What was the most astonishing scientific announcement of all time? In terms of sheer visceral impact, it was probably the discovery of Uranus in 1781.

Hold on. Uranus? Astounding?

Today, the giant aquamarine gas ball that constitutes the seventh planet in our solar system inspires as much awe as a bologna sandwich. But things were different in the late 18th century. The age of science and reason was well advanced. In that era, when new discoveries were commonplace, what could possibly prove astonishing enough to cause global distress and bewilderment? Answer: Finding that some basic aspect of nature was different from the deepest, most long-held truisms.

Bringing the universe to your door. We’re excited to announce Astronomy magazine’s new Space and Beyond subscription box – a quarterly adventure, curated with an astronomy-themed collection in every box. Learn More >>.

Everyone took the existence of five (and only five) planets beyond Earth for granted since the dawn of sky watching. Nobody even bothered looking for any others. Therefore, when German-born British astronomer William Herschel spotted Uranus on March 13, 1781, and announced it as a new comet on April 26, he was far from the first to have laid eyes on that 6th-magnitude “star.” Nearly a century earlier, English astronomer John Flamsteed listed it in his catalog as 34 Tauri. The real oddity: Why hadn’t anyone noticed its motion? Uranus is dimly but clearly visible to the naked eye. It changes position. How had it escaped all the keen-eyed Arab desert dwellers who named the stars in the first place? And what about the first 171 years of telescopic observation? Uranus is brilliant through a scope.

Herschel named the planet Georgium Sidus (George’s Star) to butter up his newfound patron King George III. Others wanted to name it Herschel. Eventually, it was decided that since Saturn was the father of Jupiter, well, the next planet outward, Uranus — who in Greek mythology is the father of Saturn — would provide a perfect classical continuation. Unfortunately, Uranus is the most mispronounced celestial object, and few non-astronomers correctly say YUR-uh-nus.

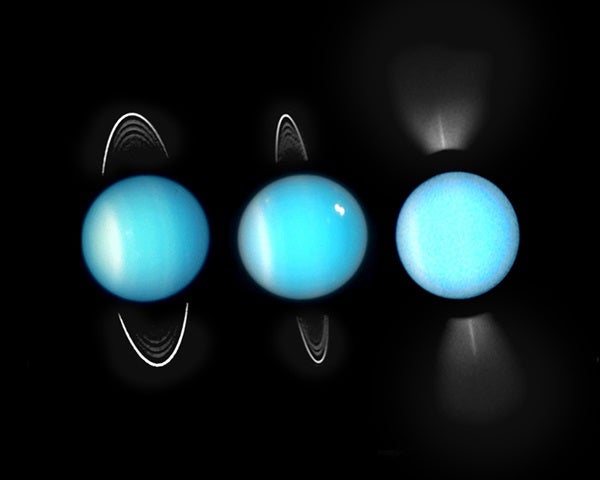

Its odd discovery story is not what earns it a place in 50 Weirdest, however. Nor even the fact that it owns several superlatives as the coldest planet, the only truly green celestial body, and also the place with the strongest winds, which routinely blow more than 500 mph (800 km/h). All of these things help make Uranus deliciously peculiar. But its greatest craziness lies in how it spins.

All other planets in the solar system twirl with their poles at the top and bottom as they fly through space, and with their equators in the same plane, pretty much facing the Sun. But Uranus’ poles are tipped 98°, almost sideways.

Because Uranus’ spin axis roughly aligns with the solar system’s plane, it’s like a rolling ball, with rotation axes on the sides instead of at the top. When the only spacecraft that ever came near it, Voyager 2, zoomed 50,640 miles (81,500 km) over its cloud tops January 24, 1986, it happened very nearly at the time of a rare uranian solstice. The planet was essentially oriented like an archery target, with its south pole in the middle, pointed toward the Sun and Earth. Our telescopes then showed its moons going around it like the hands of a clock. With one pole continuously facing the Sun, Uranus’ southern hemisphere experienced a nonstop 42-Earth-year summer, while its northern hemisphere suffered an equal period of depressing blackness.

As Uranus slowly chugged along in its 84-year orbit, spending seven years in each zodiacal constellation, its orientation gradually changed until its equinox arrived December 7, 2007. Then the story was utterly different. Its poles were now on the right and left sides of Uranus, essentially marking the leading and trailing spots on the planet as it flew through space. At that time, its equator finally faced the Sun, but aligned vertically instead of horizontally like the other planets. Its moons, which orbit the equator, no longer traced out circles around the Uranus’ limb. Now they went straight up and down like an elevator as they orbited that vertical equator.

Why is Uranus on its side? Another planet probably hit it in its youth. When you factor in this with its intense green color caused by its mysteriously abundant methane, its howling winds, and its icy temperatures, among other things, then you have what is arguably the strangest gas giant of all — no matter how you pronounce it.