Some things look weird. Others have peculiar characteristics that are not at all visually obvious, like extreme density. Still others earn their strangeness points solely because of bad behavior. It is extremely rare for anything to win in all these categories at once, but that is the case with the astonishing star Eta Carinae and the bizarre nebula surrounding it.

Bringing the universe to your door. We’re excited to announce Astronomy magazine’s new Space and Beyond subscription box – a quarterly adventure, curated with an astronomy-themed collection in every box. Learn More >>.

Britain’s Royal Astronomer Edmond Halley was the first to catalog this 4th-magnitude star in the southern constellation Carina the Keel in 1677. When it received its (Johann) Bayer designation, always a lowercase Greek letter, its modest brightness earned it only that alphabet’s seventh letter, Eta (η). But by the early 1700s, observers sailing far south of Europe, where it is never seen, noted that Eta Carinae had brightened so much that it was now one of the constellation’s most prominent stars.

It then dimmed for decades but in 1820 started brightening again until, in 1841, the star surpassed magnitude 0. It peaked in April 1843 as the second-brightest star in all the heavens at a dazzling magnitude –0.8, not much inferior to the Dog Star Sirius. Considering that the latter is only 8.6 light-years away while Eta is some 8,000, this accomplishment was, to say the least, impressive.

At that great distance — far beyond all the night sky’s notable stars — Eta Carinae must have been emitting almost as much light as a supernova explosion. And yet the outburst failed to destroy the star. Later, astronomers found a half dozen other “supernova impostors” or “false supernovae” in distant galaxies, but none other than Eta was ever again seen in our Milky Way. One of those false supernovae popped off into a real one just a few years later, and no one doubts that Eta is ready to blow at any moment, too. Of course, in astro-speak, momentarily could mean a million years from now. But it could also mean tomorrow.

While the two main varieties of genuine supernovae contain some mysteries, these false supernovae are far more baffling. The event exhibited by Eta a century and a half ago may be due to a kind of surface instability that never progressed further, with the star more or less recovering its previous composure. Or perhaps the star’s astounding luminosity creates a buildup of radiation pressure that then undergoes a sudden release.

That the star is extreme is beyond doubt. Eta is some 4 million times brighter than the Sun. It was long regarded as possibly the most massive star in the known universe. However, astronomers recently learned that its light comes from a pair of orbiting suns, with the main Eta star boasting nearly 100 solar masses all by itself. This dual nature is probably somehow involved in its brightness fluctuations.

Eta Carinae’s dazzling brilliance faded after 1843, and for the first half of the 20th century, it went in the opposite direction, like Alice, becoming utterly invisible to the naked eye. It remained a dim 8th-magnitude binocular target until World War II. Then, it re-brightened and has recently been dimly visible without any optical aid, occasionally reaching almost 4th magnitude.

Why does it vary? Astronomers assumed simple eclipses were the culprit, but those exhibit perfect regularity. In 2008, the expected dimming happened much too early, sending astronomers back to the drawing board. Perhaps the interaction between the two superluminous components sucks material from one or both, and this blocks some of the outgoing light. No one really knows.

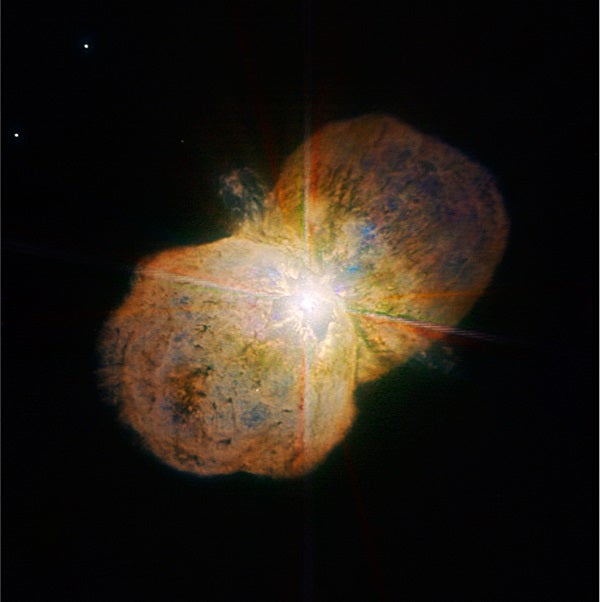

Since stars are mere pinpoints of light through even the largest telescopes, Eta’s strange behavior would normally be unaccompanied by any suitably peculiar photograph. But something happened during Eta’s outburst in 1841 that made it mutate from a dot to an eerie monstrosity. The sun’s explosion created a bizarre pair of lobes, looking like tangential bubbles. This astounding gaseous configuration is called the Homunculus Nebula.

Apparently, the near-supernova violence didn’t race outward from Eta evenly in all directions. Rather, perhaps because of the combined distorted peanut shape of the central stars, or else an interaction from the blast at the time of explosion, shock waves produced a kind of boundary that meteorologists call a standing wave. This divided the outrushing material into dual spheres, each expanding at 415 miles (668 kilometers) per second. At this velocity, the Homunculus has grown so large, so quickly that even at its distance of nearly 8,000 light-years, we can observe odd radial streaks and dust lanes in the ever-growing bubbles.

The nebula’s narrow middle section glows violet, marking the position of Eta itself. In all likelihood, this central region was blown clear of obscuring dust, which lets shorter blue wavelengths escape, while the bipolar lobes are dustier so that only red light leaks out.

Altogether, we witness a tomb of mystery, a bizarre sanctum that generates more guesses than answers — in a very perilous neighborhood.