In the early 1980s, Edmund went deeper with the Mag 6 Star Atlas, written by former Astronomy editor Terence Dickinson. The maps were drawn by another Astronomy stalwart, artist Victor Costanzo. I had the honor of compiling the tables of notable deep-sky objects that faced each map.

Though I think I did a pretty good job, I made one regrettable mistake: I left out the binary star Xi (ξ) Ursae Majoris (Xi UMa). This pair has a declination of 32° north, placing it near the bottom of a circumpolar map and the top of an equatorial one. I suspect that I left it off one table, planning to add it to the other, and then left it off the other, assuming I’d placed it on the first. I didn’t discover the error until the Mag 6 Star Atlas was already in print.

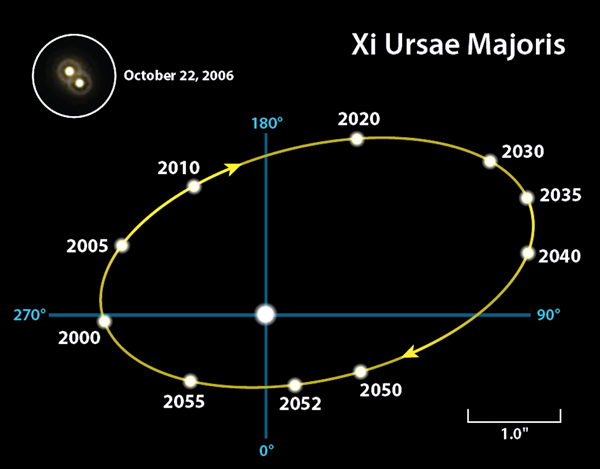

To atone for my sin, let’s shine a spotlight on this noteworthy double star. Its duplicity was discovered by William Herschel in 1780. Further observations led him to announce in 1804 that the component stars are part of a physically connected binary system, belying the general belief at the time that double stars were mere chance optical alignments of widely separated stars. In 1828, Xi UMa became the first binary star for which an orbit was calculated, a feat accomplished by the French astronomer Félix Savary. Its orbital period of just under 60 years is unusually short for a visual binary star. It also helps that Xi UMa lies slightly less than 30 light-years away.

When you peer into the eyepiece, you quickly realize why Xi UMa is among the finest double stars. Here is a near-twin match of yellowish Sol-like stars.

Separated by a mere 2″, they can be split on a night of good seeing with a magnifying power of 100x or more. Because Xi UMa has a short orbital period and the separation between the stars is increasing, the two will be even easier to resolve when they reach their greatest separation (3.1″) in just 16 years. (Refer to the orbital diagram on this page.) Right now, the fainter component, Xi UMa B, lies south-southeast (at a position angle of 160°) of the brighter main star, Xi UMa A. By 2035, its position angle will have changed nearly 50° and be to the east-southeast.

There’s more to Xi UMa than meets the eye. Spectroscopic studies reveal that each visual component is a spectroscopic binary with a red dwarf partner. One orbits Xi UMa A every 1.83 years; the other circles Xi UMa B every 3.98 days. Another red dwarf, of 15th magnitude and about 1″ from the main pair, and a 19th-magnitude T-type brown dwarf located 8.5″ away might be physically connected to this quartet as well.

It just occurred to me that I can get Xi UMa into the Mag 6 Star Atlas after all. If you own a copy, turn to the data table facing either Map 2 or 6 and add the following to the double star list:

ξ UMa 11h16m +31.8° 4.3+4.8 1.9″ 166° 2017 Binary – period 57.9 years. Separation increasing to 3.1″ in 2035. Both yellow.

The coordinates are for 1950.0, same as in the original Mag 6 Star Atlas. (The 2000.0 coordinates are 11h18m, +31.5°.) The data are from the online edition of The Washington Double Star Catalog, and the notes are mine.

The Mag 6 Star Atlas is no longer in print and used copies are rare. For a star atlas comparable in scope, I recommend Norton’s Star Atlas, a standby since it first appeared in 1910. Used copies of the 20th (2004) edition can be purchased for under $10, including shipping.

Questions, comments, or suggestions? Email me at gchaple@hotmail.com. Next month: We attack the Hydra! Clear skies!