History’s pages are sprinkled with a litany of ironies, few sourer than a fearsome weapon of war that became a vehicle for peace, evolving from a tool to end human lives in their thousands to one that pushed human life into space.

In the final months of World War II, Nazi Germany’s V-2 (Vergeltungswaffe-2, or “Vengeance Weapon-2”) rained fire, chaos, and terror on the United Kingdom, Belgium, France, and the Netherlands. As the world’s earliest short-range ballistic missile, this 46-foot-tall (14 meters) beast took less than five minutes after launching from mobile batteries in Northern Europe to hit civilian centers, as Adolf Hitler’s tottering regime exacted scathing retribution for Allied bombing of Germany.

Tipped with 2,000 pounds (910 kilograms) of Amatol — a caustic mix of TNT and ammonium nitrate — the V-2 was a formidable wonder weapon. Its liquid-fuelled engine, fed by ethanol/water and liquid oxygen, lifted the V-2 to 55 miles (88 kilometers), attained speeds of 3,580 mph (5,760 km/h)—above Mach 4.8 — and could reach targets 200 miles (320 km) away. Its unsuspecting victims got no warning of its soundless approach and supersonic arrival until the 12.3-ton warhead hit them.

It left craters 30 feet (10 m) across, flattened homes, and from September 1944 to March 1945, killed indiscriminately. As many as 9,000 people died in V-2 attacks – plus 20,000 slave laborers from Nazi concentration camps who worked to death building these missiles in appalling conditions with no sanitation, little sleep, and poor food.

The development of the V-2

Originally called the A-4 (Aggregat-4), the V-2 was the brainchild of Wernher von Braun, the missile maestro and spaceflight visionary whose post-war NASA career spearheaded the birth of the Saturn V Moon rocket. Financed by the German military and championed by artillery commander Walter Dornberger, the A-4 faced a raft of colossal obstacles, from building and cooling a workable liquid-fueled engine to achieving reliable gyroscope control and mastering supersonic aerodynamics.

Von Braun desired the conquest of space. He wanted multistage rockets to reach orbit and scientific sensors to scour Earth’s atmosphere, measuring cosmic rays and micrometeoroids. And Dornberger frequently had to cast cold water on these grandiose fantasies to keep him in check. Von Braun even faced arrest in March 1944 for misusing Nazi funds to advance his dreams of manned spaceflight.

Hitler was initially unimpressed by the A-4, regarding it as an overpriced long-range artillery shell. But as the tide turned against Nazi Germany, his stance shifted to embrace this wonder weapon and seize a strategic advantage — an advantage founded upon terror. Mass production began in 1942 and it received high military priority the next year.

Its development, though, was mired by difficulty, from steam generator maladies to guidance vane failures that resulted in out-of-control tumbles and spectacular explosions. By June 1944, von Braun’s team executed an aggressive campaign of vertical test launches from the Peenemünde research base on Germany’s Baltic Sea.

Just off this wave-lashed coast, launching from the tiny island of Greifswalder Oie, an A-4 designated MW 18014 reached space on June 20, 1944. Today, this steep-sided, mile-long isle is a seabird reserve, hosting migratory flocks of songbirds, ravens and hooded crows. Eight decades ago, it also hosted 28 A-4 launches to investigate heating effects as missiles reentered the atmosphere.

Built in central Germany’s underground Mittelwerk facility then shipped north to Peenemünde, MW 18014’s mission began when its 4,000-rpm turbopump forced fuel and oxidizer into the combustion chamber at 33 gallons (125 liters) per second. The result: a preliminary thrust of 17,900 pounds (8,100 kg), not yet enough to lift the 29,700-pound (14,000 kg) missile off the ground.

MW 18014 launches

But as the turbopump pressurised the fuel, the thrust level rose as blistering exhaust gases of 5,100 degrees Fahrenheit (2,820 degrees Celsius) surged from the engine at 4,500 mph (7,200 km/h). Hammering Greifswalder Oie’s barren terrain with 56,000 pounds (25,000 kg) of fire and fury, the A-4 powered spearlike into the Baltic sky.

As MW 18014 gained altitude, the sky darkened and ambient pressures dropped, increasing the missile’s exhaust impulse to 64,000 pounds (29,000 kg). Guided precisely by four tail-mounted rudders and four internal graphite vanes, it achieved an apogee of 108.5 miles (174.6 km) before falling back to Earth.

By modern standards, MW 18014 reached space. In the U.S., the Federal Aviation Administration (FAA), NASA and the military regard 50 miles (80 km) as space’s lowermost boundary. Much of the rest of the world accepts the 62-mile (100 km) ‘Kármán Line’—named for engineer Theodore von Kármán, who first described it — where ambient air pressures are too weak to support aerodynamic lift.

But neither concept existed in 1944. Over a decade would elapse before the U.S. Air Force started awarding ‘astronaut wings’ to its high-altitude pilots and not until 1960 did the Fédération Aéronautique Internationale (FAI) formally adopt the Kármán Line. As such, MW 18014’s achievement went unnoticed at the time.

Weeks later, the A-4 was renamed the V-2 and in September 1944, its reign of terror began. Mobile batteries launched over 4,300 missiles, visiting death and destruction on multiple targets from London and Antwerp to Paris and Brussels. An attack on a London department store left 168 shoppers dead and a direct hit on an Antwerp cinema killed 567.

It might have arrived on the scene too late to alter the trajectory of WWII, but the V-2’s ability to terrorize was profound.

Early in May 1945, von Braun and other engineers surrendered to advancing U.S. troops, who promptly seized technical documents, tooling, and sufficient parts to build about 80 new missiles. Days later, Soviet forces occupied Peenemünde, capturing hundreds of technicians, laboratories and manufacturing facilities.

In October 1945, Operation Paperclip brought 1,600 German engineers to the U.S. in support of missile research and development. Between 1946 and 1952, multiple V-2s modified with U.S.-built upper stages examined temperatures, pressures and densities in Earth’s upper atmosphere, as well as solar ultraviolet radiation and cosmic rays.

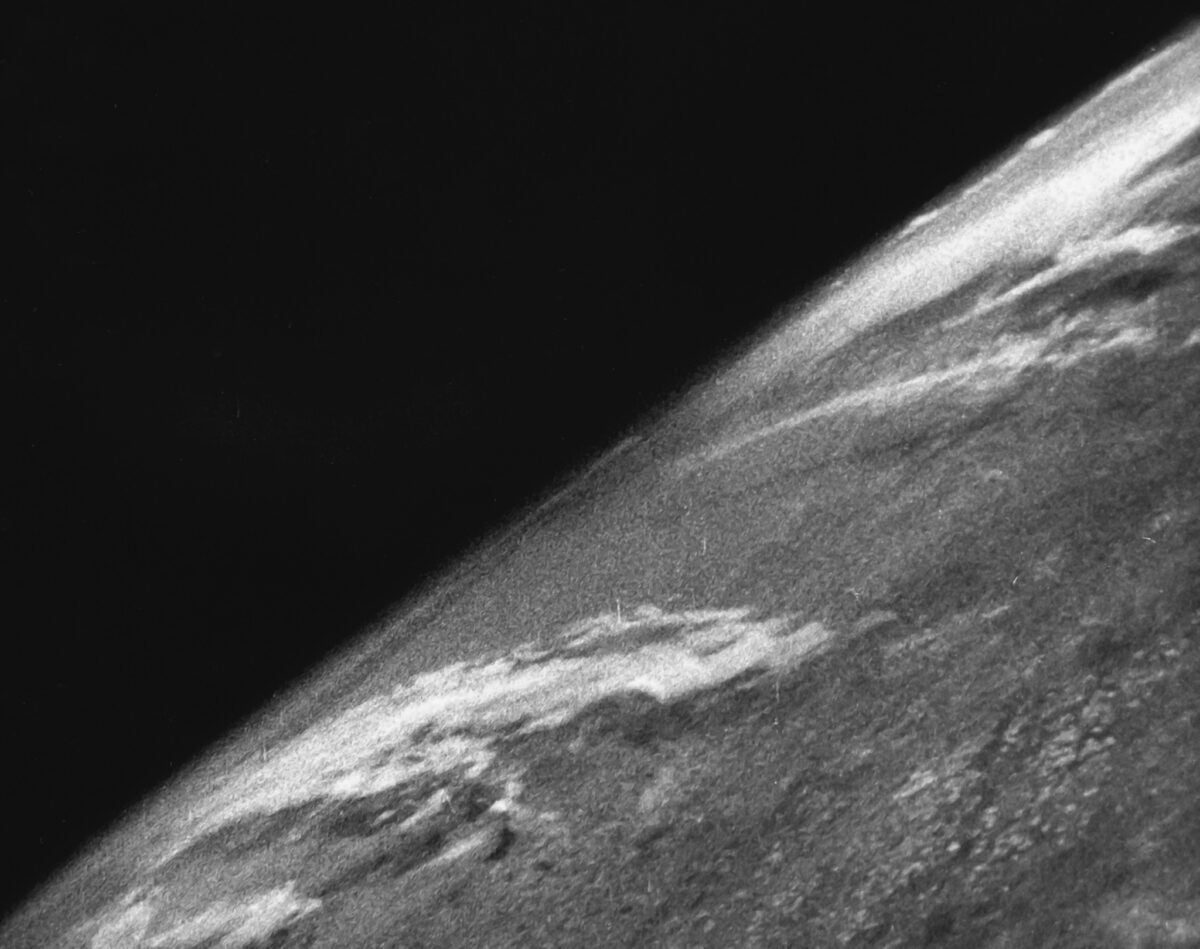

The first image taken from space

One flight in October 1946 photographed Earth from space for the first time, revealing the planet’s curvature and a spectacular vista from San Diego to Salt Lake City and Kansas City to San Antonio. Other V-2s carried fruit flies and seeds, and in June 1948 the rhesus macaque monkey Albert I was the first mammal to ride a rocket. A year later in June 1949, Albert II became the first mammal to reach space, launching to 83 miles (134 km).

The Soviet Union launched multiple captured V-2s and used its specifications to build their first tactical ballistic missile, the R-1. As a sounding rocket, it also launched a pair of dogs, Desik and Tsygan, past the Kármán Line in August 1951. And an early Soviet proposal for a crew capsule lofted by a modified V-2 could have put a man in space by 1948.

Elsewhere, the U.K. flew three captured V-2s as part of Operation Backfire and even proposed an expanded V-2 called Megaroc which might have launched a manned capsule to an altitude of 160 miles (300 km). France’s plans for a “Super V-2” missile proved ultimately too ambitious, but designs found their way into the later Veronique, Diamant, and Ariane rockets.

The legacy of MW 18014

When Alan Shepard became the first American astronaut in May 1961, his Redstone rocket was an outgrowth of the U.S. Army’s PGM-11 Redstone short-range ballistic missile and a direct descendent of the V-2. And one of the key players in the Redstone’s development was von Braun himself, the man who would lead the design of the mighty Saturn V Moon rocket.

Looking back, the V-2 directly enabled multiple national space programs, and the hardware used by today’s rockets owes this poisoned chalice of war a grudging nod of thanks. The flight of MW 18014 also occupies its rightful place in history as the first humanmade object to reach space, a fact lost in the dark days of WWII.

Yet we cannot mislead ourselves, for the V-2 cast a long shadow over humanity’s future. That future was filled with success and sorrow: the triumph of conquering space, set against so many lives pointlessly lost: from 3-year-old Rosemary Clarke, who died in the first V-2 attack on London, to Ivy Millichamp, the missile’s final victim, killed at her kitchen sink. Truly, the V-2 was a devil’s bargain.