If a celestial object is the largest, smallest, brightest, or most distant, it defines one of the edges of the cosmic envelope. Only a single entity can be the “most this” or “greatest that.” They are automatically ultra-rare.

Venus owns at least seven such superlatives. It is the nearest planet to Earth. The brightest “star” in the sky. The body whose size best matches our planet’s. It has the most reflective clouds, making it the shiniest planet from our perspective, a property called “albedo.” It boasts the hottest surface and highest ground pressure in the solar system. And, not least, it’s the slowest-spinning object in the known universe.

Bringing the universe to your door. We’re excited to announce Astronomy magazine’s new Space and Beyond subscription box – a quarterly adventure, curated with an astronomy-themed collection in every box. Learn More >>.

Venus barely rotates at all. It needs 243 Earth days to make a complete turn, and just to be contrarian, it does this backward so that the Sun rises in the west and sets in the east. It all unfolds so lethargically that, even at the equator, a person could walk faster than the planet spins.

This makes Venus’ year shorter than its day. Or at least its day measured the usual way, against the stars. That backward spin, combined with its orbital motion, however, means that its solar day is a different story. The time from one sunrise to the next on Venus is 116.75 Earth days. This is interesting because five of these solar days exactly equals Venus’ 584-day synodic period, the time from when it’s first an evening star in our sky to its next evening star appearance. This cycle indicates that a peculiar gravitational lock-up exists between Venus and Earth.

Nightfall on Venus is nothing to celebrate. Its surface temperature of 860° F (460° C) doesn’t budge when the Sun sets. There’s no relief, although at least it’s a dry heat. The thick atmosphere creates a ground-level pressure 90 times greater than ours, or some 45 times higher than a pressure cooker. This Stygian combination of intense furnace heat, which manages to exceed even that of Mercury’s equator, plus Venus’ crushing pressure could cook a pot roast in a single second.

One benefit to life on Venus would be its easy weather forecasting. Every day, the conditions remain so constant that a venusian meteorologist could play the same recording: “Tomorrow, expect overcast and 860°, with a chance of lightning.” In 2010, researchers found that Venus’ lightning frequency matches ours, with 100 planet-wide flashes a second.

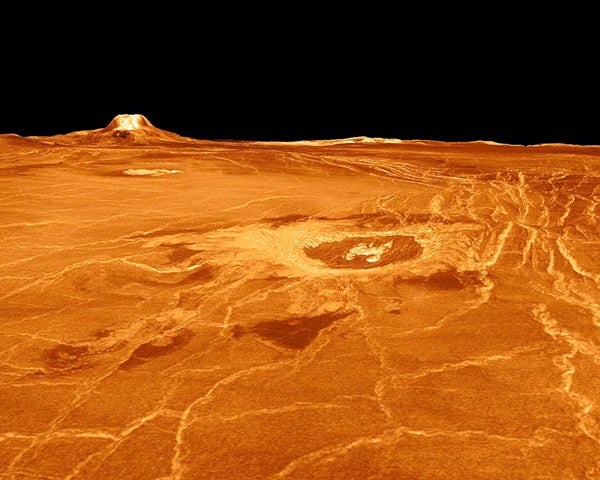

But there, the lightning and thunder never bring rain. At least, not a rain consisting of water drops. Something weird falls or condenses out of those 60-mile-thick (100 kilometers) clouds. In 1995, the Magellan spacecraft spotted a freshly deposited white coating on Venus’ mountains. It looked like snow, but, of course, it couldn’t have been. Something vaporous must have been transported upward from the surface and then condensed on those peaks. It created a pretty scene, not unlike the Colorado Rockies, but what could it be? The best guess is either the element tellurium or lead sulfide, also known as galena. For the venusian holidays, everyone sings: “I’m dreaming of a white nightmare.”

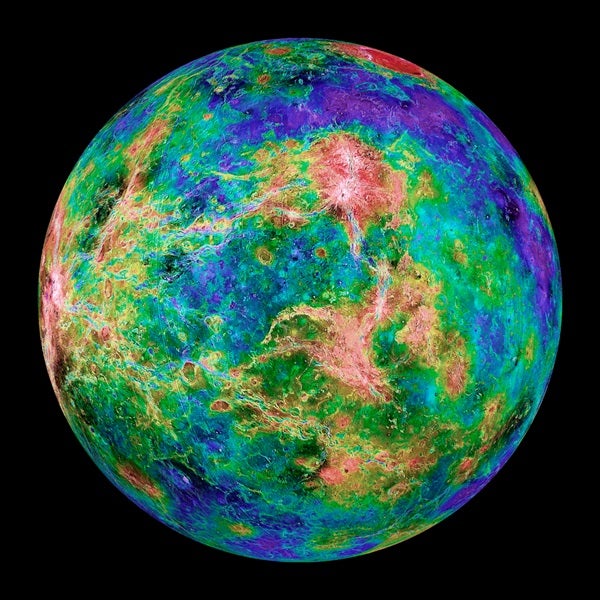

The surface of Venus is strange in other ways, too. Absent are small craters, which doesn’t surprise anyone; it would be tough for meteoroids to penetrate that thick carbon dioxide atmosphere without burning up. Only large ones manage to get through the soupy air. What’s odd is that all 1,000 of these craters look fresh, meaning that Venus’ surface shows no signs of great age. Apparently, the planet had a complete surface makeover about 500 million years ago, around the time of Earth’s “Cambrian explosion” when multicellular life first appeared here.

Earth’s surface remakes itself constantly, with plate boundaries pulling real estate into the magma below, while new lands and mountains uplift from the clashes of other tectonic plates. Few of our surface features survive more than 100 million years. But on Venus, everything apparently stays the same until pressure builds up and then gets released by a global conflagration. Like a suddenly inspired landlord, the entire surface is replaced at once.

Meanwhile, hovering high atop the dense, scorching carbon dioxide air, the lightning, and the possible liquid-lead deposits float clouds of concentrated sulfuric acid. Their brilliant tiny droplets, which would burn human skin and dissolve clothing, are what reflect sunlight so brightly.

The result is an odd disconnect between appearance and reality. From afar, people have always gazed admiringly at the shadow-casting dazzle of that “world next door.” The Maya were not alone in their Venus obsession and fashioning calendars to track its 19.5-month cycle from evening to morning star and back again. Ancient Greeks and Romans called it the “Goddess of Love.”

How poetic and appropriate that humans named the brightest “star” in their sky after love. Also touching is its longstanding moniker as our “sister planet.” But this is a hands-off relationship. Like the Mona Lisa, this is a peculiar beauty we can admire but never touch.