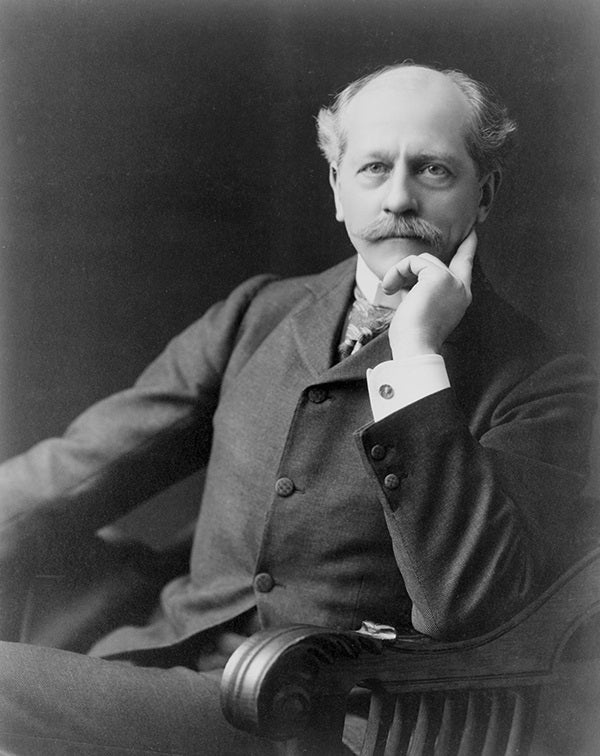

A century ago, the whole world — and especially famed astronomer Percival Lowell (1855–1916) — believed an unseen “Planet X” gravitationally tugged on Uranus and Neptune. Among the reasons the wealthy Lowell founded his Flagstaff, Arizona, observatory was his hope of detecting this hypothesized ninth planet.

In February 1930, 23-year-old Lowell Observatory employee Clyde Tombaugh inspected two images of Gemini, taken a month earlier on January 23 and 29, and found that a faint star had changed position. The observatory waited until March 13, the anniversary of Uranus’ discovery 149 years earlier (and Lowell’s birthday), to announce the new planet to the world.

Bringing the universe to your door. We’re excited to announce Astronomy magazine’s new Space and Beyond subscription box – a quarterly adventure, curated with an astronomy-themed collection in every box. Learn More >>.

Lowell Observatory had first dibs at naming the object and received more than a thousand ideas. An 11-year-old British girl, Venetia Burney, suggested Pluto because she thought the Roman god of the underworld would be a perfect namesake for a planet condemned to orbit so far from the Sun. The Lowell staff, after narrowing the long list of potentials to Cronus, Minerva, and Pluto, ultimately chose the last because its first two letters also happened to be the initials of the observatory’s namesake.

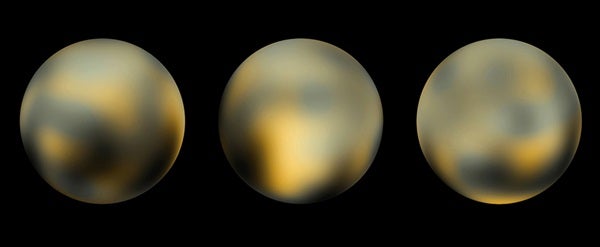

But Pluto was odd from the get-go. Its orbit was not roughly circular like other planets. Instead, its lengthy 248-year orbital track carried it from 30 times the Sun-Earth distance to nearly 50. Moreover, its path wasn’t just oval like a race track, but it also inclined 17° to the plane of the solar system.

As if this wasn’t weird enough, when looking down from above, Pluto’s lopsided orbit appears to cross Neptune’s. Seen in 3-D, however, Pluto is then actually highest above the plane of the solar system. It turns out that Pluto has an odd stable resonance with Neptune, in which Pluto performs two orbits of the Sun in the same time that Neptune makes three. The two are connected in a strange way where their mutual gravities paradoxically keep them permanently far apart. Indeed, Pluto ventures closer to Uranus than it ever gets to Neptune!

Pluto’s extreme faintness suggested it was a small body, and some originally thought it Earth-sized. But as the years passed, various observations first indicated it was only 1/10 Earth’s mass, then 1/100, and finally just 1/500 our planet’s mass. This made it only 69 percent the Moon’s width, so that it couldn’t have been the object tugging at Neptune and Uranus after all. Its discovery was just a freakish accident.

The next plutonian oddity arose in 1978 when James Christy discovered it has a moon, soon named Charon. Charon and Pluto are so similar in size — the moon is half as wide as the planet — that they’re more like a double planet. Charon does not orbit Pluto but instead circles an empty spot in space around which they both revolve every 6.4 days. Meanwhile, each body spins in that same period, too, so that both keep one hemisphere forever staring at the other.

Many astronomers quickly regarded Charon not as a moon but as one-half of a peculiar double-planet system, even after the Hubble Space Telescope found two more tiny moons, named Nix and Hydra, in May 2005. (Astronomers have since discovered two more.)

But another 2005 discovery changed everything. In July, astronomers found a celestial body that was soon named Eris. It was more distant than Pluto, but, more importantly, it had a greater mass. Astronomers had already discovered that the Kuiper Belt — a crowded band of icy bodies just beyond Neptune — contained many orbiting objects, even spherical ones. Clearly, lots of “Plutos” lurked out there. Eris was just the last straw.

Pluto, tiny and weirdly orbiting, could remain a bonafide-if-odd double planet only if these other objects were now also inducted into the Hall of Planets. The member list seemed poised to expand, first to about a dozen new tiny planets with bizarre cockeyed orbits, and, it was expected, eventually to hundreds more.

The other alternative was to acknowledge that these distant, icy, minuscule bodies with wildly eccentric orbits and large inclinations to the plane of the solar system differed too much from the first eight planets. In 2006, the International Astronomical Union decreed that this latter group would henceforth be known as “dwarf planets.” Thus, Pluto got demoted.

Meanwhile, a spacecraft dedicated to explore it — New Horizons — and containing some of the ashes of discoverer Clyde Tombaugh, blasted off January 19, 2006, a mere nine months before distant Pluto was reclassified.

Later this year, on July 14, New Horizons will arrive at a different type of object than the one to which it was launched, and astronomers will finally get to see Pluto’s oddities up close.