buczkowski and her colleagues’ arguments for differentiation of Vesta are interesting, said Geoff Collins of Wheaton College in Norton, Massachusetts, who specializes in tectonics, the structure and motion of planetary crusts. “On many much smaller asteroid bodies, we’ve seen very narrow troughs that look just like cracks on the surface,” said Collins, who was not involved in the new study, “but nothing that looks like a sort of traditional terrestrial graben that you’d find on Mars or the Moon where things have really been pulled apart.”

But Collins is not yet fully convinced that Vesta’s troughs are graben. An example of rock-solid evidence of graben on Vesta that has yet to be discovered, he said, would be an obvious crater that had been torn in two by a trough.

There are other qualities of Vesta that could be clues to how the troughs formed. For example, unlike the larger asteroid Ceres, Vesta is not classified as a dwarf planet because the large collision at its south pole knocked it out of its spherical shape, said Buczkowski. It’s now more squat, like a walnut. But if Vesta has a mantle and core, that would mean it has qualities often reserved for planets, dwarf planets, and moons — regardless of its shape.

The origin of that funny shape is the centerpiece of a different hypothesis about how the troughs formed. Britney Schmidt of the Institute for Geophysics in Austin, Texas, believes the south pole collision knocked Vesta into its current speedy rate of rotation about its axis of about once per 5.35 hours, which may have caused the equator to bulge outward so far and so fast that the rotation caused the troughs, rather than the direct power of the impact. “It’s an enigma why Vesta rotates so quickly,” said Schmidt, who was not a part of the current study.

Dawn has already left to explore Ceres, so all the data it will retrieve on Vesta is in hand. Buczkowski said scientists will continue to sort that data out and improve on computer simulations of Vesta’s interior. As those analyzes come along, she said she will keep an open mind toward any revelations that come to light, but she doesn’t expect her conclusion will change. “I really think that these are graben,” she said.