The universe in its infancy wasn’t the well-ordered system it is today. These days, matter clumps. Yes, into stars and asteroids, but also into much smaller units like molecules and even neutral atoms; the familiar model of a positive nucleus surrounded by orbiting electrons.

When the universe first formed however, this hierarchy didn’t yet exist. Electrons and protons flowed freely in a particle soup jostling with spare energy. It took the cosmos something like a quarter to a half million years to calm down enough for protons and electrons to pair up. Cosmologists call this era recombination, but there’s nothing “re-” about it. It was the first time ever that elementary particles joined up to form atoms.

Once they did, the pinball game stopped, and light was allowed to stream freely through the universe, which finally consisted of the empty space so prevalent today. But there was only one light present in those days: the crackle of energy from the Big Bang, already ancient but only then allowed to travel for the first time. The universe had just managed to stick together enough to form atoms, and shining stars were still eons away.

And so, after the Big Bang’s brilliance faded the universe went dark again, for something like 400 million years.

But eventually, the same processes began that reign today: atoms cooled and stopped madly churning under their own heat. Clumps formed, and then gravity took over and pulled more matter in. In those days, hydrogen and helium were very nearly the only game in town. The early universe was made of something like 75% hydrogen, 25% helium, and traces of lithium and beryllium (that is, elements one through four, for those of you looking at a table of the elements). This is talking by mass. If you want the numbers of atoms, it’s even more lopsided, because hydrogen is lighter than helium. Counting atoms instead of grams, the ratio is more like 92% hydrogen and 8% helium, with again just traces of other elements.

This means that the earliest stars were very pure. What’s more, only these elements, drifting around in gas form, existed at all. Larger molecules like the dust that now litters our cosmos hadn’t had time to accumulate. This makes it harder for clouds of gas to cool. That means that when hydrogen did form clumps, it took truly massive clouds to condense enough to form stars. The first stars, therefore, were leviathans. Scientists disagree about exactly how big they were. But conservative estimates put them at about 30, and much more likely 300 times the mass of our sun. More extreme estimates range up to 1,000 solar masses.

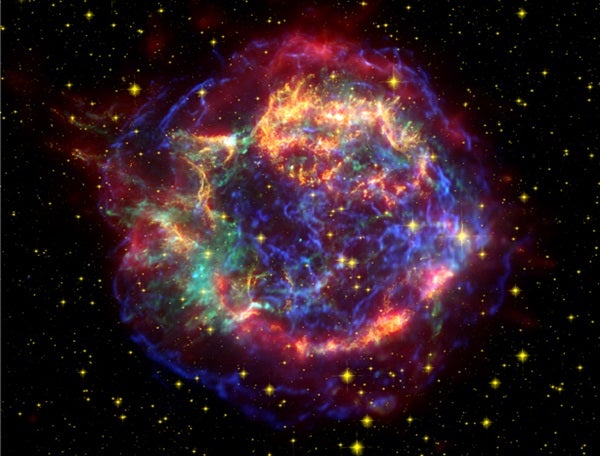

So the universe birthed enormous stars, which burned through their nearly-pure hydrogen fuel quickly, in only a few million years. Physics only requires about 100 solar masses before a star is destined to end its life as a supernova. So these behemoths definitely exploded, unleashing a slew of heavy elements into the cosmos, polluting it and changing the composition of the universe forever more.

These massive stars and the black holes they created attracted more stars around them, and the first galaxies began to emerge. Stars of all sizes were born in new stellar nurseries. And the universe as we know it now finally began to appear.

This article originally appeared on discovermagazine.com.