As Eugene Cernan took his last steps on the lunar surface, the Apollo 17 commander promised to come back. “As we leave the Moon at Taurus-Littrow,” Cernan said Dec. 13, 1972, “we leave as we came and, God willing, as we shall return, with peace and hope for all mankind.” It was a callback to a plaque left behind at the base of the Apollo 11 Lunar Module, which stated that the men from planet Earth who had first set foot upon the Moon “came in peace for all mankind.”

But others came peacefully first. Although it left no trace upon the pocked, lonely surface of the Moon, the Apollo 8 mission of December 1968 proved that getting there was possible.

Apollo 8 was crewed by Commander Frank Borman, Command Module Pilot James “Jim” Lovell, and Lunar Module Pilot William “Bill” Anders. The three astronauts were the first to be lofted by Wernher von Braun’s Saturn V rocket. In quick succession, they also became the first to leave Earth’s orbit, to enter the orbit of another celestial body, and to gaze upon the far side of the Moon.

While often overshadowed by the giant leaps of the missions that followed, Apollo 8’s legacy is vast. Perhaps the most well-known artifact from the mission, the famous “Earthrise” photo taken by Anders, is credited with catalyzing the modern environmental movement. Apollo 8’s timing — over Christmas at the close of a tumultuous year — has further imbued the mission with a kind of mythical quality.

Nothing contributed more to this quality than the astronauts’ inspired choice to close their Christmas Eve television broadcast by reading the opening erses from the Book of Genesis. The reading served as a benediction, consecrating the endeavor of space exploration and projecting a sense of optimism and renewal to a global audience. According to a telegram from one grateful viewer, the mission “saved” 1968.

Earlier this year, we visited Lovell, now 95, at his residence outside Chicago. With the mission’s anniversary upon us, we set out to explore the legacy of Apollo 8 with one of the three men who know it best.

Luck of the draw

Fifty-five years later, what Lovell remembers best about Apollo 8 was its timing — one of many lucky draws that would come to define his career. His selection for the mission was a fluke of astronaut scheduling and NASA’s own shifting timelines. First assigned to the backup crew of Apollo 9, Lovell was shifted to its prime crew, and then 9’s crew was swapped for 8. “The timing just came into being,” Lovell says. “It happened that Apollo 8 was ready to go to the Moon, and it happened also that we had to do a flight around the Moon before we could attempt a landing. … We were all interested in seeing if we could make it all the way,” he says.

Apollo 8 went off without a hitch and paved the way for future successes. “Apollo 11 was merely confirming in real time all the stuff that we had done except the actual landing,” Lovell notes. The “actual landing” was a triumph. But Lovell knows that landing isn’t all there is. Indeed, thanks to the near catastrophe of Apollo 13, he is the only person to twice circumnavigate the Moon but never set foot upon it.

As a year of political upheaval, 1968 is remembered primarily for unrest both domestic and international. In 1968, more U.S. soldiers died in Vietnam than in any year before or after; on U.S. soil, the assassinations of Rev. Martin Luther King Jr. and Robert F. Kennedy further destabilized an already fractured homefront.

But in a year plagued by violence, Apollo 8 went to the Moon in peace. Its success was proof, in the words of Anders’ wife, Valerie, “that we could do something besides go to war; we could do something positive with our technology.” For their efforts, the crew were named Time magazine’s Men of the Year. “For all its upheavals and frustrations,” Time proclaimed, “the year would be remembered to the end of time for the dazzling skills and Promethean daring that sent mortals around the moon.”

In hindsight, the idea that a lunar flyby might dull the sting of nearly 17,000 U.S. soldiers dead in Vietnam might be a reach. Claims that Apollo 8 “saved” the year from ruin are subjective. But there is no question that the mission did unite people around the globe. Over the course of the weeklong mission, the crew of Apollo 8 broadcast live a total of six times. These broadcasts were the first to televise from the realm of another planetary body and brought images of the Moon into living rooms worldwide.

The astronauts were told that their broadcasts would have a large audience. But with so little precedent, they had no idea how far their words would reach. “Naturally, I didn’t know how many people [were watching],” Lovell says. For the Christmas Eve broadcast, viewership estimates claim that anywhere from half a billion to a billion people — 1 in every 4 people on Earth — tuned in live. When we told Lovell this, he laughed, rendered speechless by its magnitude more than half a century later: “I can’t talk!” In the lead-up to the mission, what preoccupied the crew most was not the number of viewers, but what to say to whoever did tune in. “This was the first flight to the Moon,” Lovell says. “We were saying to ourselves, ‘What can we do? What can we say back to the people on Earth?’ ”

Advice from Captain Lovell

Artemis 2, the first crewed mission of NASA’s Orion spacecraft, is scheduled to launch in November 2024. It will be the first mission to return to the Moon since Gene Cernan’s promise to do so nearly 50 years prior. Like Apollo 8, it is the first of its program to carry astronauts to the Moon. And, like 8, it will not land. Instead, it will test the equipment, systems, and techniques necessary for the missions that follow.

Apollo 8 was a mission of firsts. But although it will trace its path, Artemis 2 offers a different set of firsts: Its crew will feature the first woman, the first person of color, and the first non-American to embark on a lunar mission. We asked if Lovell had any words of advice for this “new generation of star sailors and dreamers,” as NASA Administrator Bill Nelson has called them. While Lovell — perhaps more than anyone — knows firsthand the dangers of space exploration, he replied only with characteristic humor. “Well, first of all, do they really want to make the trip? Sometimes when you’re finally sitting in the spacecraft and hearing [the] countdown, [you think,] ‘Why did I get into this?’ ”

Begin at the beginning

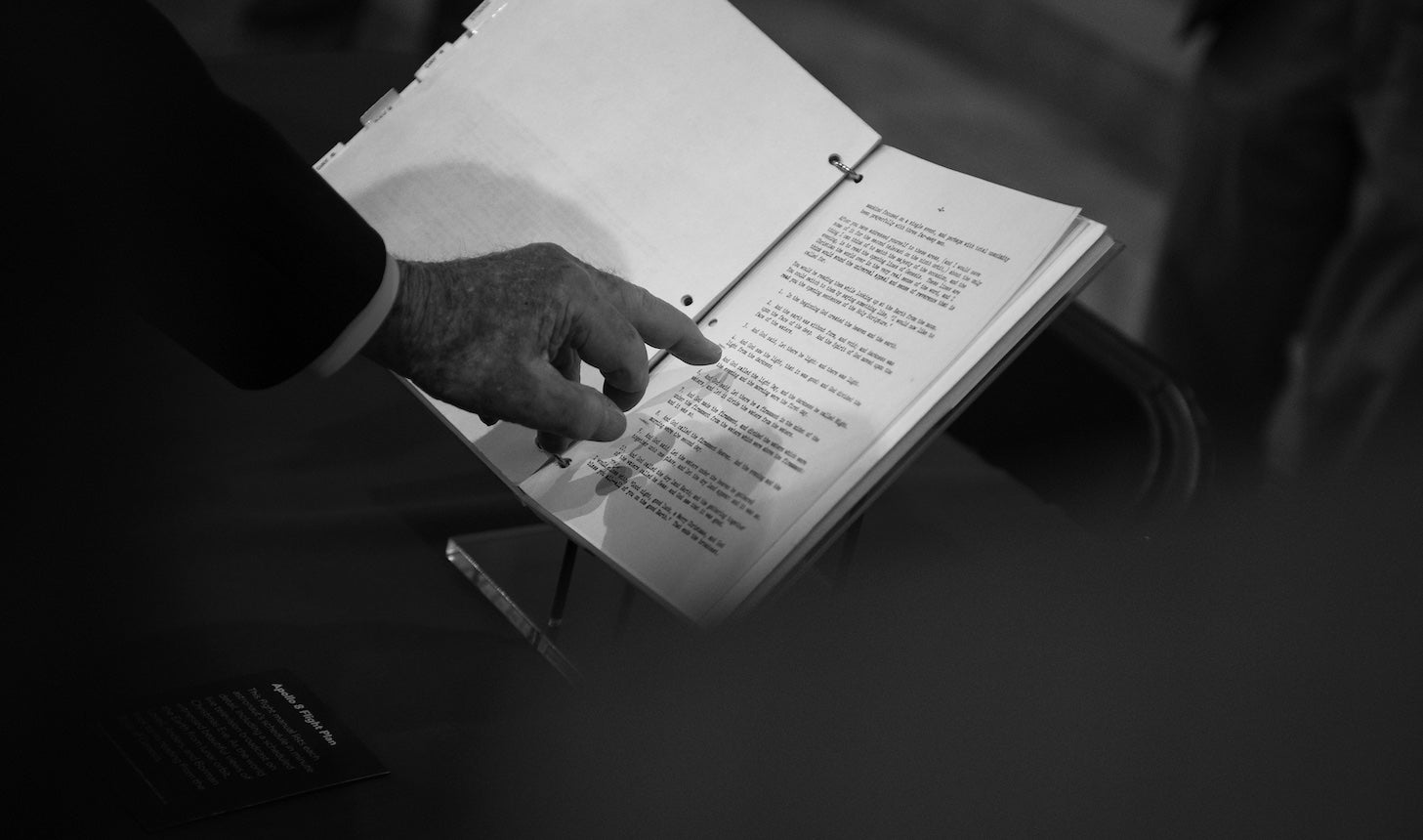

Tasked by NASA Public Affairs Officer Julian Scheer with finding something “appropriate” to say for the historic broadcast, Borman was stumped. He hadn’t even wanted to take the 12-pound (5.4 kilograms) television camera on the flight, a situation in which every ounce was counted. However, while NASA usually gave the mission commander the final say, this was one decision where Borman was overruled. He would later concede that NASA had been right: In the eyes of the public, Apollo 8 would become inextricably linked with the words and images broadcast that Christmas Eve.

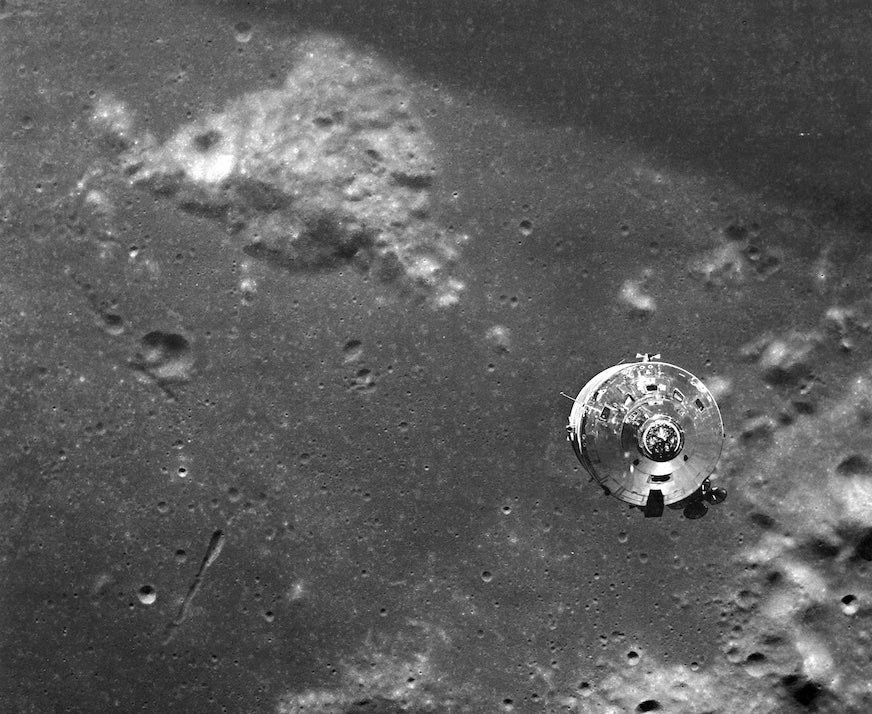

“This is Apollo 8, coming to you live from the Moon,” Borman introduced the staticky broadcast, accompanied by grainy black-and-white footage of the lunar surface. The astronauts then took turns narrating what viewers were seeing, serving as the Moon’s first tour guides. In addition to naming the bumps, craters, and mountains crossing the screen, the men also described their emotional impressions of the alien surface. For Borman, the Moon was a “vast, lonely, forbidding-type existence or expanse of nothing.” For Lovell, it made Earth look like a “grand oasis in the big vastness of space.” Anders commented on the lunar sunrises and sunsets, the “long shadows” and “stark terrain.”

To close, Borman announced that the crew had a final message for the people of Earth. And then each man took turns reading the first 10 verses of the book of Genesis.

The story of how Borman decided on the reading has also become part of the mission’s mythos. Some accounts have suggested that the reading was a spontaneous decision by the astronauts on the flight; others reported that the idea was hatched by Borman’s friend, NASA colleague, and fellow church member Rodney Rose.

The real story is a little more complicated. Borman initially approached his crewmates for their thoughts about what to say; both Anders and Lovell came up blank. He then reached out to his friend Simon Bourgin, who worked for the U.S. Information Agency, and Joe Laitin, a public affairs officer who worked for presidents John F. Kennedy and Lyndon B. Johnson. It was Laitin’s wife Christine — a member of the French resistance during World War II — who came up with the idea to read the first 10 lines of Genesis, which detail the Judeo-Christian account of the creation of Earth. “Why don’t you begin at the beginning?” she suggested.

The astronauts agreed. “We all decided that this was really good,” Lovell told us. “It turned out to be quite appropriate, I think.” After all, Lovell notes, “[it was] Christmas. We thought that the message that it portrayed was at the right time.”

CBS anchor Walter Cronkite agreed. In an interview with PBS, Cronkite later recalled that when the astronauts began the reading, his first impression was that it was “too much” and maybe even a little “corny.” But by the end, the famously taciturn newsman had tears in his eyes. “It was really impressive and just the right thing to do at the moment. Just the right thing,” Cronkite said.

Catalyst for change

There were Americans who disagreed — a few vehemently. The atheist activist Madeline Murray-O’Hair, who came to prominence in 1963 for her successful campaign to remove mandatory prayer and Bible readings from U.S. schools, complained that the reading was “ill advised” and “most unfortunate.” In an interview with a Texas radio station, O’Hair encouraged listeners to write to NASA denouncing the reading as a violation of the separation of church and state. “She didn’t like anything if it had something religious to it,” Lovell says. She later filed a lawsuit on the matter, which was dismissed.

O’Hair’s request resulted in nearly 30,000 letters complaining about the reading. However, it also inspired a massive countercampaign to support the astronauts. Dubbed Project Astronaut, the campaign was organized by national religious organizations and local churches, whose members wrote more than 8 million letters from 1969 to 1975 framing the event as a matter of religious freedom. Many of the letters were sent to NASA and Lovell’s house in Houston. Sometimes, people would even send letters addressed to the Apollo 8 spacecraft itself. “We tried to answer them the best we could,” Lovell says.

Those in support of the Genesis reading ultimately won out. On the Apollo 8 commemorative stamp issued in May 1969, the words “In the beginning God…” — the opening line of Genesis — accompany the famous Earthrise image taken by Anders. This image of Earth, the first of its kind taken by a human from space, is rivalled only by Apollo 17’s “Blue Marble” photograph of the whole Earth as one of the most impactful visuals of the Space Age. While Apollo 8 might not have landed on the Moon, its television broadcasts and photographs brought home both the sight of the lunar landscape and a new perspective on Earth.

Astronauts experience what has come to be called the overview effect, a term coined by space philosopher Frank White to describe the shift in perspective and priorities afforded by viewing Earth from above. In the “big vastness of space,” earthly differences are made to seem small. “The vast loneliness up here of the Moon is awe-inspiring,” says Lovell. “It makes you realize just what you have back there on Earth.”

A gift for eternity

Apollo 8 launched Dec. 21, 1968, and splashed down in the Pacific just under one week later. While the timing may have worked best for NASA — and offered a catchy public framing — it was less than ideal for the families of the astronauts. “Of course, we were all really young,” recounts Susan Lovell, who was 10 years old at the time of the mission. “Our dad was just off doing his job.”

It also posed a dilemma for Lovell: What’s a dad and husband to do when he’s 240,000 miles (386,000 kilometers) away at Christmas? The role was clearly on his mind. Following the trans-Earth injection burn that sent the crew home, his first words back to Houston, in the wee hours of Christmas Day, were: “Please be informed there is a Santa Claus.” And on Christmas morning, he had a mink coat delivered to his wife Marilyn at their southeast Houston home with a card that read, “Merry Christmas and love, from the man in the Moon.”

The mink is still in the Lovell family, but the lasting legacy of Lovell’s 1968 Christmas gifts to Marilyn cannot be held or worn. As the crew flew over the future landing site of Apollo 11, Lovell surveyed the terrain and decided of a particular peak, “Well, I’ll name that Mount Marilyn.” After the crew of Apollo 11 used the name, it stuck. While anyone might buy a coat for their wife, giving her “a mountain, that was something different,” Lovell says.

Marilyn passed away Aug. 27, 2023, at age 93, with Jim at her side. But she remains immortalized on the Moon. Topographical maps of the lunar surface show Mount Marilyn within Montes Secchi, the mountain range separating the seas of Tranquility and Fertility. The name was made official by the International Astronomical Union in 2017.