Scientists at the European Space Agency have successfully engineered the quietest environment in the known universe, paving the way for deep-space gravitational wave detectors.

In December 2015, the 22-nation ESA launched the LISA Pathfinder spacecraft to determine if it’s possible for two gold-platinum cubes to remain perfectly still, relative to each other, as they orbited the sun. That meant shielding the cubes from all disturbances — even forces as minuscule as the gravitational pull of a mosquito — to ensure only a passing gravitational wave, and not an errant gas molecule, could squeeze the masses closer together.

In a paper published Tuesday in Physical Review Letters, ESA scientists announced that LISA Pathfinder not only proved the technology, it exceeded expectations. The test masses are falling freely through space, disturbed only by the forces of gravity, to a precision five times better than expected. Though LISA Pathfinder isn’t designed to detect gravitational waves, it proved that scientists can do it from space.

“Now, we are fully ready to jump,” said ESA’s Fabio Favata during a press conference Tuesday at the European Space Astronomy Centre in Madrid, Spain. “We have not only learned to walk, but to actually to jog pretty well. We are now ready for the big marathon.”

Space Search

Gravitational waves are fluctuations in space-time that emanate from massive cosmic events such as supernovas and black hole collisions. But the oscillations in space-time are tiny. When the ground-based Laser Interferometer Gravitational-Wave Observatory (LIGO) detected the first gravitational wave in September, the wave squeezed its 4-kilometer arms by just 1/10,000th the diameter of a proton.

Now that LISA Pathfinder is a success, ESA scientists will set their sights on building the full-scale, space-based gravitational wave detector, eLISA, which is set to launch in 2034. The detector will consist of a “mother” and two “daughter” spacecraft arranged in an equilateral triangle connected by 5-million-kilometer-long laser arms. When a wave passes by, it will squeeze those arms ever so slightly.

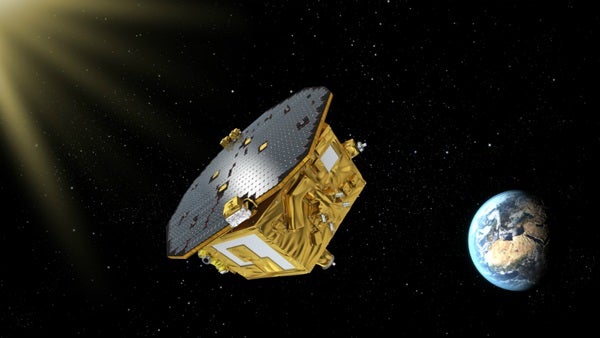

An artist’s conception of what the full eLISA gravitational wave detector will look like. (Credit: NASA)

When eLISA begins operations, it will detect gravitational wave frequencies that can’t be picked up by ground-based instruments like LIGO. Gravitational waves span a broad spectrum of frequencies — similar to the difference between visible and infrared light. Ground-based detectors like LIGO can measure higher-frequency waves, but eLISA, nestled in the stillness of space, will detect low-frequency gravitational waves produced by even more exotic events.

“Every time we open a new window to the universe, we see things that we don’t expect,” said Paul McNamara, a LISA Pathfinder project scientist.

Far From Finished

“The mission that we are celebrating today is a key step for the development of a gravitational wave observatory, but there are other technologies that aren’t there yet,” Favata said.

For example, the lasers that will connect eLISA’s 5-million-kilometer-long “arms” don’t yet exist, but scientists are already working on the problem. They’ll need to design lasers that are powerful enough to link eLISA’s components together, but won’t disrupt the instrument’s delicate alignment.

How and when everything will come together remains to be seen, and Favata said the technology will “be ready when it’s ready.” But Tuesday was a major milestone for space-based gravitational wave astronomy. Demonstrating that this is even possible is a big first step.

This post originally appeared at Discover Magazine.