Ever since 1992, when astronomers first discovered two rocky planets orbiting a pulsar in the constellation Virgo, humans have known that other worlds exist beyond our solar system. Today, thanks to the efforts of astronomers and ambitious missions like the now-retired Kepler, we know of more than 4,000 confirmed exoplanets.

But if we can see exoplanets orbiting distant stars, that means extraterrestrial observers should be able to see Earth orbiting the Sun. Our tiny blue marble even could be on an alien astronomer’s list of rocky exoplanets capable of harboring life.

That’s a speculative scenario, of course, but it’s one astronomers still take seriously. In multiple papers over the years, they’ve identified which exoplanets would be able to spot Earth. And now, with updated information from the European Space Agency’s expansive Gaia catalog of nearby stars, two researchers have provided us with perhaps the best list yet of which alien worlds could have their eyes on us.

Observing Earth from afar

It began with a few simple questions, says Joshua Pepper, an astronomer at Lehigh University and coauthor of the recent paper, published in October in Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society.

“What if there were intelligent beings on another planet? And if they were looking at the Earth, which of those star systems could they be living in that would enable them to see Earth?” he says.

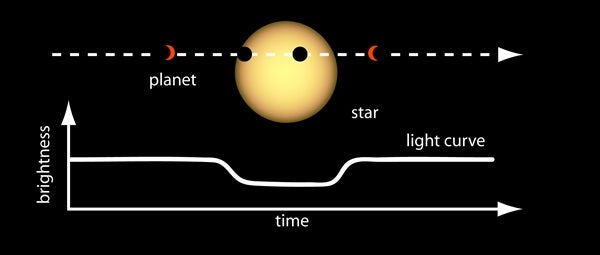

Using data from Gaia and NASA’s Transiting Exoplanet Survey Satellite (TESS), Pepper and Lisa Kaltenegger, director of the Carl Sagan Institute at Cornell University, went looking for planets that were aligned with Earth’s orbit around the Sun. This would let any alien observers witness the Sun drop in brightness a tiny bit whenever Earth passes in front of it. They cut off their search at around 330 light-years, and excluded some stars with poor data, ending up with a list of around 1,000 stars properly aligned with Earth’s orbit.

Watching a planet pass in front of its star, known as a transit, is currently the best way we have of looking for exoplanets, Pepper says. That made it a natural choice for how other planets might spot us.

So far, the researchers say they’ve identified five exoplanets that are near enough to Earth that extrasolar astronomers could theoretically see us. From those worlds, Earth would appear as a tiny blob of shadow passing in front of our Sun.

And although five exoplanets is just a tiny fraction of all the worlds out there, Pepper says their list might be a good starting point for researchers involved with the Search for Extraterrestrial Intelligence, or SETI.

“This could be a target list for SETI searches,” he says. “Any aliens on those planets would be uniquely positioned to know about the Earth.”

Earth the Exoplanet

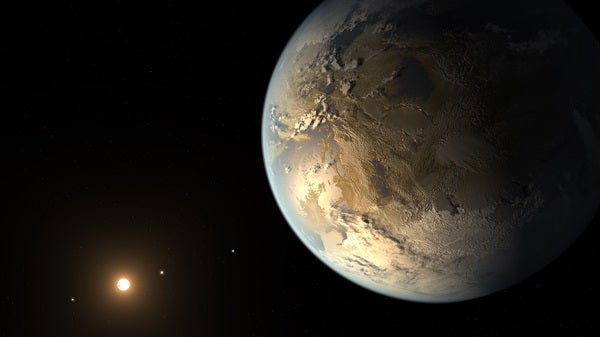

From many light-years away, Earth wouldn’t look all that impressive (barring some sort of futuristic telescope technology, of course). Anyone watching Earth as a transiting exoplanet wouldn’t see our world as a verdant oasis suffused with blue, green, and tan, as we do in up-close satellite images. They’d simply see a lump of rock getting in the way of the Sun.

But astronomers still glean plenty of information by watching exactly how a planet dims its star. They can estimate how big the world is; how quickly it orbits its star; and even the planet’s density, which tells them if it’s a gas giant like Jupiter or a rocky planet like Earth. For example, we already know this information about the five planets that Pepper and Kaltenegger think might be able to see us — they’re estimated to be super-Earths, larger than our planet but smaller than Uranus and Neptune.

As a planet passes in front of its star, astronomers also have a rare opportunity to peer into its atmosphere (if it has one). When a thin sliver of starlight passes through the world’s gaseous envelope, it picks up information about what the atmosphere is made of.

“When it emerges, that light is imprinted with the molecular signature of the gases that were in the atmosphere,” Pepper says. Using this information, astronomers are able to piece together the composition of exoplanet atmospheres. And while that’s a difficult task, the tactic offers astronomers one of the best ways of looking for life in the universe. That’s because the presence of oxygen, or other molecules unlikely to exist without biological life, would be a good sign of extraterrestrials on another world.

Earth, for example, would look pretty interesting to an alien astronomer parsing the detailed contents of our atmosphere. Relatively high levels of oxygen, methane, carbon dioxide, and other gases could serve as a strong hint that our planet teems with life.

“As far as we know, [an] atmosphere like the Earth [has], there’s really no way to mimic that without life,” Pepper says.

An even stronger sign of extraterrestrial life could come from electromagnetic signals, like the radio waves that emanate from our telecommunications equipment. Those signals are what SETI is currently looking for elsewhere in the universe.

Those efforts have yielded a couple of candidate signals over the years — though nothing approaching convincing evidence. For example, earlier this month, press reports surfaced of an intriguing signal discovered by the Breakthrough Listen project, appearing to originate from the star Proxima Centauri. However, the researchers have carefully noted that although they can’t explain the source of the signal yet, the most likely source is humanmade interference.

However, if extraterrestrials were to train an equivalent to the Green Bank Observatory on Earth, they’d see a planet abuzz with electromagnetic activity. It would be a fairly slam-dunk sign that our planet holds far more than mere rocks and water.

Another planet wouldn’t need to see Earth pass in front of the Sun to pick up our electromagnetic radiation. But Pepper says their work focuses on those planets that are most likely to find Earth. And seeing us silhouetted in front of our star is one of the best ways to do that.

Whether we want another planet to find us, of course, is another question entirely.