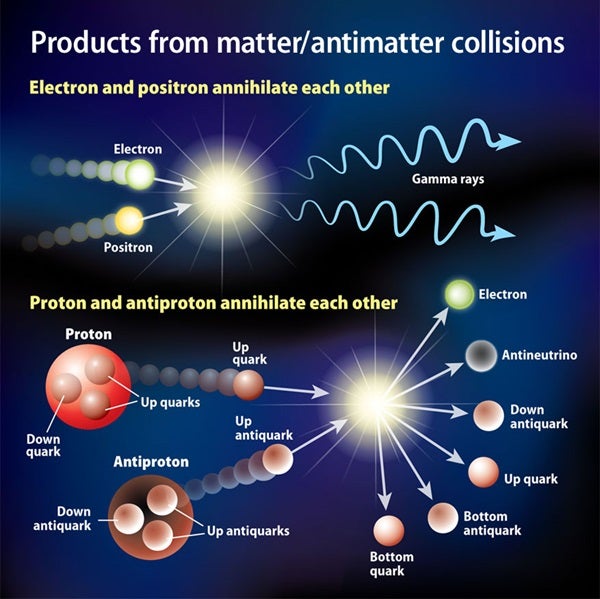

For example, when an electron meets its antiparticle — the positron — the emitted energy is most likely in the form of electromagnetic radiation. The frequency of the light from electron-positron annihilation is too high for our eyes to see, but gamma-ray detectors can identify it.

For high-energy collisions, or those between nonfundamental particles like the proton, the story is slightly more complicated. Protons are actually composed of smaller particles called quarks, so if you collide a proton and an antiproton with enough energy, you, in fact, create a quark-antiquark collision.

Electrons and quarks don’t feel just the electromagnetic force — electrons also feel the weak force while quarks feel both the weak and the strong forces. The interaction of matter and antimatter can release the energy from both of these forces in the form of exotic particles. (In fact, the much-sought-after Higgs boson is one form of weak-force energy.) However, these collisions don’t happen often because the weak and strong forces are felt at only extremely short distances while the electromagnetic force has infinite range (we see stars from billions of miles away, after all).

One way to increase the chances that a matter-antimatter collision yields non-electromagnetic energy is to accelerate the particles and antiparticles to extreme speeds and thus high energies. This happens at particle accelerators like those at Fermi National Accelerator Laboratory outside Chicago, Illinois, and the European Organization for Nuclear Research (CERN) in Geneva, Switzerland. — Patrick Fox and Adam Martin, Fermi National Accelerator Laboratory, Batavia, Illinois

When matter and antimatter annihilate each other

Thomas Hofstätter, Vienna, Austria

Matter-antimatter collisions create different products depending on the starting particles. When electrons and positrons annihilate each other, they make gamma rays. Protons are composed of quarks (and antiprotons of antiquarks), so these collisions involve more-complicated particle interactions. Astronomy: Roen Kelly

The kind of energy released during such a collision depends on which matter and antimatter particles are involved and how energetically they collide.