The space agency did not say it had found evidence of alien life. However, these new results are still tantalizing.

Curiosity landed on Mars back in 2012 and it’s been slowly climbing up Mount Sharp, a large hill formed when an asteroid impact created Gale Crater, simultaneously exposing multi-billion year old sedimentary rocks laid down in an ancient lakebed. The rover came equipped with a suite of instruments known as Sample Analysis at Mars, or SAM. And its main goal was to find organic molecules. These commonly form in non-biological processes, but they’re also the building blocks of life.

And mysteriously, the VW Beetle-sized rover succeeded in finding organics even though past Mars missions, like 1976’s Viking landers, did not.

This latest announcement was tied to two scientific papers published simultaneously in the prestigious journal Science. One study focused on the methane and the other looked at the organics.

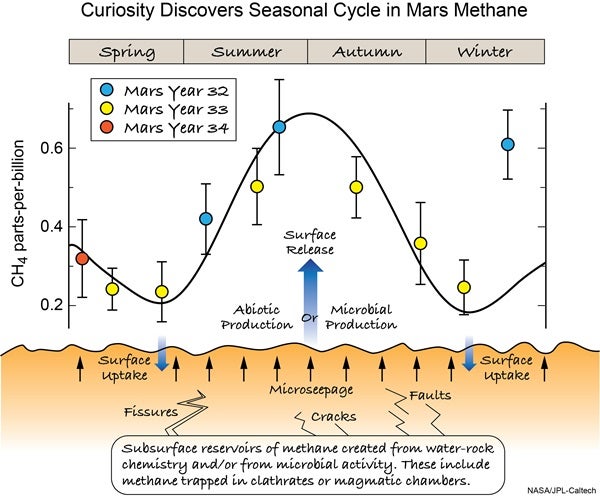

In the first paper, a team analyzed three Mars years worth (55 Earth months) of atmospheric data from Curiosity. In that time, the rover caught methane levels spiking as the seasons changed, growing several times stronger at the height of summer in the northern hemisphere.

Based on the chemical make-up, the scientists suspect this methane was heated up and released from sub-surface reservoirs where it was likely trapped in permafrost. They suspect large amount of the gas may be frozen in such underground reservoirs. But its exact origin remains a mystery.

The other study, led by NASA biogeochemist Jennifer Eigenbrode, examined drill samples of three-billion year old mudstones that Curiosity collected from two different sites in Gale Crater. The rover dropped these samples into an onboard laboratory and cooked them in order to analyze the gasses they threw out.

This is far from the first time Mars researchers have claimed to find methane. Curiosity itself made headlines in recent years after seeing faint methane signals. But scientists have been chasing this gas for decades.

In 1966, a pair of astronomers made a startling announcement during a conference at San Francisco’s Jack Tar Hotel. They’d used a special kind of ground-based telescope to study the atmosphere of Mars, and in the process, they’d deduced the presence of methane. Headlines heralded the significance: Life could exist on Mars.

In the half-century since then, many teams of scientists have published potential signs of methane in Mars’ atmosphere. And each of those sparked hope for finding life, only to fade away without further proof.

“Every chapter in the story of methane on Mars has been a surprise,” says JPL’s Chris Webster, who led the methane study. But each of those signals was sporadic, and “none of them were repeatable.”

This time, they were able to watch the signal come and go. So the find looks destined to stick. What’s far less certain is exactly what it means.

To understand why methane matters so much, you first have to understand what it is.

Methane is a simple molecule — a so-called hydrocarbon — composed of four hydrogen atoms stuck to one carbon atom. It has no natural smell or color. And it’s also common because hydrogen is the most abundant element in the cosmos, and carbon is the third most abundant.

However, it’s also fragile. It can’t handle things too hot. And the oxygen and carbon dioxide in Earth’s atmosphere can break its bonds. So, on Earth, methane doesn’t last long in our atmosphere.

And most of the methane that we do have is produced by biology. Things die and their hydrocarbons get trapped in stores deep underground or in permafrost, where it’s known as a clathrate.

Living things also churn out methane, too. Cows and other livestock produce enormous amounts of the greenhouse gas. And simple lifeforms, known as methanogens, also produce methane.

All this means that, on Earth, methane is a sign of life. That’s given astronomers good reason to see methane as a potential signal of microbes on Mars.

Like Earth, it also has methane-destroying conditions. The Red Planet’s atmosphere is almost completely made of carbon dioxide. And even the ultraviolet light that penetrates Mars’ weak atmosphere could destroy it.

So, any methane we do see must have been released into the atmosphere very recently.

But life isn’t the only process that makes methane. We know that because it’s abundant on Uranus and Neptune. And there’s enough of the stuff to create bizarre landscapes on the surfaces of Pluto and Titan. And even on Earth, a small amount of methane is made in specific sorts of volcanic reactions, even if it doesn’t stick around long.

But Mars has no active volcanoes. And it doesn’t have ways of replenishing methane like those outer solar system worlds.

To truly find out what’s causing these seasonal surges of methane, we’ll need new Mars missions capable of better searching for definitive signs of life. And, thankfully, those spacecraft are already in the works. NASA’s Mars 2020 rover, which will launch in a couple years, is custom-built for this purpose. And the European Space Agency’s ExoMars rover should soon follow with similar aims.

Whatever the final cause — whether microbes or natural chemistry — we’re now closer to finding the source of Mars’ methane than ever before.

This article originally appeared on discovermagazine.com.

Want to learn more about the Red Planet? We’ve got you covered with a couple of free downloadable eBooks with content from Astronomy and Discover magazines: