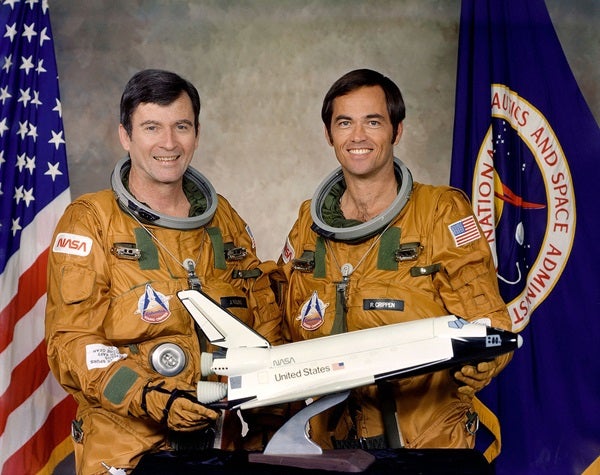

In April 1981, John Young — America’s premier astronaut and one of only 12 people to ever walk on the Moon — was training with co-pilot Bob Crippen for STS-1, the maiden voyage of space shuttle Columbia. Though eager, Young harbored no illusions that he might never return from this first mission of the Space Shuttle Program.

After rocketing into space, Columbia aimed to circle our planet 36 times over two days. But then, unlike previous spacecraft, it would glide back to Earth, landing on a runway like an airplane. NASA hoped its reusable fleet of four shuttles — Atlantis, Challenger, Discovery, and Columbia — would launch weekly with crews of up to seven, allowing more rapid access to space than ever before. The Space Shuttle Program promised to both revolutionize and routinize spaceflight.

But, as with all cutting-edge technologies, the risks were severe. A month before STS-1, as Columbia sat on Pad 39A at the Kennedy Space Center in Florida, several technicians were asphyxiated by nitrogen fumes while working in the shuttle’s aft fuselage. Two of them later succumbed to their injuries. The accident served as a deadly reminder that spaceflight is a dangerous business, even when still on Earth.

And Young was well aware of that fact. One afternoon, astronaut Joe Allen bought Young his lunch in the cafeteria. When Young promptly attempted to pay him back, Allen laughed and told Young to forget it. “No,” Young retorted. “You don’t go fly these things when you got debts. All my debts are paid.”

Elegant but risky

Young knew strapping himself atop tons of highly explosive propellants meant to blast him into space was dangerous. But the shuttle — a delta-winged craft awkwardly bolted astride a fuel-filled External Tank and flanked by two Solid Rocket Boosters — was danger on steroids. With no meaningful crew escape mechanism, the shuttle’s ascent profile included several phases (ominously called black zones) in which major emergencies were guaranteed to be fatal.

Ejection seats, parachutes, and pressure suits were available on the shuttle’s first four test flights, but these would be phased out as the system matured. In any case, ejecting directly into toxic rocket exhaust left Young more than a little skeptical of the escape plans. And even if the astronauts did successfully eject, their parachutes might not open in time to save them.

The escape would give them the worst headache, Young mused darkly, albeit a short one.

The first shuttle takes flight

Young and Crippen’s first attempt at launch aboard Columbia on April 10, 1981, was stalled when a timing glitch popped up in one of the shuttle’s computers. Launch was rescheduled for April 12, which happened to mark the 20th anniversary of Yuri Gagarin’s first human spaceflight on Vostok 1.

One minute before launch, the shuttle’s three main engines — which blew up with concerning regularity during ground tests — were ready to go. Columbia’s electronic brain took control of the countdown.

At T-minus 16 seconds, water flooded the launch pad to reduce the energy reflected during liftoff. At T-minus 10 seconds, a flurry of sparklers came alive beneath the main engines to burn off residual hydrogen. At T-minus 6.6 seconds, the engines themselves roared to life, generating copious amounts of steam and yielding a trio of so-called mach diamonds.

With all engines burning at full tilt, the countdown hit zero. The booster ignition produced a dazzling flame, and a harsh staccato crackle shook the 3,500 spectators gathered along the beaches and roadways of Cape Canaveral. Explosive bolts anchoring the behemoth to the pad were severed and at 7 A.M. EDT, allowing seven million pounds of thrust to loft the first shuttle into the sky.

From their seats in Columbia’s cockpit, Young and Crippen felt the vehicle rock back and forth. The incessant vibrations rendered their instruments blurry, but not unreadable. Those vibrations diminished when the boosters were discarded, and Columbia, powered by her engines, sailed smoothly into orbit.

Throughout it all, Young’s heart rate climbed no higher than 90 beats per minute, while Crippen’s peaked at almost 130. Young later joked that his old heart simply refused to beat any quicker. But Flight Director Neil Hutchinson offered another explanation: The cool, unflappable Young must have been asleep the whole time.

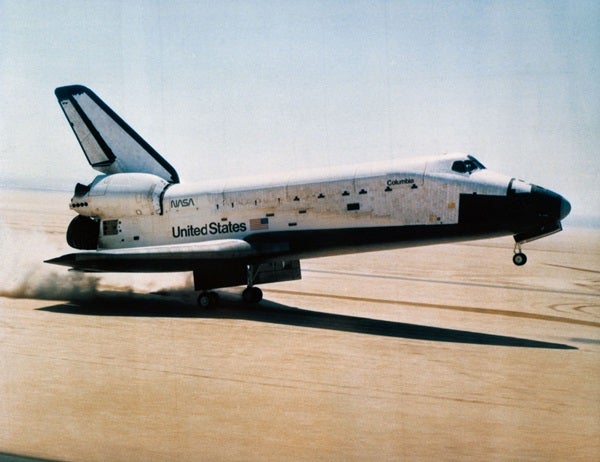

Two days later, Columbia performed a searing hypersonic descent to land on the dry lakebed runway at Edwards Air Force Base in California. It posed an ultimate test for the patchwork of tiles on the spacecraft’s airframe, designed to protect it from the extreme thermal stresses of reentry. During descent, as temperatures doubled, then tripled, then quadrupled, ionized gases around the shuttle morphed from salmon-pink to reddish-orange. The astronauts could only marvel at the hellfires raging a few inches in front of their noses.

As expected, this plasma sheath around the fast-moving shuttle severed radio communications for 20 uncomfortable minutes. Finally, though, the blackout ended, and contact was re-established. “What a way to come to California,” Crippen jubilantly remarked.

But for spectators on the ground, more attuned to the serene approaches of commercial jets, the shuttle’s precipitous descent and phenomenal speed caused hearts to pound. Barreling through the azure sky at an angle some seven times steeper than an airliner — and at almost twice the speed — Young pulled back on the stick, morphing the craft from a falling brick into a flying machine of exquisite grace.

At 10:20 A.M. PDT, Columbia touched down at 212 miles per hour (341 km/h), with her wheels kicking up a rooster-tail of hard-packed sand. As the shuttle came to a halt after a 1.9-mile (3 km) rollout, Young’s characteristic drawl came over the airwaves.

Young asked mission control’s Joe Allen: “Do I have to take it to the hangar, Joe?” Allen chuckled before answering with “We’re gonna dust it off first.”

Not without its flaws

For all its triumphs, STS-1 was not a perfect success. For example, struts that held Columbia to her fuel tank buckled at liftoff, which forced NASA to strengthen them for future flights. Then, of course, thermal protection tiles fell away during a later ascent of Columbia, opening a festering wound which would ultimately doom the shuttle and its crew in January 2003, haunting the program for the rest of its career.

But in April 1981, few foresaw that both Columbia and Challenger would vanish in dreadful tragedies, taking 14 human lives with them. Few imagined that shuttles would go on to visit Russia’s Mir space station. And no one ever dreamed that returning humans to the Moon would use a giant rocket — the Space Launch System (SLS) — whose core stage, engines, and boosters drew their design heritage directly from the shuttle.

And though the Space Shuttle Program never quite fulfilled its promise of extremely rapid and routine access to space, it does remain both symbolic of high technology and iconic for the United States itself.

As John Young triumphantly jabbed the air with both fists and kicked Columbia’s tires forty Aprils ago, his excitement for the future of spaceflight was palpable. “I’ve often claimed that John calmed down” by the time he got outside the shuttle, Crippen said. “But you should’ve seen him when he was inside the cockpit!”