In a few short weeks, NASA will be just a bit closer to establishing a long-term presence on the Moon — a foundational step toward sending astronauts to Mars. Shooting for a launch date of Aug. 29 (pending optimal weather conditions) the Artemis 1 flight test aims to reach a distant retrograde orbit around the Moon, clocking approximately 1.3 million miles (2.1 million kilometers) over 42 days. Splashdown is expected to occur Oct. 10 off the coast of San Diego.

Artemis 1 is NASA’s first integrated test of their Deep Space Exploration Systems: the Orion spacecraft, the Space Launch System (SLS) rocket, and the upgraded ground systems at Kennedy Space Center in Cape Canaveral, Florida, where the test flight launch will take place. This mission is uncrewed, but it will inform future Artemis missions and help build a foundation for future human expeditions. Orion is specifically designed to support human exploration hundreds of thousands of miles from Earth. And the SLS, the most powerful rocket in history, is built to fly faster and further than any crewed spacecraft has ever flown.

NASA plans for Artemis 2 to be a crewed lunar flyby and for Artemis 3 to focus on a crewed lunar landing mission. Notably, Artemis 3 will be the first time NASA has landed astronauts on the Moon since 1972, and it will be the first time in human history a woman and a person of color will walk on the Moon.

Maiden voyage

Before it can focus on bringing humans back to space, however, NASA needs to stretch its wings. During Artemis 1’s initial flight, NASA’s primary objectives are to test the Orion heat shield when returning through Earth’s atmosphere, evaluate overall operations through the various phases of the mission, and test the process for retrieving the spacecraft after splashdown.

Ultimately NASA wants to confirm “all the things that the Orion program needs to do to look at the capsule to say, ‘Yes, we think we can fly crew on the next one,’” said Melissa Jones, Artemis 1 recovery director, during a press conference at Johnson Space Center on Friday, Aug. 5.

This due diligence isn’t particularly surprising when one considers the extreme conditions Orion will face during its blistering return through Earth’s atmosphere. When it enters the atmosphere, the module will be traveling up to 25,000 mph (40,000 km/h), reaching temperatures around 5,000 degrees Fahrenheit (2,800 degrees Celsius) — faster and hotter than any human-carrying spacecraft that has come before it. So, evaluating the heat shield’s performance is a critical first step before a crewed Artemis mission can take place.

Another key objective as NASA prepares for the future of human space exploration is to understand the risk of high radiation on the human body, as well as basic biological systems. Thus, Artemis 1 will be carrying out biology investigations related to deep-space radiation, including studies examining its impact on the nutritional value of seeds, DNA repair of fungi, adaptation of yeast, and gene expression of algae.

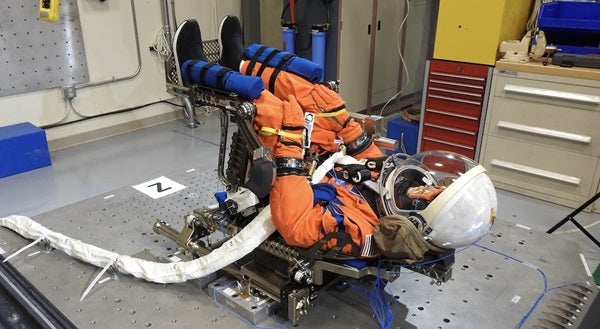

Artemis 1 will also have three manikins onboard the flight to collect safety data and help inform future crewed missions. The “passengers,” named Commander Moonikin Campos, Helga, and Zohar, simulate the human body and will each play a role during this mission.

Commander Moonikin Campos — named via a public contest — will occupy a commander’s seat fitted with sensors to record acceleration and vibration. It will also wear the Orion Crew Survival System spacesuit, specifically designed for launch and re-entry, with two radiation sensors attached.

Helga and Zohar are manikin torsos made up of materials that simulate human bones, soft tissue, and female organs. These models are designed with more than 5,600 passive sensors and 34 active radiation detectors. One of the torsos will wear a radiation protection vest, while the other will act as a control.

Gateway to the solar system

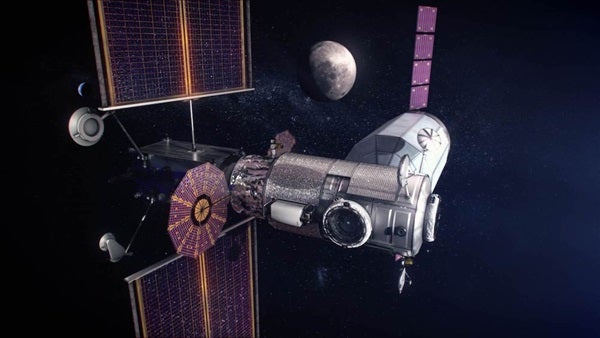

Another vital component of the Artemis missions — and ultimately the cornerstone of NASA’s future for deep-space exploration — is the Gateway program. Based at Johnson Space Center in Houston, the program is building the first space station to orbit the Moon.

Gateway will serve as a multi-purpose outpost, enabling human exploration of the lunar surface and serving as a staging point for expeditions reaching farther into space. Made possible through both international and commercial partnerships, Gateway will have docking ports for different spacecraft, support ongoing scientific research, and include the Habitation and Logistics Outpost (HALO), where crew to live and work onboard.

NASA is designing Gateway to be a pillar upon which all future deep-space exploration is built; a true entryway to making a mission to Mars possible.

“When we think about Artemis, we focus a lot on the Moon, but I just want everybody…to remember, our sights are not set on the Moon — our sights are set clearly on Mars,” said Reid Wiseman, chief astronaut at Johnson Space Center, during the press event. Wiseman emphasized how foundational the Artemis 1 test flight will be for Artemis 2, Artemis 3, and beyond.

“Artemis 3 is leading to the rest of the Artemis program — the first woman, the first person of color on the surface of the Moon, and then the first humans trekking out to Mars and putting our footsteps and building science laboratories and having [access to] another planet,” Wiseman said. “To me, it is just the most awe-inspiring moment that we have had here at NASA.”

The future is indeed already underway, with all sights now set on Aug. 29.