As Princeton University cosmologist David Spergel puts it, “The shape of the universe tells us about its past and its future.” Whether the universe will expand forever or eventually collapse, and whether it’s finite or infinite — all are questions that tie back to its shape.

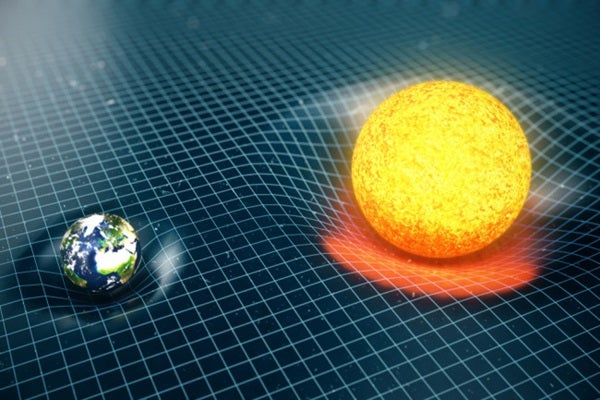

For a matter that bears on such grand questions, its components are remarkably simple. The ultimate structure of the universe depends on just two factors: its density and its rate of expansion.

Closed, open or flat universe?

Roughly 68 percent of the universe is dark energy and 27 percent is dark matter. The remainder is normal matter, which accounts for planets, stars and other bodies. The universe’s density refers to how much of this matter is packed into a given volume of space.

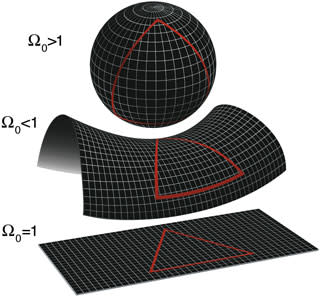

If the universe’s density is great enough for its gravity to overcome the force of expansion, then the universe will curl into a ball. This is known as the closed model, with positive curvature resembling a sphere. A mind-boggling property of this universe is that it is finite, yet it has no bounds. An intergalactic Ferdinand Magellan could circumnavigate it, traversing space forever without hitting a wall or falling over an edge.

On the other hand, if the universe’s density is low and unable to stop the expansion, space will warp in the opposite direction. This would form an open universe with negative curvature resembling a saddle.

Flat in 3D

What does a flat universe mean, though? This flatness isn’t the two-dimensional kind we often encounter in everyday life, but you can envision it with a few analogies.

Say you’re standing in one corner of a square room. Walk 10 feet along the wall to the next corner, then turn 90 degrees. Walk another 10 feet and turn 90 degrees again. Do this twice more and you’ll find yourself back where you started — you’ve completed a square. This is the standard Euclidean geometry that we all learned in high school, and if you add one more dimension you get a flat universe.

But conducting this experiment on a positively curved space that’s representative of a closed universe would create a different outcome. This time, start at Earth’s equator and walk to the North Pole. Then, turn 90 degrees and walk back to the equator. Turn 90 degrees once more and walk back to your starting point. In the flat universe example, it took four turns to get back to where you started, but only three in the closed universe example.

If you’re (understandably) still confused, here’s another example: In a flat universe, two rockets flying next to each other will always remain parallel. This is unlike a closed universe, in which the paths of these two rockets will diverge, trek along the curvature of space, and eventually loop around to meet where they started. And in a negatively curved, open universe, the rockets will separate and never cross paths again.

‘Cosmological crisis’

The best clues to the shape of the universe are embedded in the cosmic microwave background (CMB), the afterglow of the Big Bang that radiates toward us from every direction. Over the past few decades, scientists have repeatedly measured temperature fluctuations in the CMB — essentially performing trigonometry at the largest scale possible — and found almost no curvature at all.

A flat universe is a key piece of the standard cosmological model, also known as the Lambda cold dark matter (ΛCDM) model. (Λ is the Greek letter for lambda, denoting dark energy.) But, in late 2019, Alessandro Melchiorri of the Sapienza University of Rome and his colleagues published a paper concluding that CMB measurements by the Planck space observatory indicate a closed universe.

They analyzed the amount of gravitational lensing — how much the light from the CMB has been deflected by the gravity of matter in its path — and found a figure higher than predicted by the ΛCDM model. If you remove the assumption of a flat universe, instead of “trying to fit the data to the wrong model,” he says, the deviation disappears.

The Planck collaboration (of which Melchiorri is a part) also detected a lensing anomaly but didn’t find it as significant. “It’s something you can live with quite easily,” says Antony Lewis, a cosmologist at the University of Sussex in Brighton, England, and a member of the Planck team. He, like most researchers, attributes the discrepancy to a statistical fluke. “If you get a big dataset and you look for weirdnesses,” Lewis says, “you’re bound to find it.”

Melchiorri admits he’s “playing a bit of the devil’s advocate,” but he does believe scientists should remain humble and not dismiss the Planck data outright. His point isn’t that the universe is closed, per se, only that this inconsistency may be telling us something important. He also recognizes the implications of that statement. He and his co-authors deemed it a “cosmological crisis.” “Once you assume a closed universe it’s a bit of a catastrophe,” he says, “because there are many data sets that start to be in tension with [the Planck data].”

Flat as far as the eye can see

If true, it would overturn decades of astronomical findings. But aside from this data, there isn’t the slightest reason to doubt the universe is flat. All other measurements of the CMB, like those by the Atacama Cosmology Telescope (ACT) in Chile and the Wilkinson Microwave Anisotropy Probe, are consistent with flatness. Data from other sources, most notably baryon acoustic oscillations — the imprints left on galaxies from primordial sound waves that occurred after the Big Bang — also suggest flatness.

Any theory backed by such overwhelming evidence would leave most scientists skeptical of a single outlier. “The Melchiorri paper’s not ridiculous,” Spergel says, in that it really does describe a feature of the Planck data that favors positive curvature. “But,” he adds, “when you go and get more data, you see a pretty consistent picture of a flat universe.”

In a paper published in December, Spergel and dozens of other researchers associated with the ACT combined their own data and other datasets with the Planck data. They found “no evidence of deviation from flatness, supporting the interpretation that the [Planck deviation] is a statistical fluctuation.” Other analyses since the publication of Melchiorri’s paper, including one last February by University of Cambridge cosmologists George Efstathiou and Steven Gratton, have concluded the same. As far as they’re concerned, there’s no need to update the ΛCDM model.

So, at least for now, the universe seems to be a three-dimensional sheet of paper. But just as Melchiorri doesn’t insist it’s actually closed, not all scientists insist it’s actually flat — that’s just how it appears from our point of view. Our observations are, by definition, limited to the observable universe, so we could be missing something.

If the universe is curved, though, it must be so colossal that the entire 93 billion light-years we can see isn’t a large enough portion to reveal the curvature. To take an example from Earth, Gratton says, it could be as if we’re standing in a fog, unable to see beyond a small, flat patch of land — but somewhere out of sight, the horizon proves we live on a sphere. “When we say the universe is flat,” he says, “what we’re saying is, of the little bit of the universe we can see, it’s consistent with being part of a [3D analogue of a] flat surface.”