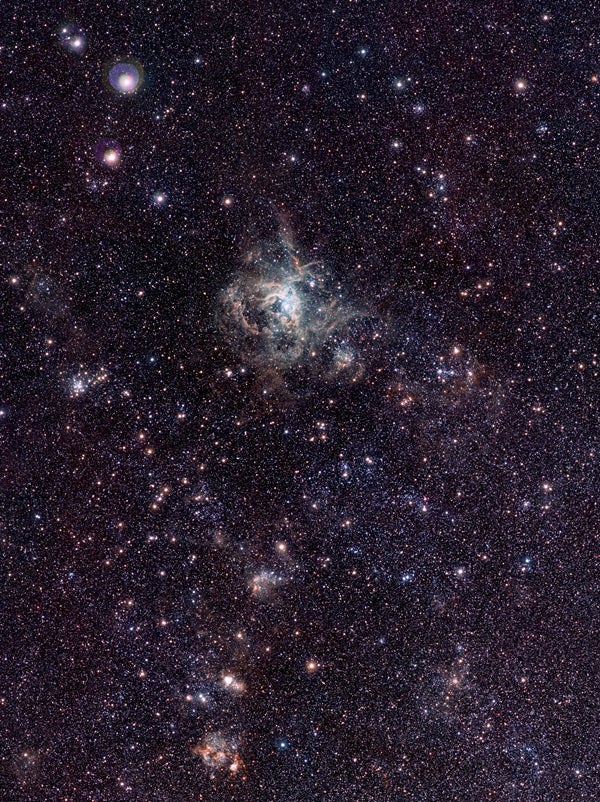

Like residents of New York City or Paris who, with some justification, regard themselves as living in the cultural centers of the world, we Milky Way inhabitants may thumb our noses at our little smudgy companion galaxy, the Large Magellanic Cloud (LMC). Looking like a detached piece of Milky Way in our far southern sky, the LMC’s nature as an independent dwarf galaxy long went unsuspected. Even now, knowing it lies far beyond all the night’s naked-eye stars at a distance of 160,000 light-years, its gray monochrome glow gives no hint of anything remarkable.

But even binoculars pointed its way will reveal a smudgy spot that grows more astonishing and beautiful with each optical power step-up. It took more than 140 years after the creation of the first telescope — until the observations of Nicolas Louis de Lacaille in 1751 — for astronomers to apprehend this blotch’s nebular nature. Soon called the Tarantula Nebula (NGC 2070) because of its spidery, multicolored tentacles, it is possibly the most beautiful entity in the known universe.

Bringing the universe to your door. We’re excited to announce Astronomy magazine’s new Space and Beyond subscription box – a quarterly adventure, curated with an astronomy-themed collection in every box. Learn More >>.

More important for our agenda of spotlighting the weirdest, the Tarantula is strangely enormous. It dwarfs all other star-forming regions and glowing nebulae — in both our galaxy and even the larger Andromeda Galaxy. We cannot glimpse anything like it anywhere among the four dozen members of our Local Group of galaxies. Its size is obvious using a simple apples-to-apples comparison. The most famous gas cloud in our neck of the celestial forest is the Orion Nebula (M42), some 30 light-years across. The Tarantula’s 700-light-year extent means that if it sat at M42’s 1,500-light-year distance from Earth, it would occupy one-third of our sky from the horizon to the zenith — fully 60 Full Moons in a row! Its light would be intense enough to cast shadows.

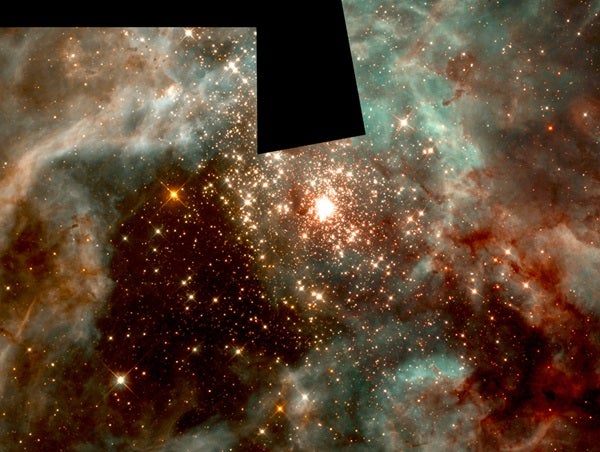

The Tarantula’s immense expanse of gaseous hydrogen glows vividly, excited by the fierce ultraviolet light of … something. What can possibly cause this much substance to light up like Times Square? The answer is as amazing as the Tarantula Nebula itself. At the heart of this vast labyrinthine nebula is what many once assumed was the most massive star in the universe, named 30 Doradus. In recent years, ultra-sharp Hubble Space Telescope images showed that this is not a single sun at all, but rather an extraordinary group of unique stars occupying the center of a so-called “super star cluster” unlike anything in our Milky Way Galaxy.

Called R136, it has the same mass as 450,000 Suns. In sheer bulk, it resembles our galaxy’s globular clusters — except ours are all fashioned from ancient stars while these are anything but. The compact star cluster R136 occupies only 35 light-years of celestial real estate, yet it produces enough energy to light up the vast Tarantula Nebula and make it visible across the ocean of intergalactic space. All of its stars are so young — just 1 to 2 million years have elapsed since their fusion cores ignited — that the first humans already occupied caves and prepared their undercooked haute cuisine before these suns existed. Nonormal-mass stars can be found here; all are luminous blue giants and supergiants boasting the rarest spectral type, O. And “early O” at that, with 39 confirmed stars with the ultra-hot, ultra-massive designation of O3.

Hubble and other major telescopes have found that R136 has a central component sun named R136a that was long believed to be a “hypergiant” of 1,500 solar masses. It was once listed as the most massive star in the universe, its radius 60 times greater than our star’s. Recently, by employing a new cool-sounding procedure called “holographic speckle interferometry,” we now recognize R136a as a dozen massive, luminous suns forming a newborn star cluster of record-breaking density.

Although freshly demoted from its former 1,500-Sun-mass status, these individual stars nevertheless remain amazing. Each holds between 37 and 76 solar masses, and they hover so close to each other that their mutual motion is a complex interwoven minuet. One of these freshly baked, newfound stars, with the logical but hardly frat-house nickname of R136a1, wins our superlative trophy as the new most massive star in the known universe. Its weight is 265 solar masses. This bestows it with such intense core pressure that its nuclear fusion generator feverishly cranks out more light than any other star in the cosmos. It shines with the light of 10 million Suns, all by itself.

So here is the largest, brightest nebula with the heaviest, most luminous star inside the most massive newborn cluster. By defining the edge of the envelope in these categories, the Tarantula Nebula and R136 easily earn their 15 light-years of fame.

As if to add an unnecessary exclamation point, the first naked-eye supernova since 1604 went kaboom in the outskirts of the Tarantula Nebula in 1987. Suddenly, eyes everywhere turned anew to this most remarkable and stunning nebula in all the heavens.