The myth that a pioneering astronaut lost his nerve at the end of his first journey to space 60 years ago — which led to the loss of his spacecraft and his near drowning — stains the history of U.S. human spaceflight.

On July 21, 1961, the U.S. launched its second human into space, advancing Project Mercury, America’s response to Soviet space domination. The 15-minute suborbital flight by astronaut Gus Grissom went off without a hitch. Grissom experienced about five minutes of weightlessness, tested an improved autopilot, peered through a large spacecraft window to make navigational observations, and eventually splashed down in the Atlantic Ocean.

The Mercury astronauts had lobbied for a quick-exit exploding hatch for their craft. Grissom’s would be the first flight to test that hatch design. After splashdown, the checklist called for him to deploy recovery aids, which included a whip antenna used to communicate with approaching recovery helicopters. A backup helicopter filmed much of the recovery sequence.

Once a recovery helicopter hooked onto his spacecraft, the plan was for Grissom to arm and detonate the exploding hatch. A sling would be lowered, and he would be hoisted aboard the recovery helicopter as it hauled both man and machine back to a recovery ship.

However, things didn’t go according to plan. The recovery of Grissom’s ship, dubbed Liberty Bell 7, would turn out to be the most perilous part of his flight. As the recovery team approached, the spacecraft’s hatch prematurely blew, forcing Grissom to abandon his flooding capsule. This left him struggling in the ocean for several minutes as his spacesuit took on water. Grissom survived the ordeal. But a myth that he blew the hatch early, causing Liberty Bell 7 to sink into the ocean, started to build.

The loss of Liberty Bell 7 — the worst thing that could happen to an astronaut, short of death — dogged Grissom and his family for the rest of his brief life. Grissom, who went on to command the maiden flight of project Gemini before he perished with his two crewmates in the Apollo 1 fire in 1967, referred to the ordeal as the “hatch crap.”

But if Grissom did not intentionally or even accidentally bump the armed hatch detonator, what caused Liberty Bell 7’s hatch to blow?

NASA managers, anxious to move on to John Glenn’s orbital flight, tried but failed to identify the true cause of the so-called premature hatch actuation. They merely revised recovery procedures to specify the hatch should be armed after the helicopter hooks onto the spacecraft. In doing so, they exonerated themselves from missing a key mission objective: qualifying (human rating) the flightworthiness of the explosive hatch. Given the failure to meet that mission objective, we and others have picked up the thread, examining conditions at the location where the incident occurred — conditions on the day of the flight that NASA investigators were unable to duplicate.

Based on new digital image enhancements and a re-examination of the historical record, it is our contention that the second American to fly in space, U.S. Air Force Col. Virgil Ivan “Gus” Grissom, did not — and was not capable of, by training and temperament — panic at the end of his otherwise successful flight. That narrative has persisted for decades, advanced by the author Tom Wolff in his book and the film, The Right Stuff.

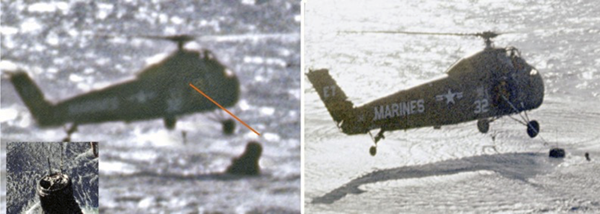

We submit a markedly different interpretation of the flight of Liberty Bell 7 and its conclusion, based on a frame-by-frame re-examination of the highest-quality transfer of the original recovery footage, kindly provided by archivist Stephen Slater. The digital imaging techniques we have applied to this film reveal details previously unavailable. They confirm the recollections of the person closest to Grissom’s spacecraft at the critical moment: U.S. Marine Corps Lieutenant John Reinhard, who was situated at the side door of the prime recovery helicopter. Our enhanced footage has even jogged the memory of another eyewitness, U.S. Marine Corps Lieutenant James Lewis, pilot of the primary helicopter sent to recover Grissom and Liberty Bell 7.

Based on the available evidence, we conclude that electrostatic discharge generated during the ultimately unsuccessful attempt to recover Grissom’s spacecraft most likely caused the premature detonation of the explosive hatch.

Here’s what we believe transpired in the little more than 11 minutes between splashdown and hatch detonation:

After landing in the Atlantic Ocean roughly 300 miles (480 kilometers) east of Cape Canaveral, Florida, Grissom calmly proceeded down his checklist. He undid his harnesses, disconnected his biomedical sensors, and, according to the new recovery procedure, rolled up a neck dam to seal his pressure suit in anticipation of entering the water.

Credit: NASA/Andy Saunders. Source: Stephen Slater

Satisfied that he was in good condition after splashdown, and, according to air-to-ground communications, showing no signs of distress, much less panic, Grissom decided to arm the hatch. First, he removed the hatch restraining wires and a custom survival knife that was attached to the door, placing the latter in his survival pack. He then removed a cover and safety pin to arm the mechanically operated hatch detonator, whose plunger required about 5 pounds (2.3 kilograms) of force to be triggered after the safety pin was removed.

He then prepared for the arrival of recovery helicopters by deploying recovery aids, including a dye marker and a 22-foot-long (6.7 meters) high-frequency whip antenna for communicating with the primary recovery helicopter, Hunt Club 1. Once the hatch sill was hoisted above the water line, the plan was for Grissom to blow the hatch and grab a waiting horse collar.

Hunt Club 1 was piloted by Lewis. Crewman Reinhard was stationed at a side door and prepared to cut the whip antenna according to a new procedure. Cutting the long antenna would allow Lewis to move in unobstructed, so Reinhard could then hook onto the spacecraft after Grissom detonated the hatch.

Reinhard’s tool for the job, referred to as a cookie cutter, was a jury-rigged affair — essentially a tree-pruning pole equipped with cutters actuated by pyrotechnics that were fashioned with the help of engineers at what is now the U.S. Navy’s support facility at Dahlgren, Virginia. (A search of Dahlgren’s archives for details of the device came up empty). The design enabled Reinhard to reach out of the side door of Hunt Club 1 with the long pole and sever the antenna, which could otherwise interfere with the recovery helicopter.

NASA/Andy Saunders. Source: Stephen Slater

Reinhard, who died in July 2020, told researcher Rick Boos in the late 1990s that when he reached down to snip the antenna, he observed an electrostatic arc. “Gus said that he was ready and we slid over,” Reinhard told Boos. “When I touched the antenna, there was an arc.” Reinhard explained that the cookie cutter included two blades with two explosive squibs. At the same time he saw the electrostatic discharge, he recalled, “both [squibs] had gone off without my activating them, and they were on two separate switches!” Pressed by Boos to clarify his observation, Reinhard was unequivocal: “When I touched the antenna there was an arc, and both cutters fired. At the same time, the hatch came off. It could be that some static charge set [the hatch] off.”

While Reinhard did not see the hatch actually blow, he did observe the hatch skipping several feet from the spacecraft, followed seconds later by Grissom, who managed to wedge his way out of the narrow hatch opening. The 5-foot 7-inch (1.7m) astronaut had removed his helmet as water poured into his spacecraft, grabbed the right side of his cockpit display panel, and abandoned ship. He later stated he had “never moved faster.”

Hunt Club 1 was not grounded, as would later become a requirement under U.S Navy and Coast Guard guidelines for sea rescues. Notably, Reinhard was not the only one to experience significant static discharge during such a procedure. Peter Armitage, who helped develop Project Mercury recovery procedures including the cookie cutter, noted in a NASA oral history interview that his un-gloved hands received a jolt during a test run when he touched a boilerplate Mercury spacecraft, much to the amusement of the Marines present. This indicates such discharges were a regular, expected occurrence. Hence, Reinhard’s recollection of static discharge at this moment is not in question.

To corroborate Reinhard’s recollections, we have now enhanced and analyzed the original recovery film footage. The HD transfer was enlarged, enhanced, stabilized, and inspected for any movement near the capsule as Hunt Club 1 approaches, which could indicate the hatch blowing out. The only movement observed in this entire sequence appears in 17 consecutive frames (covering 0.7 seconds) and moves upward and away from the listing spacecraft (these are not film artifacts, as artifacts would only appear on occasional, random frames).

Despite significant enhancement, it is impossible to positively determine that this is the hatch. It does appear to contain a small, solid dark area among a more widespread dark region. This is indicative of the hatch blowing out among spray from the ocean, as the threshold of the hatch would have been below the water line because Liberty Bell 7 was listing at this point in the footage. This corroborates Grissom’s later statement: “I heard the hatch blow … looked up to see blue sky … and water start to spill over the doorsill.” It is also telling that this movement, which cannot be a film artifact, starts at the precise location of the hatch, as confirmed by superimposing a later frame showing Grissom’s egress, and moves in an upward and outward direction.

The location of the hatch can be determined as Grissom exits the capsule in these later, stacked and enhanced frames. The snipped antenna is clearly visible.

If this is the hatch, then what is happening with Hunt Club 1 at this precise moment? Single frames reveal little, particularly because the events were shot on small-format film from great distance and into the Sun. The enhanced film, however, reveals the shadows in the silhouetted side of Hunt Club 1. We achieved this by stacking the 17 frames that include the unusual movement, along with an additional few frames on either side to cover approximately 1 second of elapsed time. This stacking process significantly enhances detail and remarkably, for the first time, reveals Reinhard standing in the doorway of the recovery helicopter with a pole outstretched toward the capsule.

A straight line following the direction of the visible section of the pole was superimposed beyond where it becomes less visible. The line intersects the exact location above the capsule where the antenna was cut:

Along with the cookie cutter mentioned above, Reinhard’s other tool was a pole commonly referred to as a “shepherd’s hook,” which would be used to snag the recovery ring on Liberty Bell 7. Scaling a later frame that shows the length of the separate shepherd’s hook pole confirms that, if both poles are of similar length, Reinhard could certainly have reached the antenna at this moment.

Our conclusion from the new image enhancement and analysis is that Reinhard was almost certainly cutting the antenna at the precise moment that upward and outward movement is observed from the location of the hatch in 17 consecutive enhanced frames. Grissom is seen exiting the spacecraft 5.2 seconds later.

We believe the recovery operations generated a static shock as the cutter contacted the antenna. The timeline of events, observed in the newly enhanced images, also appears to confirm Reinhard’s version of events.

The electrostatic discharge was sufficient to inadvertently activate the pyrotechnic devices on the cutter. But could it also have activated the explosive hatch?

The hatch was secured to the doorsill by seventy (70) ¼-inch-diameter (3.6 cm) titanium bolts with 0.06-inch (0.2 cm) holes drilled into each bolt to provide a weak point. A mild detonating fuse was installed in the channel between the inner and outer hatch seals. When ignited, the explosion caused the weakened bolts to fail, blowing the hatch.

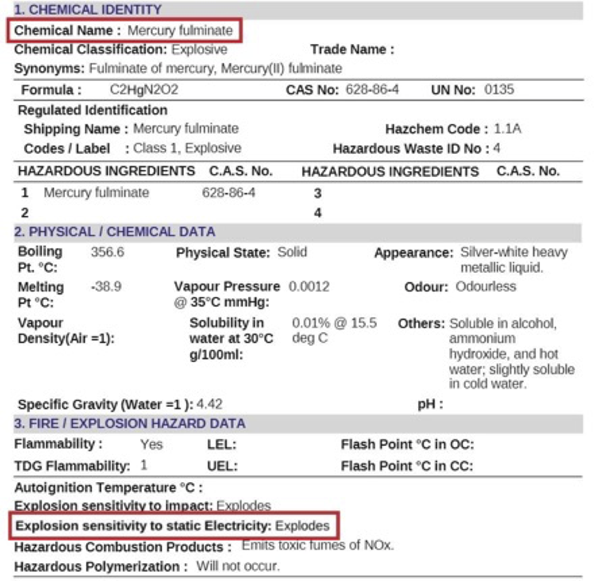

According to salvage expert Curt Newport, who recovered Liberty Bell 7 in 1999, the detonator percussion caps that served as a triggering mechanism likely contained mercury fulminate. Industry specifications provided to us by Newport warn that the inherently unstable compound “can detonate” in the presence of static electricity. Further, a NASA manual on the design and qualification of spacecraft pyrotechnics makes several references to static electricity as a safety concern. The manual also urges designers to “prevent inadvertent initiation” of spacecraft pyrotechnics by “electrostatic discharge.”

Other Mercury spacecraft components were subject to rigorous reliability testing in efforts to achieve “five nines,” or 99.999 percent reliability. Robert Voas, who assisted with early astronaut training, told us the exploding hatch was a “Johnny-come-lately thing that had never been tested by another flight.” Voas continued: “My view of this incident is that it was produced by the relatively last minute change in going to an explosive door … you have to, of course, engineer the door. You have to consider every item on that spacecraft was subject to the reliability program.”

Grissom made one mistake: arming the hatch before the hatch sill was safely above the water line. This likely reflected his unfamiliarity with the hatch mechanism and inadequate recovery training. The one and perhaps only known field test of the exploding hatch occurred on July 10, 1961, with astronaut Grissom observing. The test was conducted little more than a week before Grissom’s scheduled launch date, further indicating what Voas concluded was a rushed development and testing program for the new hatch, as well as inadequate training in recovery procedures.

It is telling that the Liberty Bell 7 recovery procedures were never again used. Recovery steps for later Mercury flights explicitly stipulated that the detonator should not be armed until a recovery helicopter hooked on and lifted the hatch sill above the water line.

Fellow astronauts took to heart the hard lesson of Grissom’s near drowning, as he struggled to stay afloat amid Hunt Club 1’s considerable prop wash. (Grissom had rolled up his neck dam to keep seawater from seeping into his pressure suit, but forgot — or never had a chance — to close an oxygen inlet on his suit, which caused him to quickly lose buoyancy in the ocean swells.)

On all later Mercury flights except one, the astronauts choose to blow the hatch while on the deck of the recovery ship. Wally Schirra sustained a cut to his gloved hand from the plunger recoil, an injury Grissom did not have. Through the years, Schirra repeatedly pointed to this fact as proof that Grissom did not touch, deliberately or accidentally, the hatch detonator (or, as space veterans called it, the “chicken switch”).

The suggestion that Grissom panicked at the end of his flight is patently absurd. Why, after flying a ballistic trajectory atop a Redstone rocket, experiencing weightlessness for five minutes, pulling as many as 10 Gs during re-entry, observing a triangular rip in his main recovery parachute — why would Grissom panic? If anything, bobbing in the warm Atlantic, 60 years ago this week, the astronaut surely would have been relieved to have survived his flight. Grissom can be seen in the recovery footage swimming toward his spacecraft, guiding the recovery team to hook the recovery line, even giving the double thumbs up while treading water.

We showed our results to Hunt Club 1 pilot Jim Lewis, who since the day of Grissom’s flight had recalled a different scenario. His reaction?

“My original impression of events was that the hatch blew as I was completing our approach to Liberty Bell 7, but Andy Saunders’s awesome work on the recovery film has really made me re-examine my memory banks,” Lewis said in an email exchange. “Based on this work, Reinhard must have cut the antenna a mere second or two before I got us in a position for him to attach our harness to the capsule lifting bale. It would appear that the hatch may well have blown at this moment, something that this extensive background research appears to corroborate.”

It is said that static electricity follows the path of least resistance. If so, we posit that an electron filled vortex generated by helicopter prop wash likely generated an arc that detonated the unqualified exploding hatch that was hastily tested and installed on Liberty Bell 7.

As the recovery footage becomes clearer, so too have the waters, which were muddied for six decades by hearsay and speculation over one of NASA’s most enduring mysteries. Gus Grissom, in the scenario we present here on the 60th anniversary of his flight, can at last be fully exonerated from blame for prematurely blowing the hatch of Liberty Bell 7.

The authors wish to acknowledge the tireless research from Rick Boos (who died this year due to complications from COVID-19).

George Leopold (Twitter: @gleopold1) is the author of Calculated Risk: The Supersonic Life and Times of Gus Grissom.

Andy Saunders (Twitter: @AndySaunders_1 and Instagram: andysaunders_1) is an imaging specialist and author of the upcoming book Apollo Remastered, now available for pre-order, here. You can sign up for further updates on the book at ApolloRemastered.com.