Cassini intentionally crashed into Saturn to prevent contamination from earthly organisms, but wouldn’t Huygens pose a much greater risk, as it actually landed on Titan?

Rich Andreano

Lakewood, Colorado

The rationale dominating the decisions to land Huygens on Titan and destroy Cassini in Saturn’s atmosphere is that astrobiologists and planetary protection experts are far more concerned about contaminating Enceladus than about contaminating Titan.

This might seem counterintuitive: Titan is of major astrobiological import because its surface and atmosphere are teeming with organic chemicals — including many that are part of the basis of life on Earth and which we think played a role in the origin of life. Titan is also unique as a moon with a substantial atmosphere.

However, due to Titan’s cold temperatures (minus 290 degrees Fahrenheit, or minus 179 degrees Celsius), we expect its organic chemicals have not evolved into biology, or at least not Earth-like biology. On Earth, biological reactions depend on water being in a liquid state to act as a solvent via hydrogen bonding, allowing organic molecules to form membranes and thus cells.

While ammonia could be the solvent and the basis for membranes on a super-cold world like Titan, ESA considered the risk of contaminating such a cold biosphere to be extremely low. The agency states on its website: “The harsh environment is expected to kill microorganisms that may have hitchhiked from Earth on board the clean space probe.”

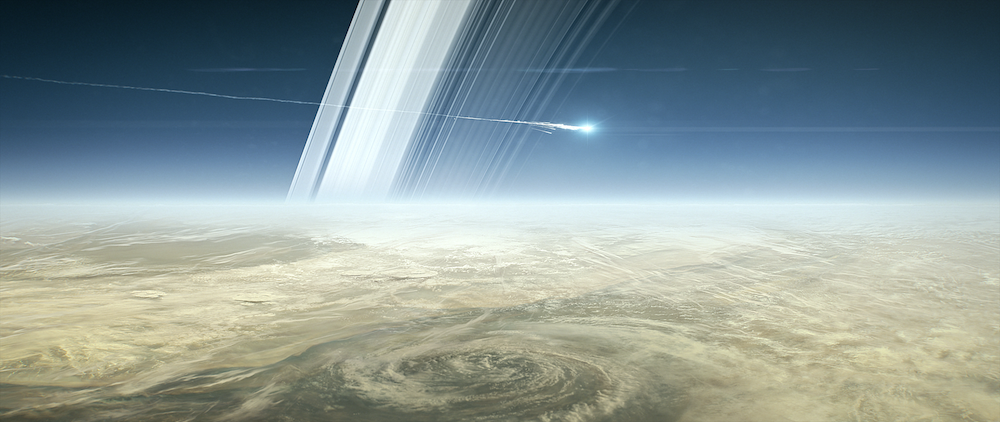

In contrast, Enceladus harbors a worldwide ocean of liquid water under a layer of surface ice, making this moon possibly the most important spot in the solar system to look for extant (Earth-like) extraterrestrial microorganisms. Consequently, the NASA-ESA team wanted to eliminate any chance of Earth hardware crashing onto Enceladus, and thus crashed Cassini into Saturn’s atmosphere.

David Warmflash

Astrobiologist and Science Communicator, Portland, Oregon