In January 1774, Captain James Cook’s third and final attempt to sail south in search of the elusive Terra Australis was blocked by impenetrable sea ice. A frustrated Cook left the question of a southern land mass unanswered and later wrote, “If any one should have resolution and perseverance to clear up this point by proceeding farther than I have done, I shall not envy him the honour of the discovery; but I will be bold to say, that the world will not be benefited by it,” in a journal entry.

Despite Cook’s belief that Terra Australis wouldn’t serve any purpose to humanity, explorers did not yield. Half a century later, Russian naval officer Fabian von Bellingshausen and British Royal Navy officer Edward Bransfield independently made the first recorded sightings of the continent in January 1820. And in the early 20th century, three legendary figures — Irish explorer Ernest Shackleton, British Royal Navy officer Robert Falcon Scott, and Norwegian explorer Roald Amundsen — finally embarked on perilous missions to conquer the last great frontier.

Those earliest explorers did much in their first forays. They charted sizable areas of the frozen wilderness, took systematic meteorological observations, made significant contributions to the understanding of glaciers and ice sheets, revealed the unique adaptations of the indigenous marine species, discovered the southern magnetic pole, and finally reached the South Pole itself. One of the most astonishing discoveries was evidence from fossils that Antarctica had once been part of the ancient supercontinent Gondwana — a warm and ice-free terrain, teeming with life.

The explorers’ journeys not only pushed the boundaries of human endurance, but reaffirmed the icy continent’s unforgiving nature, and its apparent dearth of opportunities for exploitation, just as Cook had predicted. What they didn’t know was that Antarctica is in fact incredibly valuable — as a cornerstone of Earth’s climate.

Recognizing Antarctic tundra

Antarctica remained largely overlooked for another half-century, until it once again became of interest during the International Geophysical Year (IGY), from July 1957 to December 1958. The establishment of research stations in Antarctica and first crossing of the continent by the Commonwealth Trans-Antarctic Expedition (TAE) captured public attention.

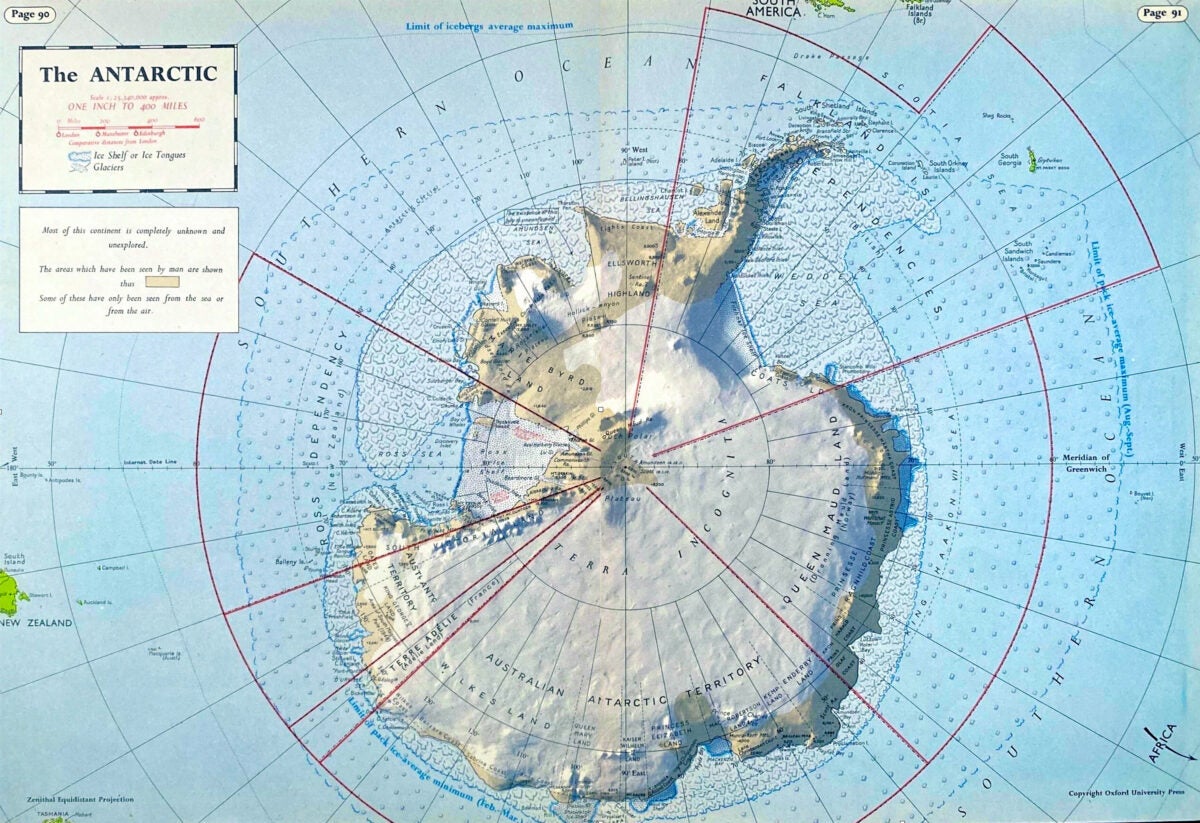

I recall being fascinated by the accounts of the TAE’s derring-do and the dramatic images of the difficulties they encountered (see page 42) at a young age. I also remember my 1956 Oxford School Atlas’ Antarctic map, accompanied by the text: “Most of this Continent is completely unknown and unexplored,” reinforcing its status as a zone of mystery and inspiring me to pursue the research of climate science.

What I was unaware of at the time were the enormous strides in scientific knowledge and understanding being harvested. These included extensive surveying and mapping, such as seismic and radar studies, glaciology, ice core drilling, atmospheric research, and oceanography. Antarctica was shown to be a single continent with a dynamic and mobile ice sheet cover much thicker than previously thought, reaching depths up to 15,000 feet (4,800 meters)! The continent and Southern Ocean emerged as key components of the global climate system — particularly their influence on the atmospheric circulation, ocean currents, and sea levels.

The data gathered during the IGY laid the foundation for the wide-ranging studies that followed, and marked the beginning of Antarctica’s transformation into a vital platform for global scientific research. IGY also demonstrated the effectiveness of international scientific collaboration and promoted science as a diplomatic tool, which was of great importance during the Cold War era. One of IGY’s most enduring legacies was the establishment of the Antarctic Treaty in 1959, which designated Antarctica as a continent for peaceful scientific exploration. The Antarctic Treaty Parties govern Antarctica and the region below 60° south latitude, coordinate international research activities in the region, and provide scientific advice to guide legislation.

In the seven decades since the IGY, Antarctic research has grown into a major multinational endeavor, despite the costs and complexities of operating with long supply chains in such a vast, hazardous, and challenging environment. The number of research stations has increased from 19 to about 70, with approximately 30 operating year-round. During the Antarctic summer (from October to March), conditions are more favorable, accessibility is easier, and the population of scientists and support staff — supported by about 30 nations — can exceed 4,000. This number drops to less than 1,000 during the winter months, when conditions are severe and only essential staff remain.

Additionally, for about the past 40 years, the region has been probed by an ever-expanding fleet of orbiting satellites, carrying sophisticated gravimeters, high-resolution optical and radar imaging instruments, altimeters, and passive microwave sensors. They map the gravity, topography, and dynamic behavior of the ice sheet and its surrounding floating ice shelves, as well as sea ice cover and oceanic behavior. The view from space is powerful, since it can achieve a spatial and temporal coverage unachievable from the ground or even from aircraft and balloons. Microwave sensors are unaffected by clouds or daylight, operating in all weather and through the long polar night.

Why study Antarctica?

My interest in the southernmost continent catalyzed in 1982, when I was asked to lead a study for the European Space Agency (ESA) on the use of spaceborne radar altimeters to study polar ice. Since then, I’ve realized that there are four main reasons why Antarctica is of deep scientific interest.

First, studies of Antarctica have made significant contributions to our understanding of Earth’s geological history — particularly regarding tectonic movements, the supercontinent cycle, and crucial mass extinction events like that marked by the Cretaceous-Paleogene (K-Pg; formerly known as K-T) boundary.

Second, Antarctica’s extreme and isolated conditions offer a unique environment for studying evolutionary adaptations. Investigating the specialized metabolic pathways and enzymes developed by Antarctic microbes to survive subzero temperatures contributes to research on biochemical survival mechanisms. For example, organisms like the extremophiles that thrive in freezing temperatures and at high salinity help us better understand life on Earth and provide insights for astrobiologists.

Third, Antarctica is an excellent place to find meteorites — more than 60 percent of the current research collections originate from there. After falling onto the ice sheet, these space rocks can be preserved for thousands or even millions of years. As the ice flows toward the continent’s edges, it transports them and ultimately creates areas where meteorites are concentrated, trapped by the landscape. When the ice sublimates or is eroded by wind, it exposes specimens on the surface, making them easy to spot. These meteorites often contain ancient materials that predate Earth, providing clues to how the planets formed and the conditions of the nebula that created the solar system.

Last, due to its location near Earth’s magnetic South Pole, Antarctica provides an ideal platform for studying the ionosphere and magnetosphere, with the goal of understanding how solar winds and charged particles interact with the magnetic field. Solar storms and geomagnetic activity can disrupt power grids, communication systems, and GPS services. The region’s isolation from human-made interference, combined with the long polar nights, offer a clear and stable environment for long-term studies of both the polar atmosphere and space weather.

Global impacts

Decades of study have demonstrated that Antarctica holds a treasure trove of scientific knowledge, contradicting Captain Cook’s gloomy prediction — a poignant irony for an individual who dedicated his life to exploration and expanding the limits of human knowledge. However, it is in the field of climatology where Antarctica truly stands out — and where its role, significance, and value become fully apparent.

The Antarctic ice sheet and the surrounding ice-covered ocean are vital parts of Earth’s climate system, influencing its atmosphere, ocean, land, ice, and biological processes. The bright surface of the ice reflects a large amount of solar radiation, resulting in both local and global cooling. The continent’s cold temperatures also maintain a strong polar vortex, which stabilizes the jet stream and keeps cold polar air from spreading to midlatitudes.

During the summer, Antarctic sea ice is limited to coastal areas, but in winter, it expands dramatically, reaching as far north as 60° south or beyond. Sea ice acts as an insulator, preventing the exchange of heat, moisture, and momentum between the ocean and atmosphere.

Antarctic bottom water, which forms under sea ice and beneath ice shelves, is one of the densest water masses on the planet. It drives global ocean circulation and interacts with some 40 percent of the world’s ocean — extending to around 50° north in the Atlantic Ocean. Cold, nutrient-rich surface waters in the Southern Ocean support phytoplankton, which take in carbon dioxide and play a role in sequestering carbon in the deep ocean.

The Antarctic ice sheet itself holds about 60 percent of the world’s freshwater. If it were to melt, global sea levels would rise by nearly 200 feet (58 m), devastating coastal communities worldwide. The floating ice shelves around its periphery help stabilize the ice sheet, modulating its contribution to sea level rise.

Through these avenues of influence, Antarctica acts as Earth’s “air conditioner,” stabilizing global temperatures through its reflective ice, cold ocean currents, and impact on atmospheric circulation. These processes help moderate global warming and maintain climate balance globally, making Antarctica a keystone of Earth’s climate system.

So, what can our global air conditioner tell us about the state of that climate system?

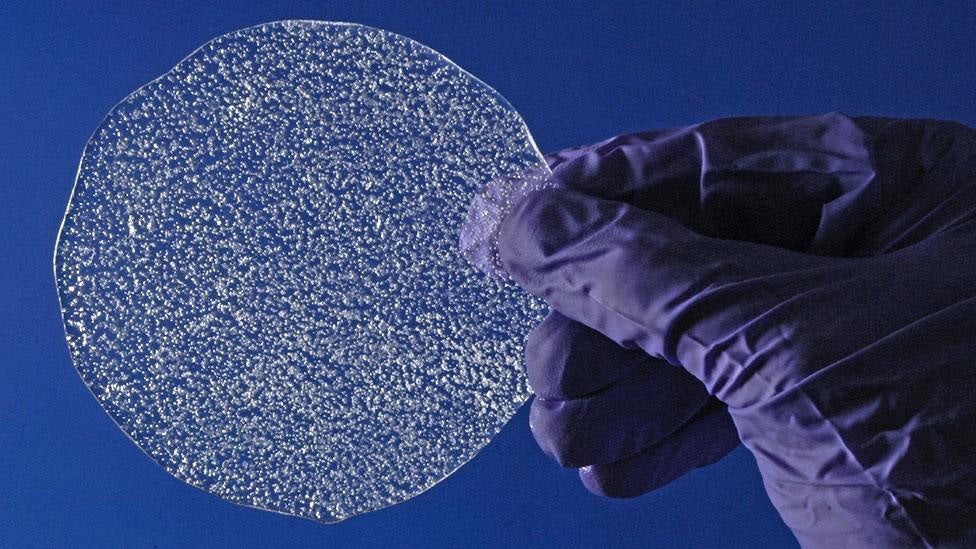

Snow layers compact into ice over time, trapping air bubbles that preserve samples of past atmospheres. By drilling deep into the ice and then analyzing the chemical and isotopic content of the extracted cores, scientists can track historical temperature changes and greenhouse gas concentrations. This research has revealed a close link between temperature, greenhouse gas levels, and ice sheet changes, all driven by astronomical cycles, marking one of the most significant geophysical discoveries of our time.

A key finding is that carbon dioxide levels in the atmosphere have never exceeded 300 parts per million (ppm; meaning the number of carbon dioxide molecules per million molecules of dry air) during the last 800,000 years. Today, carbon dioxide levels are at 427 ppm (see page 39), primarily as a result of burning fossil fuels. This is critical evidence that human activities have clearly altered the chemistry and physics of the atmosphere. In doing so we have upset the planetary energy balance, which in turn is driving global climate change as well as having impacts on Antarctica.

Are we the bad guys?

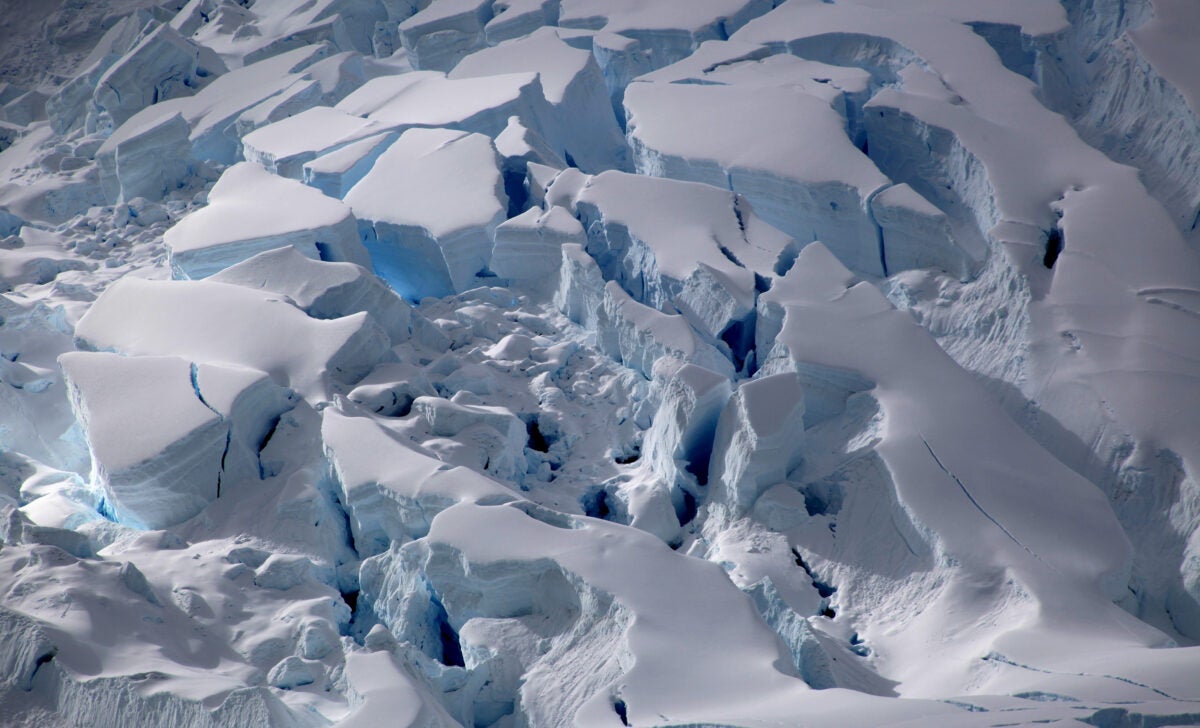

In 1978, the American glaciologist John H. Mercer described how, in a warming world, we could expect a successive collapse of ice shelves extending southward along the Antarctic Peninsula. He further warned this could be followed by accelerating ice loss in West Antarctica. Airborne radio-echo sounding surveys, which penetrate the ice to its base, have revealed that the West Antarctic Ice Sheet (WAIS) is particularly vulnerable to melting because it rests on bedrock below sea level. Salt lowers the freezing point of water, which makes the ice underwater more prone to disappearing.

Satellite and in situ data have indeed shown such successive collapse of Peninsula ice shelves and an accelerating loss of ice from the WAIS (see page 40). The latter is estimated to account for about 0.02 inch (0.4 millimeter) of the current 0.2-inch (4 mm) annual mean global sea level rise. If the WAIS was to be drained, it would cause the global sea level to rise about 10 feet (3 m).

While the seasonal extent of Antarctic sea ice had remained relatively stable or even increased slightly over the last 40 years, recent data show significant changes. Specifically, since 2016, the extent of the ice has experienced record low levels during several consecutive seasons.

The messages from collapsing Antarctic ice leaves much uncertainty about its future behavior. Both the WAIS ice flow and the Southern Ocean ice cover are potential Earth system tipping points — critical thresholds within Earth’s climate for collapse which, once triggered, cannot be stopped or reversed. Such complex systems are hard to model, and they have the capacity for surprises. Even so, there is a strong likelihood that the climate system we are creating will be significantly less amenable to human wellbeing than the one we inherited.

Have we inadvertently launched Antarctica on a path that could ultimately return it to a state of warmth, devoid of ice? UN Secretary General António Guterres characterizes our predicament as an alarming “code red.”

Now’s our chance to step up

So, how can these alarming signals from the Antarctic be turned into meaningful action? Tackling climate change requires a dual approach: reducing the magnitude and severity of change, whilst adapting to its ineluctable consequences. The top priority is to cut greenhouse gas emissions by transitioning to renewable energy, improving energy efficiency, halting deforestation, restoring ecosystems, and adopting sustainable agriculture.

Simultaneously, adaptation involves building resilience through measures such as climate-toughened infrastructure, safeguarding vulnerable communities, enhancing water and food security, and investing in early-warning systems for extreme weather events. However, progress is hindered by the inertia of our modern systems and powerful forces resisting change. Traditional approaches, such as the slow and laborious UN Climate Change Conferences, are proving insufficient.

Nonetheless, strong narratives and examples of success are emerging as robust tools to shift behaviors. Motivated citizens and institutions — such as businesses, cities, regions, and even ad hoc national coalitions — are stepping up to drive transformative change and accelerate the momentum toward a sustainable future.

How does Antarctica fit into this potential equation? To the average world citizen, busy with their daily lives, the realm of the Antarctic seems distant, exotic, and disconnected. Even a senior minister I recently briefed admitted that he had been ignorant of its location; he pointed out that on his children’s globe, Antarctica was covered by the manufacturer’s label. This detachment underscores the challenge of making Antarctica’s key role in Earth’s climate system resonate with the global public.

Yet, one possibility is emerging — and from an unlikely quarter. In recent years, Antarctic tourism has seen significant growth. The number of tourists visiting the continent has increased dramatically, rising in three decades from just over 5,000 visitors per season to more than 100,000. This surge reflects a growing global interest in the unique environment of Antarctica. Further, because it is a costly destination, many of these visitors — who naturally require the means to travel there — may be influential. Perhaps their experience of its majesty and fragility will increasingly permeate global awareness, catalyzing humanity to accelerate the scale and pace of actions to both moderate our influence on and adapt to our changing climate system.

For my own part, having visited the frozen continent many times, my abiding memory is of an albatross, effortlessly skimming the ocean waves as it rode the slipstream of a cruising research vessel — perfectly adapted to this harsh and unforgiving domain. It would be a tragedy of cosmic proportions if such perfection were to be lost through our negligence.