Picture a gentle landscape of hilly sand dunes leading down to a tranquil lake, whose surface starts rippling in the afternoon wind, disturbing the reflection of the few white clouds drifting above. On the opposite shore, a sudden rainstorm wets the stones and pebbles. It feels as if a sunset is unfolding because the entire sky is pumpkin colored.

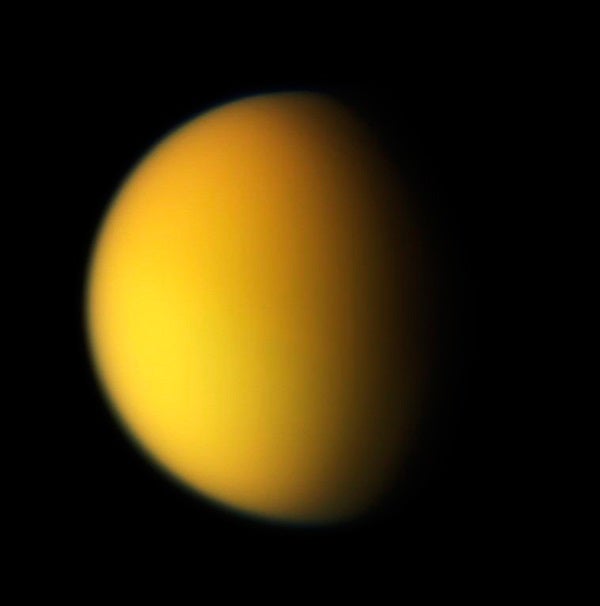

Welcome to the surface of Saturn’s giant moon Titan, the only known satellite with an appreciable atmosphere and all the changing weather that goes with it. The air here is about 11/2 times thicker than ours, and, like ours, mostly nitrogen. Combined with its low gravity — comparable to what the Apollo astronauts experienced while hopping around on the Moon — such soupy air would let people easily fly around by flapping their arms courtesy of cardboard wings.

Bringing the universe to your door. We’re excited to announce Astronomy magazine’s new Space and Beyond subscription box – a quarterly adventure, curated with an astronomy-themed collection in every box. Learn More >>.

Saturn’s satellite sounds like a fun place — a sort of bizarre, amusement-park variation of our world. It even might harbor unique forms of life, perhaps on its surface, or maybe underground. But Titan is not so jolly-weird — it’s scary-perilous.

This titanic story began in 1655 when Dutch astronomer Christiaan Huygens (HOY-ghens) first realized that the odd “teacup handles” Galileo Galilei thought were affixed to Saturn a few decades earlier were really unattached rings encircling the planet. Huygens then went on to discover a moon orbiting the ringed world. In one of the greatest recorded moments of unimaginativeness, he named it Saturni Luna — Latin for Saturn’s moon. It took almost two centuries before John Herschel suggested something better: Titan. The world quickly agreed.

For 300 years, astronomers regarded Titan as the solar system’s largest satellite, and for an interesting reason. Its thick opaque atmosphere, unsuspected until the 20th century, exaggerated its dimensions like a bird puffing out its feathers. Nowadays, Saturn’s largest moon is number two overall, bested only by Jupiter’s Ganymede. But at more than 3,000 miles (4,800 kilometers) across, Titan is still larger than Mercury, dwarfs our Moon by 50 percent, and is twice the size of the demoted ex-planet Pluto.

That said, Titan’s thick, opaque air blocks its surface from view, creating a tantalizing mystery. What might lurk below? In 1981, programmers decided to send the Voyager 1 spacecraft for a close-up look, even though such a trajectory meant flinging the probe sideways so that it couldn’t later explore Uranus and Neptune. The sacrifice didn’t pan out: Voyager’s cameras could not penetrate the clouds.

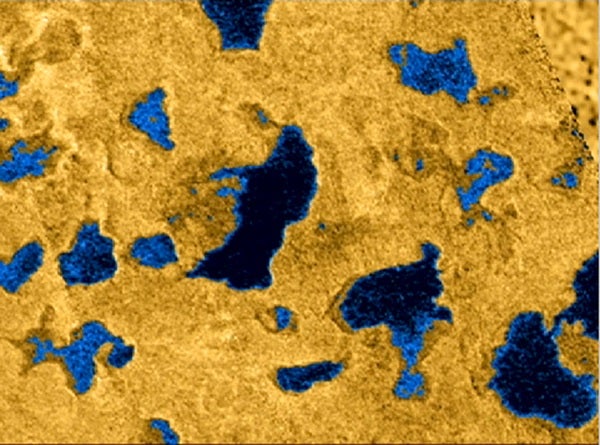

Two decades later, the Cassini spacecraft set off much better prepared. It arrived equipped with an attached flying-saucer-shaped lander — the Huygens probe — that descended through the smog with its camera clicking. The results astonished everyone. Here was the only celestial body besides Earth with lakes of liquid and rain falling from clouds. The super-cold temperature of –270° Fahrenheit (–168° Celsius), however, meant that liquid water was out of the question. Instead, the terrestrial-seeming landscape of boulders and countless lakes offered a twist. The stones were solid water ice, which at such temperatures is hard as rock. And the liquid was actually methane, which on Earth is a flammable gas — the vapors emitted by the part of cows that don’t say “moo.”

Scientists still debate whether the interior of Titan is hot and, if so, whether water mixed with ammonia (which would preserve liquid at much lower temperatures) lurks there, with all the juicy implications for subsurface life. The more obvious possible-life discussion is in plain sight, in Titan’s methane lakes.

Naturally, we assume life requires water. Nonetheless, astrobiologists can picture extraterrestrials taking in hydrogen instead of oxygen, where it would react internally with acetylene instead of glucose. The byproduct — what these creatures would breath out — would be methane instead of the carbon dioxide we exhale. In 2005, NASA planetary scientist Chris McKay suggested life that consumed methane would measurably alter the atmosphere in ways we could detect on Earth. In 2010, a Johns Hopkins University scientist claimed there was indeed such evidence in an odd excess of hydrogen in Titan’s upper atmosphere, while it’s nearly totally absent at its surface despite strong downdrafts. One implication is that methane-addicted organisms eat the hydrogen.

That same year, others found an odd surface paucity of acetylene, which could also imaginatively mean that its scarcity results from methanogenic E.T.s munching on it.

So, could methane provide a medium for life instead of water? It’s far too early to say because some sort of non-life chemistry could also account for these observed oddities. For the moment, we’re left with a cold, thick nitrogen atmosphere containing intriguingly abundant organic substances, a dynamic weather system that transports gases and liquids in strong dune-creating winds, and a landscape that is forever resculpted.