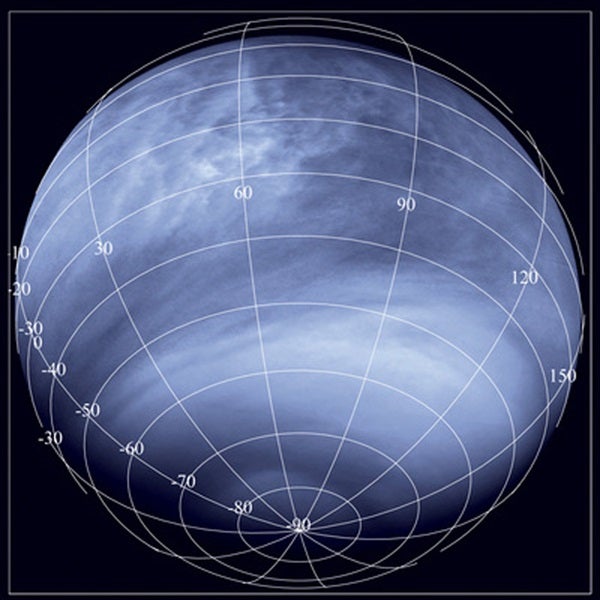

It shows numerous high-contrast features caused by an unknown chemical in the clouds that absorbs ultraviolet light, creating the bright and dark zones.

With data from Venus Express, scientists have learned that the equatorial areas on Venus that appear dark in ultraviolet light are regions of relatively high temperature where intense convection brings up dark material from below. In contrast, the bright regions at mid-latitudes are areas where the temperature in the atmosphere decreases with depth. The temperature reaches a minimum at the cloud tops, suppressing vertical mixing. This annulus of cold air, nicknamed the “cold collar,” appears as a bright band in the ultraviolet images.

The European Space Agency’s (ESA) Venus Express is helping planetary scientists investigate whether Venus once had oceans. If it did, it may have begun its existence as a habitable planet similar to Earth.

Earth and Venus seem completely different today. Earth is a lush, clement world teeming with life while Venus is hellish, its surface roasting at high temperatures.

But underneath it all, the two planets share a number of striking similarities. They are nearly identical in size, and now thanks to ESA’s Venus Express orbiter, planetary scientists are seeing other similarities, too.

“The basic composition of Venus and Earth is very similar,” said Hakan Svedhem, ESA Venus Express project scientist. Planetary scientists from around the world will be discussing just how similar Venus and Earth are in Aussois, France, where they are gathering this week for a conference.

One difference stands out: Venus has very little water. Were the contents of Earth’s oceans to be spread evenly across the world, they would create a layer 1.9 miles (3 kilometers) deep. If you were to condense the amount of water vapor in Venus’ atmosphere onto its surface, it would create a global puddle just 1.2 inches (3 centimeters) deep.

Yet, there is another similarity here. Billions of years ago, Venus probably had more water. Venus Express has certainly confirmed that the planet has lost a large quantity of water into space. The loss of water happens because ultraviolet radiation from the Sun streams into Venus’ atmosphere and breaks up the water molecules into atoms. These then escape into space.

Venus Express has measured the rate of this escape and confirmed that roughly twice as much hydrogen is escaping than oxygen. It is believed that water is the source of these escaping ions. It has also shown that a heavy form of hydrogen, called deuterium, is progressively enriched in the upper echelons of Venus’ atmosphere because the heavier hydrogen will find it less easy to escape the planet’s grip.

“Everything points to there being large amounts of water on Venus in the past,” said Colin Wilson at Oxford University in the United Kingdom. But that does not necessarily mean there were oceans on the planet’s surface.

Eric Chassefiere from the Universite Paris-Sud in France has developed a computer model that suggests the water was largely atmospheric and existed only during the earliest times when the surface of the planet was completely molten. As the water molecules were broken into atoms by sunlight and escaped into space, the subsequent drop in temperature probably triggered the solidification of the surface. In other words: No oceans.

Although it is difficult to test this hypothesis, it is a key question. If Venus ever did possess surface water, the planet may possibly have had an early habitable phase.

Even if true, Chassefiere’s model does not preclude the chance that colliding comets brought additional water to Venus after the surface crystallized, and these created bodies of standing water in which life may have been able to form.

There are many open questions. “Much more extensive modeling of the magma ocean-atmosphere system and of its evolution is required to better understand the evolution of the young Venus,” said Chassefiere.

When creating those computer models, the data provided by Venus Express will prove crucial.