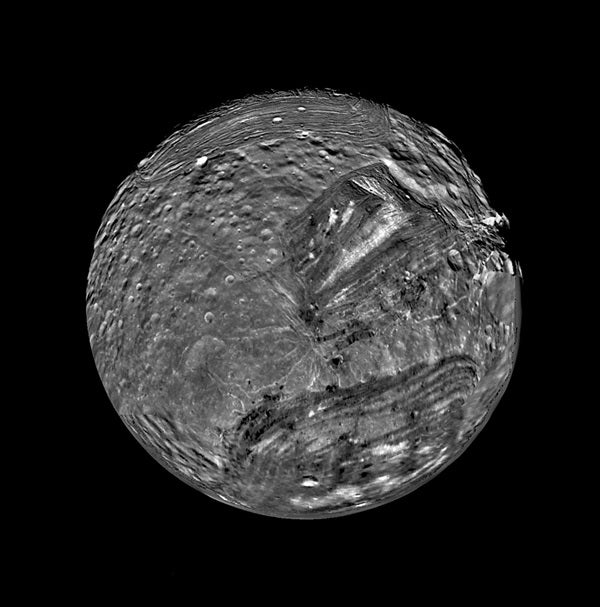

Beyond our solar system, symmetry rules. Except for the modern-art tapestries of diffuse nebulae, most objects — star clusters, elliptical galaxies, and stars — look more or less the same from every angle. That’s also true for most nearby objects like the Sun or Saturn. When a celestial body has wildly different hemispheres, like our Moon, it turns heads. But with Uranus’ nearest major satellite, Miranda, the odd appearance goes off the charts into the Pablo Picasso bizarre.

We might not have ever really known about this except for a major piece of good luck. Ever since its discovery in 1948, this super-dim 16th-magnitude satellite has appeared as no more than a tiny dot in even the largest telescopes. Fortunately, we had one chance for a close-up visit to all of Uranus’ five

then-known satellites when the plucky Voyager 2 spacecraft, limping along with a backup radio, was scheduled to whiz past in 1986.

Miranda wasn’t a priority, however. Nothing known about this moon had piqued anyone’s interest. The spacecraft trajectory was carefully chosen with only one objective in mind: It must precisely use the uranian system’s gravity as a slingshot to curve the probe’s path toward its next destination, the planet Neptune, 3 years later.

Bringing the universe to your door. We’re excited to announce Astronomy magazine’s new Space and Beyond subscription box – a quarterly adventure, curated with an astronomy-themed collection in every box. Learn More >>.

Turns out, that trajectory would carry Voyager 2 far closer to Miranda than any other of Uranus’ satellites. On January 24, 1986, it did just that, coming within 19,000 miles (30,000 kilometers). Despite traveling at the speed of light, the images it broadcast back to Earth required 2.5 hours to arrive, permitting no corrections or commands of any kind. The cameras had to automatically swivel precisely during each long and correct exposure in the dim sunlight to compensate for the spacecraft’s rapid speed, or else the pictures would be blurred.

Yet, when the photos were displayed back at NASA’s Jet Propulsion Laboratory, jaws dropped. The images were all perfect — but the scenes of Miranda’s surface were anything but. Here was a place like no other in the universe.

Previously, the surfaces of moons and planets mostly made sense. Our Moon’s craters and straight-line grooves were obviously caused by meteors striking at various angles. Its dark, smooth “seas” were clearly solidified lava. Few deep mysteries remained.

Not so on Miranda.

This world looks like a collage. It’s not difficult to believe some omnipotent used scissors and glue to combine features from several different places because the resulting panorama on this round, 290-mile-diameter (470km) moon just don’t belong together. Huge canyons cross its surface, apparently created by tectonic faulting. Some of these are 12 miles (19km) deep, dwarfing our planet’s Grand Canyon, which measures roughly 1 mile (1.6km) at its deepest point. In other places, terraced “steps” connect younger surfaces with seemingly older ones in a mix that makes no sense, appearing built from the inside out. Did lighter-density material once bubble up from below?

One popular alternative idea is that Miranda was shattered repeatedly by collisions during that Wild West-crowded period 4 billion years ago when solar system bombardments were de rigeur. Researchers think Miranda may have been completely shattered and then totally reformed, using various-sized blocks from its former incarnation, four or five times during its tumultuous history.

But what about that tectonic behavior? How does such a small body acquire that kind of inner heat? Experts say that nearby Uranus “must have” tidally heated the little moon, and that the plastic material “somehow” found a way to ooze up to fashion the carnival of disparate features.

This account would be OK except that some of Miranda’s facets defy any explanation. First and foremost is the huge “chevron,” which resembles the V-shaped stripes on a military uniform’s insignia. This strange grooved terrain with straight ridges and valleys seems to have replaced ancient cratered regions that once included gentle hills. Yet another different landscape appears along the top edge of Miranda’s disk, dominated by crisscrossing ridges and curvy troughs, cut short by grooved material. This area may have represented Miranda’s terrain at some intermediate point in its checkered history.

Miranda’s incoherent, thrown-together surface is unique on Earth or in the heavens. Theorists love tackling this kind of unprecedented newness, and each expert seems to have his or her own ideas. The real Miranda story, however, will likely remain unknown for two reasons. First, Voyager 2 couldn’t pause nor peer around to the far hemisphere. We thus have seen only this moon’s southern side and have no idea what lies over the horizon.

Secondly, no country currently has any plans to return; not one even has a “wish list” mission on the drawing board. If some financially flush science agency developed a sudden obsession today to visit the Uranian environment, the typical 6-year spacecraft development period, plus the long 9-year travel time, would still mean the soonest humanity might explore Miranda’s bizarre features would be 2026.

But don’t hold your breath. Miranda’s secrets are probably safe for the next decade and well beyond.