Five decades ago, the black hole at the center of our galaxy swallowed a mass equivalent to the planet Mercury. The resulting outburst was about 1,000 times brighter and lasted well over 1,000 times longer than any of the recent outbursts observed by the Chandra X-ray Observatory.

“Our data show it has been 50 years or so since the black hole had its last decent meal,” says Michael Muno at the California Institute of Technology in Pasadena. “This is nothing like the feasting that black holes in other galaxies sometimes enjoy, but it gives unique knowledge about the feeding habits of our closest supermassive black hole.”

Scientists have long known a black hole with a mass of about 3 million Suns lurks at our galaxy’s center. Evidence for the blast comes from X rays reflected off gas clouds near the giant black hole. Scientists think the outburst arose when the black hole “lunched” on a lump of matter equivalent to the mass of Mercury. “Astrophysically speaking, it’s a pretty small mass,” Muno notes.

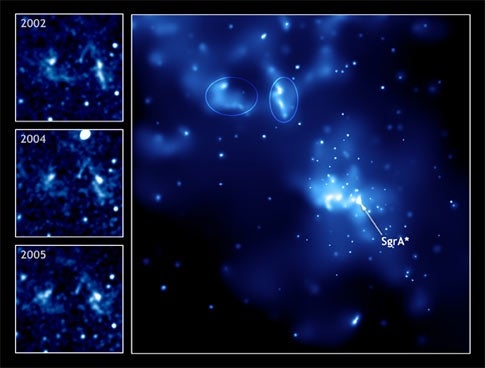

During the outburst, which may have lasted as long as 2 years, the area near the black hole would have blazed 100,000 times brighter than it is now. The X rays from the outburst continued moving through space even after the flare settled down. When this pulse of radiation reached nearby gas clouds, it illuminated them.

Theory predicts an outburst from the black hole would cause X-ray emission from the clouds to vary in both intensity and shape. Muno and his team found these changes for the first time.

The latest results corroborate other independent, but indirect, evidence for light echoes from black-hole outbursts further back in time. Muno suggests outflows from stars near the galactic center may accumulate in a disk that, every century or so, becomes unstable and dumps material into the black hole. Or perhaps the black hole “snacks” on small dust clouds that wander too close.

Present faintness of the Milky Way’s central black hole implies stars and gas rarely get swallowed. “The huge appetite is there, but it’s not being satisfied,” says co-author Frederick K. Baganoff of the Massachusetts Institute of Technology in Cambridge.

Muno presented the results January 10 at the American Astronomical Society meeting in Seattle. The findings will appear in an upcoming issue of The Astrophysical Journal Letters.