About two decades ago, a rare book dealer called up astronomy professor Jay Pasachoff. He had found a folio with an image of the first image of an astronomical telescope on the illustration facing the title page. He asked Pasachoff if he would be interested.

Pasachoff, an astronomer at Williams College in Massachusetts, has a longstanding interest in the foundation of astronomy. In the 1970s, he used the money earned by the successful sale of a popular astronomy textbook to purchase a book by Galileo. Over the years, his collection of rare books has grown to include texts by the historical astronomers Copernicus, Kepler, and Newton. So of course he snapped up one of only a handful of copies of a book at the heart of one of the most vitriolic confrontations in the history of astronomy.

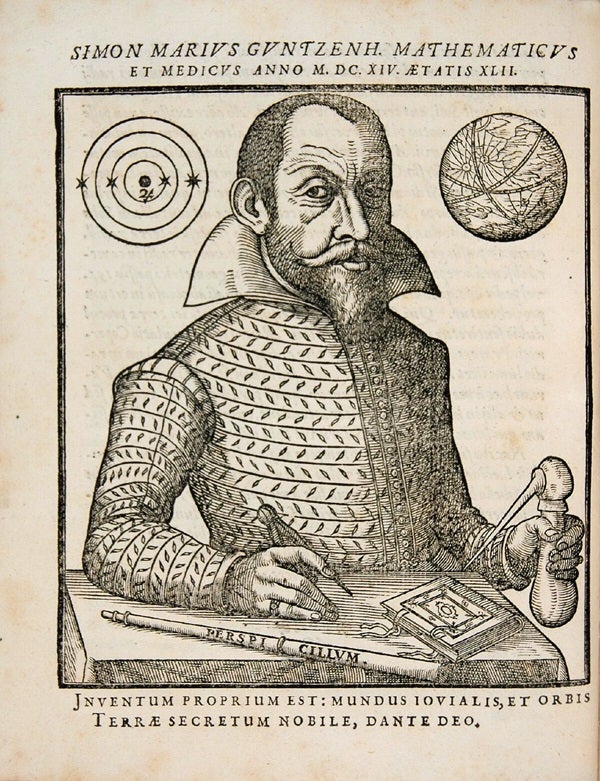

The court astronomer in Ansbach, Germany, Simon Marius began writing down his notes of three unusual objects near the planet Jupiter at the end of December 1609; a fourth appeared a few days later. He published his observations in 1611 in a 1612 almanac suffering from a small circulation. In 1614, he published his Mundus Iovialis, the book that included the first image of an astronomical telescope and the first printed display of the orbits of the Jovian moons.

Marius’ book drew immediate outcry from the famed astronomer Galileo Galilei. In early January 1610, Galileo made his first notes tracking the satellites. Like Marius, he initially spotted only three, with the fourth apparent after several days. Unlike Marius, Galileo rushed to publish his findings, with his book Siderius Nuncius submitted to the printer in 1610. He had already been recognized as the discoverer of what would be known as the Galilean moons, a discovery which was key in unraveling belief in the heliocentric version of the universe, in which everything revolved around the sun.

According to his text, Marius was not looking to diminish Galileo’s discovery. In an arguably passive-aggressive discussion in his publication, he wrote:

This is the exact truth … In recounting all this, I am not to be understood as wishing to lessen Galileo’s reputation, or to snatch from him the discovery of these Jovian stars among his countrymen in Italy – far from it. My object rather is, that it may be understood that these stars were not shown to me by any mortal in any way, but were discovered and observed by me, by my own investigation, in Germany, almost at the very time, or slightly before it, at which Galileo first saw them in Italy. The credit, therefore, of the first discovery of these stars in Italy is deservedly assigned to Galileo and remains his.

Galileo’s response to Marius’ work was to decry his fellow astronomer as a liar, a plagiarizer, and a heretic, a serious crime for the time. Marius had never observed the moons but instead had copied Galileo’s own work.

“This dominated Marius’ reputation for hundreds of years,” Pasachoff said.

New Beginnings

It wasn’t until the early 20th century that a Dutch panel of experts cleared the German astronomer of plagiarism, pointing out that Marius had made observations of the moons not contained in Galileo’s initial discovery.

The issue of the discovery came down to one of timing. It turns out that Galileo and Marius operated on two different calendars. While Catholic countries, including Italy, had made the changeover to the Gregorian Calendar in 1582, Germany remained on the Julian calendar until 1700. The two calendars operated with a difference of 10 days. The result? Marius wrote down his observations of the moons only one day after Galileo.

That doesn’t mean he wasn’t the first to see them. In his book, Marius said that he first observed the strange stars around Jupiter around the end of November. If that’s the case, his failure to write down his observations means that Galileo gets to keep the title of discoverer.

“If Marius really had been watching for awhile, he might well have seen these things before Galileo did,” Pasachoff said. “But by the dates that we have for writing things down, Galileo was first by a day.”

Unlike Galileo, however, Marius provided detailed tables of his observations, part of what helped clear him to the Dutch panel. And on the cover of the Mundo Iovialis, Marius sketched the objects in orbit, a contrast to Galileo’s sketch using asterisks and the letter O, making what Pasachoff says was “arguably the first image of the orbits.”

Mundo Iovialis also boasts the first image of an astronomical telescope, labeled ‘perspicillum’. Pasachoff says he has never heard anyone debate that Marius captured this first, though he has not extensively researched the subject.

Pasachoff asked his colleague Albert Van Helden of Rice University (Houston, Texas), now living in Holland, an expert on historical telescopes, to try to determine if the telescope in the image would have been capable of identifying the four major moons of Jupiter. He presented their results at the Division of Planetary Sciences conference in Pasadena, California in October.

According to Pasachoff, Helden has yet to find evidence that telescopes good enough to show Jupiter’s moons were produced in the Netherlands when Marius made his discovery. The German astronomer alluded to the owner of his borrowed instrument had received lenses made in Venice, where Galileo’s observations could not be confirmed until the summer of 1610.

“We have not been able to determine that the telescope shown in the carving would be able to identify the moons,” Pasachoff says.

While Marius’ name may have been lost to most students of historical astronomy, his work hasn’t completely disappeared. The four major moons of Jupiter bear the names he identified them with in Mundus Iovialis—Europa, Io, Ganymede and Callisto.

“Certainly Marius’ name deserves to be better known than it is,” Pasachoff says. “But he does have a crater on the moon named after him, so that’s not bad.”