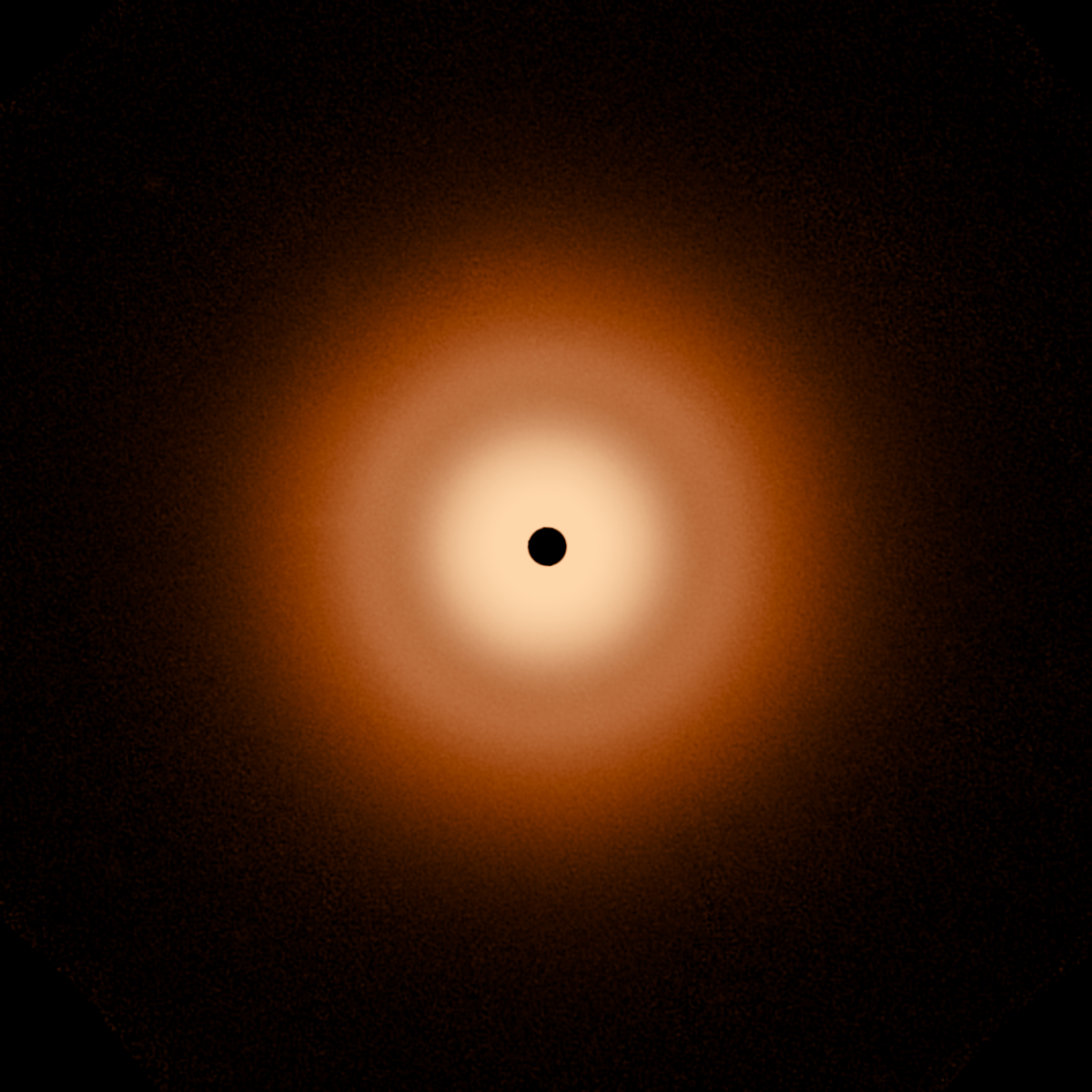

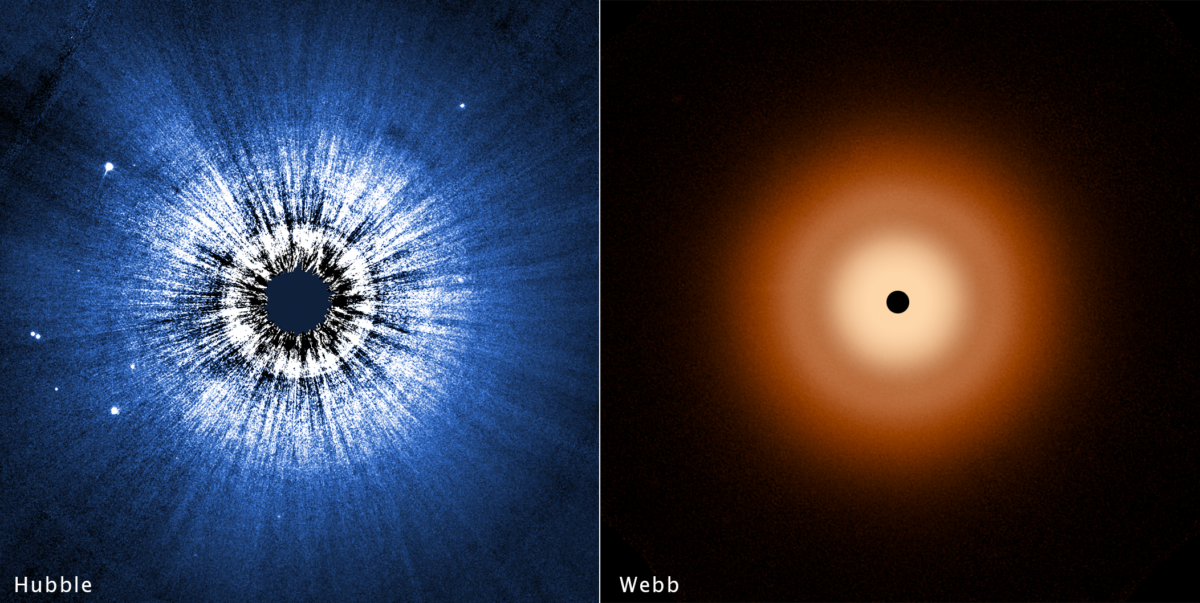

Vega, located in the constellation Lyra, is the fifth-brightest star in the night sky. It is known to be surrounded a disk of particle debris that’s almost 100 billion miles (160 billion kilometers) in diameter. The star and its orbiting disk have been photographed countless times by several observatories and satellites, although it was only recently that Vega’s disk has been captured with unprecedented clarity thanks to both the James Webb Space Telescope (JWST) and the Hubble Space Telescope.

“Between the Hubble and Webb telescopes, you get this very clear view of Vega. It’s a mysterious system because it’s unlike other circumstellar disks we’ve looked at,” said Andras Gáspár of the University of Arizona, a member of the JWST study, in a press release.

The data from JWST and Hubble allowed astronomers to observe a remarkably smooth disk with no clear signs of any planet formation — puzzling scientists as to how this could happen.

Smooth sailing

When stars are in their initial formation stages, they accrete the surrounding nebulosity and create a protoplanetary disk. As the disk forms, planets may begin to form when particles bump into each other. The clumps gradually become larger to become planetesimals (large, but not quite planets yet) and act as snowplows clearing their paths.

Well, this is the usual behavior, but Vega seems to be the exception. “The Vega disk is smooth, ridiculously smooth,” said Gáspár. And the JWST data study said it’s also “remarkably symmetric and … centered accurately on the star.”

The extremely high resolution of the image does display a faint gap within the disk, estimated to be about 60 astronomical units (AU; 1 AU is the average Earth-Sun distance of 93 million miles [150 million km]) from the star. But astronomers expected to see more.

Another star, called Fomalhaut, lies about 25 light-years away in the constellation Piscis Austrinus. The star is almost identical to Vega — in distance, temperature, and age — but the dusty disks around them couldn’t be more different. Fomalhaut’s disk contains three belts that extend out to 14 billion miles (23 billion kilometers) from its center — hinting that they were created by invisible planets.

“Given the physical similarity between the stars of Vega and Fomalhaut, why does Fomalhaut seem to have been able to form planets and Vega didn’t?” said team member George Rieke of the University of Arizona. Schuyler Wolff, the lead author of the Hubble data study added, “What’s the difference? Did the circumstellar environment, or the star itself, create that difference? What’s puzzling is that the same physics is at work in both.”

The reasoning behind such massive differences in circumstellar disk behavior between two similar stars remains a mystery for now. But the team members of both studies are determined to keep investigating and take advantage of combining JWST and Hubble data.