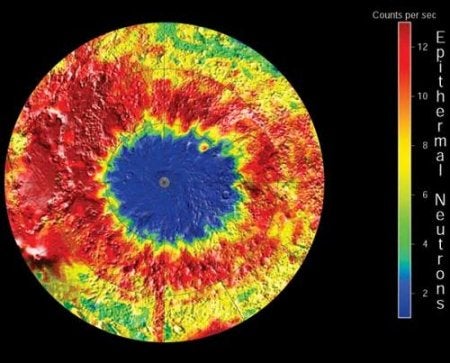

Unlike any previous or planned Mars mission, the probe was to touch down at the planet’s south pole. A tenth of the size of its northern counterpart, the south pole’s permanent cap is thought to be mostly carbon dioxide and possibly water. A seasonal cap expands on the south pole during the winter, when Mars is at its furthest point from the sun. With the fluctuating caps and suspected atypically layered terrain, this was an optimum location to survey martian climate and search for water.

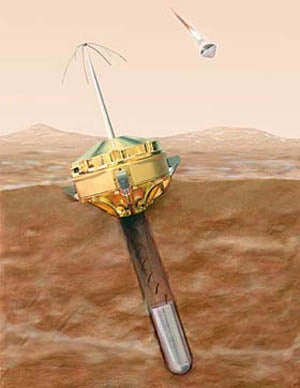

Approximately 10 minutes before landing, Mars Polar Lander was to drop two Deep Space 2 microprobes. The projectiles were to collect atmospheric data before crashing and burying themselves beneath the martian surface. Had these microprobes been successfully dropped, the instruments would have also collected and heated soil to scan for vaporized water ice.

During its final approach, Mars Polar Lander was to photograph the terrain of the south pole and surrounding areas. Continuing the imaging after the landing, the Surface Stereo Imager, using various color filters, was to capture more photographs to help determine soil types and soil composition.

While on the ground, Mars Polar Lander would have used its robotic arm to dig a hole in the terrain. The soil removed in this process would be heated and analyzed for water, like the soil collected by the microprobes. In the meantime, the probe’s camera would photograph the exposed terrain, searching for fine-scale layering.

Collaborative instruments from the Planetary Society in Pasadena and Russia’s Space Research Institute were to exercise the climatic studies. A light detection device was to determine the altitude of dust and ice clouds hanging over the lander. A small microphone on board would capture the sounds of wind gusts, blowing dust, and the spacecraft itself.

Had Mars Polar Lander survived, it would have operated for 60 to 90 days during Mars’s southern summer. Eventually the probe would have failed as it succumbed to the cold and darkness as the nights grew longer.