When humans visit Mars later this century, they will alight on its ochre-hued sands with the same spirit of adventure and thirst for opportunity as a young girl whose essay was selected from among 10,000 online submissions to name a pair of Mars-trekking rovers.

In 2002, nine-year-old Sofi Collis, then living in Scottsdale, Arizona, entered the contest run by NASA, the Planetary Society, and toymaker Lego, which challenged students aged 5 to 18 to conceive names for the golf-cart-sized Mars Exploration Rovers. A Siberian orphan who had been adopted in the U.S. at the age of two, Collis wrote that she used to look up at the “sparkly” night sky to lift her spirits. “In America, I can make all my dreams come true. Thank you for the ‘Spirit’ and the ‘Opportunity.’”

Twin explorers

The robotic Spirit and Opportunity rose from Earth and fastened their gaze on Mars 20 summers ago. Intended to survive on the planet’s frigid, wind-whipped surface for just 90 Earth days and drive only about 0.4 mile (600 meters) atop a chassis of six cleated wheels, the twins vastly outperformed all expectations: Spirit 20 times over, Opportunity by a staggering 60.

Spirit lasted six years, roving across 4.8 miles (7.7 kilometers) of Martian terrain. But Opportunity endured some 15 years, snaring a record in 2014 for the farthest-driven vehicle on another world. By the time she fell silent, she had over 28 miles (45 km) on her odometer. And between them, this intrepid duo snapped more than 341,000 photographs.

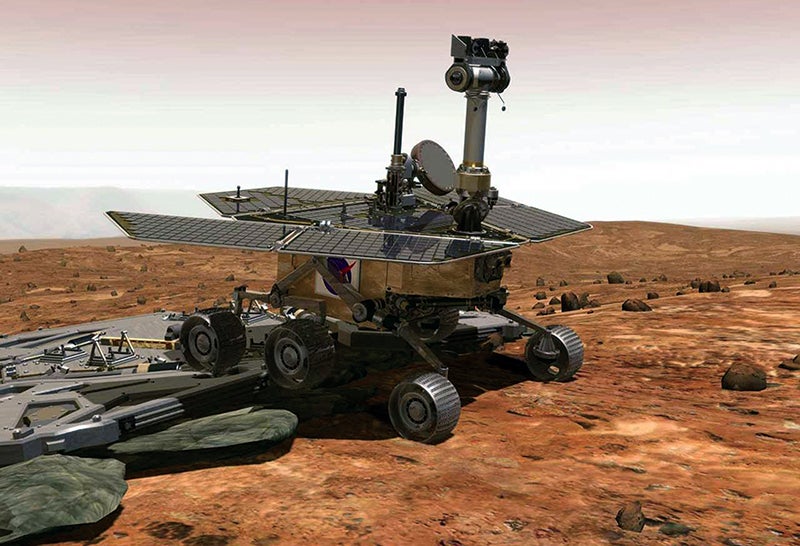

Targeting opposite hemispheres of the Red Planet, Spirit headed for the 103-mile-wide (166 km) Gusev Crater, likely formed by an asteroid impact 3.5 billion years ago and possibly the site of an ancient lake. Opportunity took aim at Meridiani Planum, a broad plain with strong chemical signatures of a wet, watery past. Together, they sought clues to Mars’ past environment and whether this modern-day cold, dry desert had ever been conducive to life. Laden with cameras, spectrometers, a rock abrasion tool for direct sampling, and their own wheels to help dig exploratory trenches in the martian dirt, the solar-powered twins were tasked with hunting minerals left behind by water-driven processes. They would also trace the geological mechanisms that shaped Mars’ now-arid landscape. Each rover weighed 408 pounds (185 kilograms), stood 5.1 feet (1.5 m) tall, and was 7.5 feet (2.3 m) wide and 5.2 feet (1.6 m) long. They inched their way across the ubiquitous red regolith at a snail’s pace, averaging just 0.02 mph (0.03 km/h).

A long journey

Launched by two Delta II Heavy rockets from adjacent Launch Complexes 17A and 17B at Florida’s Cape Canaveral Air Force Station, Spirit flew first on June 10, 2003, followed by Opportunity on July 7 (local time). Thus began a 302-million-mile (486 million km) trek to shed light on Mars’ aqueous past.

They sat snugly for their voyages inside solar-powered cruise stages, guarded against the temperature and radiation extremes of deep space. But their real close-quarters protection came from an ablative aeroshell, parachute, retrorockets and airbags that slowed them from 11,800 mph (18,900 km/h) at the point of entry into Mars’ thin atmosphere to an almost dead-stop a few tens of feet above the surface. The descent from the top of the carbon-dioxide-rich atmosphere to the ground took six minutes. Mission controllers called it their “six minutes of terror”.

Spirit reached the planet on Jan. 3, 2004, a cocoon of four six-lobed airbags cushioning the rover as it bounced up to five stories high and as far as 0.6 mile (0.96 km) across stony terrain, finally coming to a halt inside the Connecticut-sized Gusev basin. The airbags deflated, the lander’s sides opened like great mechanized petals, and, after unfurling her two solar panel “wings,” Spirit drove onto a barren, featureless plain, framed by a horizon of low hills and backlit by a lowering dull red sky.

Three weeks later, on Jan. 25, Opportunity duplicated Spirit’s feat at Meridiani Planum, which straddles Mars’ equator and might have held enough water 3.7 billion years ago to harbor river channels and even a salty sea. Opportunity’s arrival, by pure happenstance, saw her roll into a 72-foot-wide (22 m) crater, later named Eagle: an apt golfer’s term for a hole-in-one.

Picking Gusev and Meridiani required both sites to exhibit strong evidence of ancient water, but they also had to lack too many rocks that might hinder the rovers and their airbags. Mission planners needed to account for wind speeds, sloping terrain, and the prevalence of dust, as well as ensure both locales hugged the equator, receiving enough sunlight to power the twins on their travels.

A legacy of science

Soon after touching down, their respective landing sites were named for two lost space shuttle crews: Gusev became the Columbia Memorial Station and Meridiani the Challenger Memorial Station. The ridge of low hills on Spirit’s horizon was styled the Columbia Hills, its highest peak, the 269-foot (82 m) Husband Hill — which the rover summited in August 2005 — honoring Columbia’s late commander, Rick Husband.

Spirit found six distinct rock types in the hills, all showing alteration by aqueous (water-based) liquids. Some were enriched in phosphorus, sulfur, chlorine, and bromine, which are often carried in watery solutions. The discovery of goethite (a mineral that forms only in water’s presence) proved especially notable. Coatings and cracks inside rocks also hinted at water’s actions, while traces of clays, near-pure silica, and possibly an area of evaporate added to a corpus in favor of a wetter Gusev, long ago.

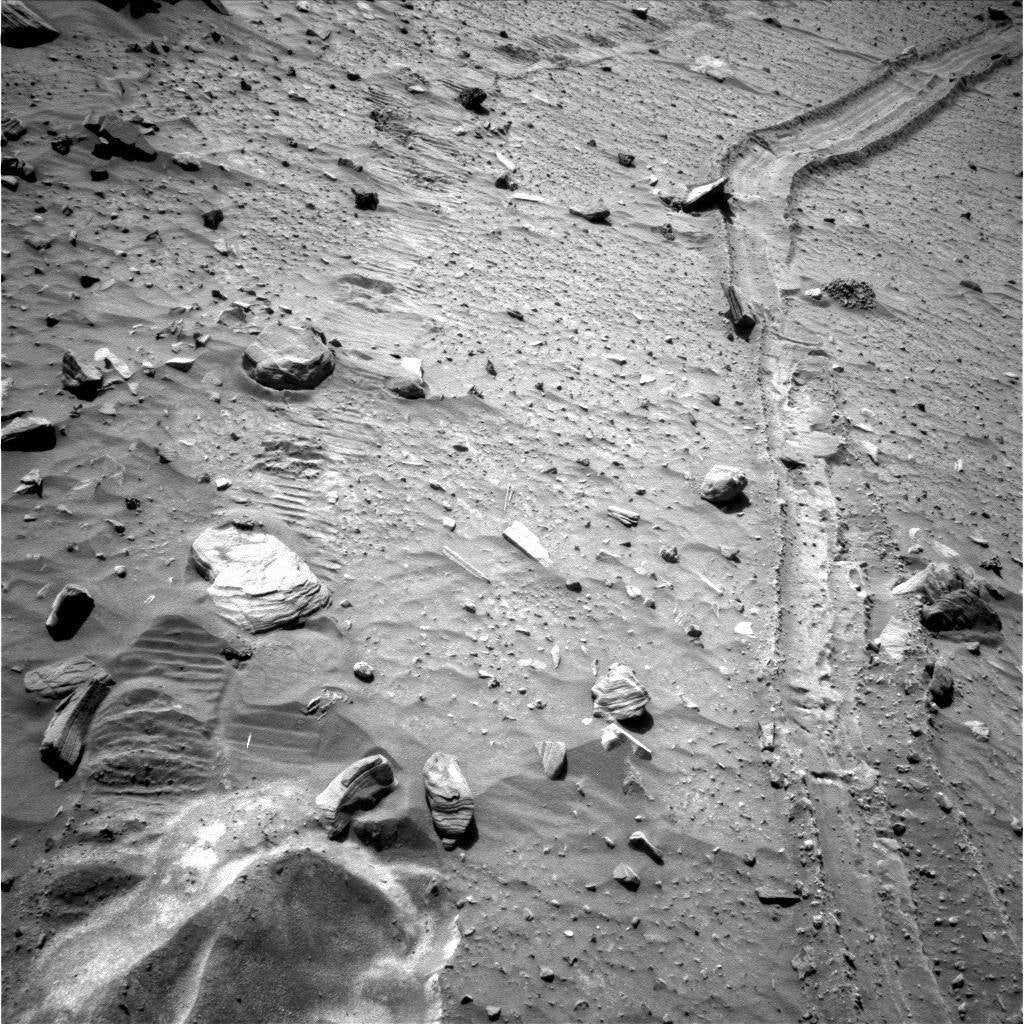

At Meridiani, Opportunity discovered deposits of grey hematite, an iron-oxide mineral usually produced in water-rich environments. It found curious spherules of the stuff (nicknamed martian blueberries), some sitting loosely on the ground, others embedded in rocks, and most measuring less than 0.2 inch (6 millimeters) across. Stratified patterns in outcrops pointed to water activity and irregular distributions of chlorine and bromine hinted at the shoreline of a long-gone salty sea.

In March 2004, Spirit acquired the first image of Earth from another planet’s surface. And in January 2005, Opportunity found the first meteorite identified on another world: the basketball-sized Heat Shield Rock. It was the first of eight iron-nickel meteorites found by the roving twins.

Trials and tribulations

Despite their successes, the duo struggled with mechanical and martian maladies: loss of wheel steering, flash memory glitches, and savage dust storms. Although one lucky encounter with a dust devil in March 2005 cleaned Spirit’s solar arrays and aided her longevity, more often, Mars’ magnetic dust — which Opportunity found contains titanomagnetite — conspired against them, forcing the rovers to hunker down into low-power hibernation.

Spirit got stuck in soft sand in May 2009, causing her wheels to lose traction. (At the time, only five of the six were working, one having given out three years earlier.) Despite efforts to free her, she was repurposed as a stationary science lab. One of her new tasks was to understand wobbles in Mars’ rotation that might indicate whether the core is solid or liquid. But on March 22, 2010, Spirit fell silent for the final time as temperatures plummeted and battery power ebbed away. In May 2011, NASA announced a transmission to the rover on the 25th would be their last attempt to rouse it; with no reply, the mission officially ended.

Her sister carried on for eight more years. But finally, she, too, succumbed. A raging planetwide storm in June 2018 blanketed Opportunity’s location and early the following year, after fruitless attempts at contact, its mission also ended. NASA’s last transmission to the old rover were the strains of “I’ll Be Seeing You” by Billie Holiday.

But perhaps at some future date, living explorers will set foot on Mars and human eyes will see these hardworking twins once again.