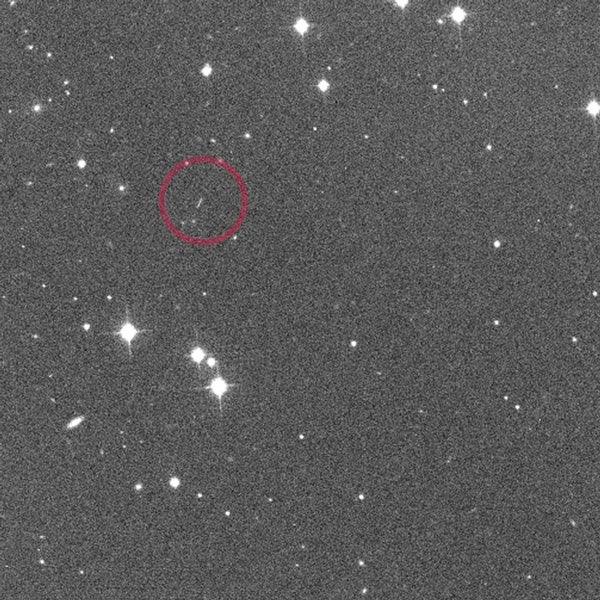

“It keeps well away from Earth,” said Apostolos “Tolis” Christou, who, together with David Asher from the Armagh Observatory in Northern Ireland, analyzed the orbit of the body after it was discovered in infrared images taken by WISE. “So well, in fact, that it has likely been in this orbit for several hundred thousand years, never coming closer to our planet than 50 times the distance to the Moon.”

The asteroid is one of a few that traces out a horseshoe shape relative to Earth. As the asteroid approaches Earth, the planet’s gravity causes the object to shift back into a larger orbit that takes longer to go around the Sun than Earth. Alternately, as Earth catches up with the asteroid, the planet’s gravity causes it to fall into a closer orbit that takes less time to go around the Sun than Earth. The asteroid therefore never completely passes our planet. This slingshot-like effect results in a horseshoe-shaped path as seen from Earth in which 2010 SO16 takes 175 years to get from one end of the horseshoe to the other.

“The origins of this object could prove to be very interesting,” said Amy Mainzer from NASA’s Jet Propulsion Laboratory in Pasadena, California. “We are really excited that the astronomy community is already finding treasures in the NEOWISE data that have been released so far.”

NEOWISE finished its one complete sweep of the solar system in early February of this year. Data on the orbits of asteroids and comets detected by the project, including near-Earth objects, are cataloged at the NASA-funded International Astronomical Union’s Minor Planet Center at the Smithsonian Astrophysical Observatory in Cambridge, Massachusetts.

“It keeps well away from Earth,” said Apostolos “Tolis” Christou, who, together with David Asher from the Armagh Observatory in Northern Ireland, analyzed the orbit of the body after it was discovered in infrared images taken by WISE. “So well, in fact, that it has likely been in this orbit for several hundred thousand years, never coming closer to our planet than 50 times the distance to the Moon.”

The asteroid is one of a few that traces out a horseshoe shape relative to Earth. As the asteroid approaches Earth, the planet’s gravity causes the object to shift back into a larger orbit that takes longer to go around the Sun than Earth. Alternately, as Earth catches up with the asteroid, the planet’s gravity causes it to fall into a closer orbit that takes less time to go around the Sun than Earth. The asteroid therefore never completely passes our planet. This slingshot-like effect results in a horseshoe-shaped path as seen from Earth in which 2010 SO16 takes 175 years to get from one end of the horseshoe to the other.

“The origins of this object could prove to be very interesting,” said Amy Mainzer from NASA’s Jet Propulsion Laboratory in Pasadena, California. “We are really excited that the astronomy community is already finding treasures in the NEOWISE data that have been released so far.”

NEOWISE finished its one complete sweep of the solar system in early February of this year. Data on the orbits of asteroids and comets detected by the project, including near-Earth objects, are cataloged at the NASA-funded International Astronomical Union’s Minor Planet Center at the Smithsonian Astrophysical Observatory in Cambridge, Massachusetts.