A new finding casts doubt on the 2006 report that the bright spots in some Martian gullies indicate that liquid water flowed down those gullies sometime since 1999.

“It rules out pure liquid water,” says lead author Jon D. Pelletier of the University of Arizona in Tucson.

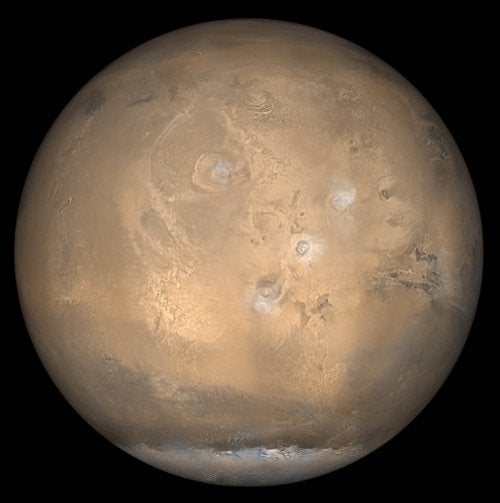

Pelletier and his colleagues used topographic data derived from images of Mars from the High Resolution Imaging Science Experiment (HiRISE) camera on NASA’s Mars Reconnaissance Orbiter. Since 2006, HiRISE has been providing the most detailed images of Mars ever taken from orbit.

The researchers applied the basic physics of how fluid flows under Martian conditions to determine how a flow of pure liquid water would look on the HiRISE images versus how an avalanche of dry granular debris such as sand and gravel would look.

“The dry granular case was the winner,” says Pelletier, a UA associate professor of geosciences. “I was surprised. I started off thinking we were going to prove it’s liquid water.”

Finding liquid water on the surface of Mars would indicate the best places to look for current life on Mars, says co-author Alfred S. McEwen, a UA professor of planetary sciences.

“What we’d hoped to do was rule out the dry flow model, but that didn’t happen,” says McEwen, the HiRISE principal investigator and director of UA’s Planetary Image Research Laboratory.

An avalanche of dry debris is a much better match for their calculations and also what their computer model predicts, says Pelletier and McEwen.

Pelletier says, “Right now the balance of evidence suggests that the dry granular case is the most probable.”

They add that their research does not rule out the possibility that the images show flows of very thick mud containing about 50 percent to 60 percent sediment. Such mud would have a consistency similar to molasses or hot lava. From orbit, the resulting deposit would look similar to that from a dry avalanche.

In December 2006, Michael Malin and his colleagues published an article in the journal Science suggesting the bright streaks that formed in two Martian gullies since 1999 “suggest that liquid water flowed on the surface of Mars during the past decade.”

Malin’s team used images taken by the Mars Global Surveyor Mars Orbital Camera (MOC) of gullies that had formed before 1999. Repeat images taken of the gullies in 2006 showed bright streaks that had not been there in the earlier images.

Subsequently, Pelletier and McEwen were at a scientific meeting and began chatting about the astonishing new finding. They discussed how the much more detailed images from HiRISE might be used to flesh out the Malin team’s findings.

Pelletier had experience in using the stereoscopic computer-generated topographic maps known as digital elevation models (DEMs) to figure out how particular landscape features form.

DEMs are made using images of the landscape taken from two different angles.

The Mars Reconnaissance Orbiter spacecraft is designed to regularly point at targets, enabling high-resolution stereo images, McEwen says.

Kirk made a DEM of the crater in the Centauri Montes region where the Malin team found a new bright streak in a gully.

Once the DEM was constructed, Pelletier used the topographic information along with a commercially available numerical computer model to predict how deposits in that particular gully would appear if left by a pure water flood versus how the deposits would appear if left by a dry avalanche.

The model also predicted specific conditions needed to create each type of debris flow.

“This is the first time that anyone has applied numerical computer models to the bright deposits in gullies on Mars or to DEMs produced from HiRISE images,” Pelletier says.

When he compared the actual conditions of the bright deposit and its HiRISE image to the predictions made by the model, the dry avalanche model was a better fit.

“The dry granular case is both simpler and more closely matches the observations,” Pelletier says. “It’s just a test. It’s either more like A or more like B. We were surprised that it was more like B.”

Pelletier says these new findings indicate, “There are other ways of getting deposits that look just like this one that do not require water.”

One of the team’s next steps is using HiRISE images to examine similar bright deposits on less-steep slopes to sort out what processes might have formed those deposits.