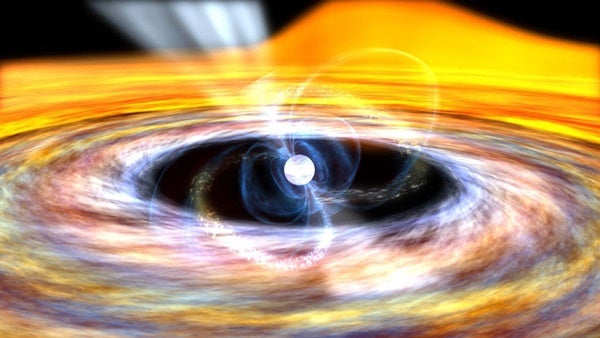

The answer lies completely in the instrumentation we use. Millisecond pulsars emit beams of electromagnetic radiation as they rotate, much like lighthouses do here on Earth. The beams themselves — typically radio waves or sometimes X-rays or gamma rays — are quite narrow and last only a small fraction of one rotation. So, in principle, they really should look like pulses.

In the case of sound, our ears and minds blend those pulses together so that we perceive a tone in the same way that we hear a note and not individual vibrations of a violin string when it is played. Our eyes and minds work similarly slow and blur things out. The fastest pulsars that we could actually see pulsing (assuming they gave off optical light!) would rotate about 30 times per second — any faster and we would perceive the pulsar as simply being on all the time. The Crab Pulsar spins about 30 times per second, and some people have reported seeing it as a star that flickers in a strange way.

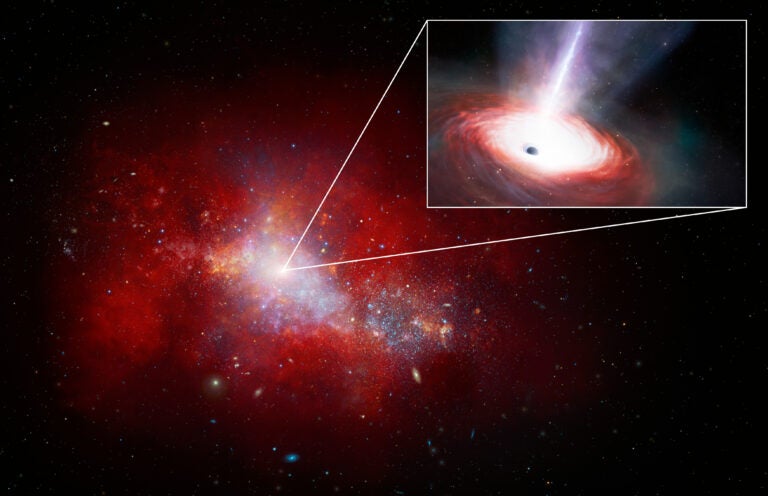

For scientific observations of pulsars, our instruments are specially designed to be much faster than human senses. We easily could detect the individual pulses from pulsars spinning more than a thousand times per second, assuming that the pulses were bright enough and that such rapidly rotating pulsars even exist (something I would love to prove with my own research).

National Radio Astronomy Observatory, Charlottesville, Virginia