Just a year ago, the headline “NASA Confirms Evidence That Liquid Water Flows on Today’s Mars” buoyed excitement for the possibility of life on the red planet.

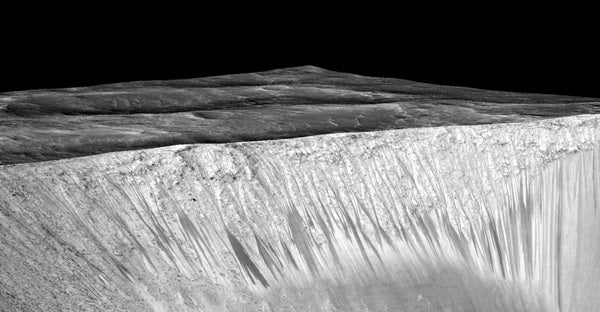

The claim, based on a paper published in Nature Geoscience, relied on the presence of mysterious dark streaks on Mars called recurring slope lineae (RSL). After detecting the presence of hydrated salts at four different locations on the RSL, researchers concluded that water likely played a role in their formation. That’s because hydrated salts precipitate from liquid water, and so their discovery on the seasonally recurring RSL suggests that water—albeit briny water—may flow on Mars.

Or does it? A study published in Nature Communications on November 11th offers new evidence that our red planet neighbor is extremely dry, and has been that way for millions of years.

The study, led by Christian Schröder, a Lecturer in the Biological and Environmental Sciences at the University of Sterling in the United Kingdom, used a new strategy to analyzing the moisture on Mars. By looking at the oxidation of iron in stony meteorites—in other words, how fast they were rusting—the researchers were able to determine that the chemical weathering rate on Mars was about 1-4 orders of magnitude slower than the slowest rates on Earth. Since weathering rates are affected by water moisture, this means that Mars likely has a “dry and desiccating environment,” according to the study.

The extremely slow chemical weathering of iron suggests no evidence for liquid water, the researchers continued in their study.

Of course, given that the meteorites show some oxidation of iron, albeit at extremely slow rates, water plays some contributing role. However, it’s “very unlikely that it’s flowing water,” Schröder says. Instead, he hypothesized that it is vapor that occasionally condenses onto the meteorites.

And what about the 2015 study that led to the eye-catching headline about liquid water on Mars? Schröder emphasized that their latest study does not contradict that data, noting that the limited alteration seen on meteorites is due to water. However, “it kind of puts an upper limit onto that water, and says that even though there might be some moisture, it’s all relative and it’s very little.”

Matthew Chojnacki, an Associate Staff Scientist at the Lunar Planetary Laboratory at the University of Arizona, and one of the authors of the 2015 paper, spoke to Astronomy about Schröder’s new study. “I thought it was a very novel approach,” he said, of the team’s use of chemical weathering rates to analyze water moisture.

“The paper comes back to this tale of two worlds, and pieces of evidence that point us in two different directions,” Chojnacki says. While geochemical evidence seems to suggest that Mars has been dry for a long time, geomorphological evidence (including delta-like features and streamlined islands seen on Mars) seem to point to the presence of contemporary water.

“A lot of Mars studies tend to contradict each other,” Chojnacki said. “And that’s not the scientists—it’s the data. It depends on the data approach you take.”

Chojnacki did accede that if RSL are caused by contemporary water—even briny, salty water—we would likely see faster chemical weathering rates than what Schröder’s team found. However, it’s possible that the places where Schröder and his colleagues analyzed the meteorites are dryer than spots where RSL are found. “The findings don’t necessarily change my view much,” he added.

Schröder disagrees. “I would not say that the atmosphere contains more moisture in other regions,” he told Astronomy. But more data, both geochemical and geomorphological, will continue to shed light on one of the most fascinating controversies about the planet that—in the not-so-distant future—some hope to call home.