The space shuttle era was a time of many firsts for space exploration. Most prominently, it marked the regular usage of the first reusable spacecraft to carry humans into low Earth orbit. In its 30-year history since beginning in 1981, the Space Shuttle Program’s fleet — Columbia, Challenger, Discovery, Atlantis, and Endeavour — flew 135 missions, clocking in at a total of 1,334 days, 1 hour, 36 minutes, and 44 seconds in space. In that time, astronauts helped build and maintain the International Space Station and deployed laboratories and satellites to space. The shuttle program came to an end when Atlantis touched down at the Kennedy Space Center on July 21, 2011.

Since then, the three remaining space-flown shuttles, Discovery, Endeavour, and Atlantis, have been put on public display in museums across the United States. Each one is curated to showcase its history and as a reminder of each shuttle’s scientific contributions.

Earlier this year, Atlantis celebrated its 10th anniversary since it was welcomed to its permanent home at the Kennedy Space Center Visitor Complex in Florida. And Endeavour is getting an update to its permanent museum home at the California Science Center.

As retired space relics, the orbiters inspire, teach, and astound visitors who venture into their exhibits. Thousands of hours have been spent to ensure that their exhibits tell each orbiter’s story and preserving it for generations. With the shuttles now a decade into retired life, Astronomy spoke to the curators of Endeavour and Atlantis to learn more these historic crafts’ new missions.

Space Shuttle Endeavour (OV-105)

When Endeavour launched on its final mission in May 2011, it brought spare parts to the International Space Station and delivered a the $2-billion astrophysics experiment: the Alpha Magnetic Spectrometer. After Endeavour touched down for the last time June 1, 2011, NASA began preparing to the shuttle for its forever home at the California Science Center in Los Angeles.

Endeavour was delivered to L.A. atop one of NASA’s Shuttle Carrier Aircraft, a modified Boeing 747. At the Los Angeles International Airport, crowds welcomed the orbiter’s return to its birthplace in California (like every other shuttle, it was constructed in Palmdale by Rockwell International). After landing, the orbiter was removed from the 747 with a crane, placed on a transporter, and began its 12-mile (19 kilometers) trek to the California Science Center.

The streets of Los Angeles were swarming with excitement as onlookers stretched their necks and pulled out their cameras and phones to take photos of the Endeavour orbiter. “Oh my goodness, the entire city was like the largest block party that the city of Los Angeles had ever had,” says Kenneth Phillips, the aerospace science curator at the California Science Center.

On its journey from LAX, Endeavour weaved through neighborhoods with outstretched wings, carefully maneuvering around sidewalk trees and crowds of enthused onlookers at a leisurely 2 mph (3.2 km/h). “Fortunately, we have boulevards that are wide enough to accept the wingspan because you can’t take the orbiter apart,” says Phillips. Processions of cars followed before and behind Endeavour. Astronauts who flew on Endeavour paraded alongside the orbiter and interacted with the crowds.

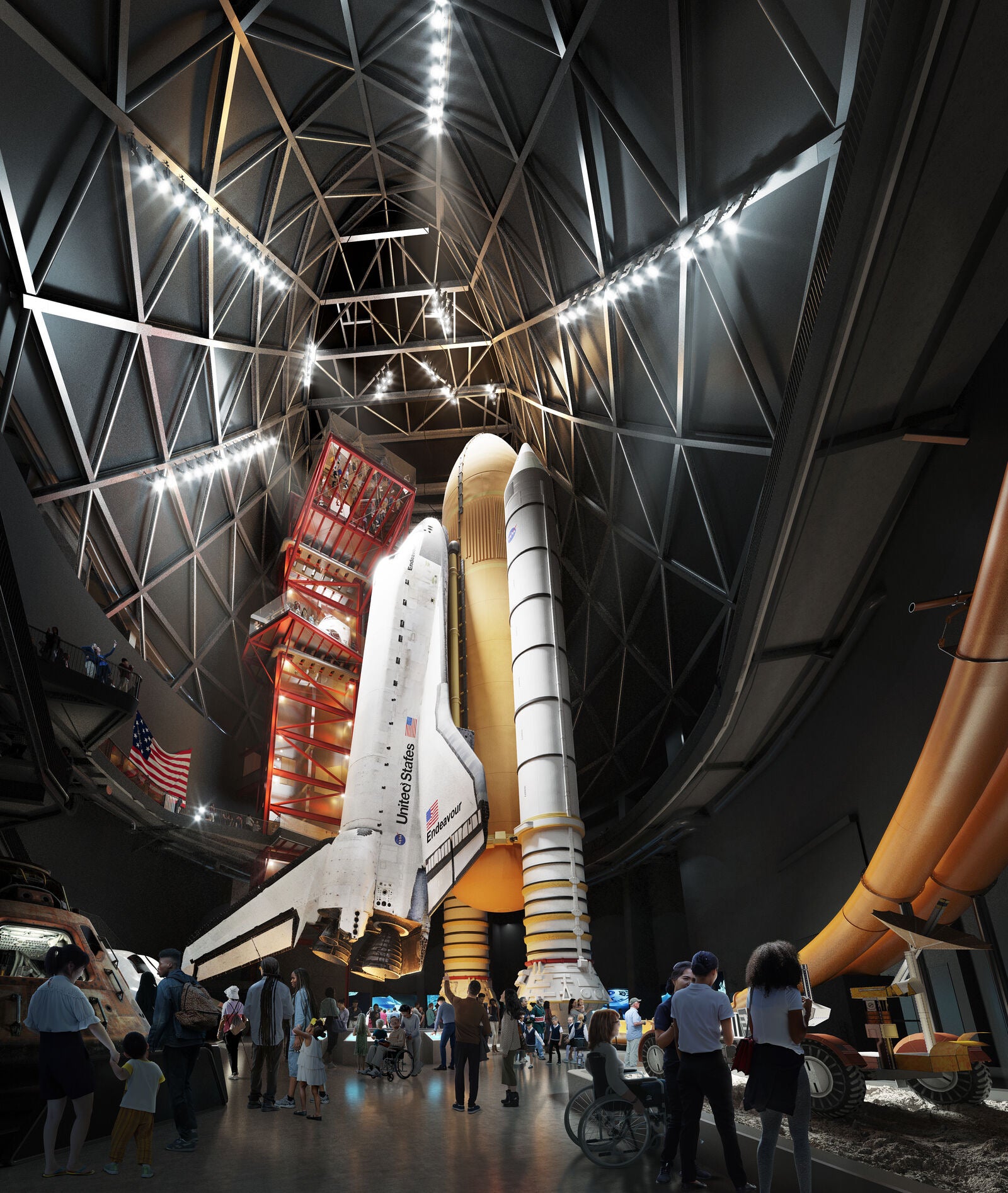

For nearly 12 years, Endeavour has dazzled visitors on display in a temporary hangar at the Samuel Oschin Pavilion at the California Science Center in the same horizontal position when it rolled in. But the museum is now preparing to move the orbiter into its new home, where Endeavour will be reunited with its rocket stack and shifted into a “ready to launch” position. The stack includes NASA’s last remaining external fuel tank built for flight and two rocket boosters recovered from previous launches, making it the first vertical display of a shuttle.

Phillips says that since Endeavour arrived at the museum in 2012, the plan was always to display the orbiter in an awe-inspiring way and showcase the level of effort required to launch the 160,000-pound (73,000 kilograms) shuttle into space. “It takes the large orange external tank and the two solid rocket boosters strapped to the side of the tank to lift the entire stack,” says Phillips. The new building, dubbed the Samuel Oschin Air and Space Center, will have to be built around the Endeavour orbiter and its accompanying shuttle stack. Once complete, visitors will ascend the gantry tower adjacent to the rockets, just like an astronaut preparing for flight.

Endeavour, built to replace the shuttle Challenger, cost about $1.7 billion and was the last space shuttle ever built. For many scientists, including Phillips, Endeavour represented hope following the Challenger disaster.

“I have a dear friend, a good friend, who was on the Space Shuttle Challenger when we lost it in 1986… So, it kind of makes me think that my buddy, my friend [Dr. Ronald McNair], was beaming when I had the spaceship that replaced the one he was on, which is great,” says Phillips. “It’s nice to have that particular ship.”

Endeavour also was reconfigured in 2014 when, still in its horizontal position, its cargo bay was loaded with the SpaceHAB module, to look as it did during the 2007 STS-118 mission. “SpaceHAB is a pressurized module that connects to the part where the astronauts flew in the front of the shuttle, so you could do laboratory experiments and things like that,” says Phillips.

On that mission, Barbara Morgan, NASA’s first educator astronaut and original backup astronaut to Challenger’s Christa McAuliffe, flew 5.3 million miles (8.5 million km) in space during the two-week mission to help construct the International Space Station. “We replicated that as closely as possible as a nod to teachers and educators. So, we have what I call ‘The Teacher’s Shuttle,’ which is great,” Phillips says. The California Science Center recently added a replica Orbiter Boom Sensor System (OBSS) — a boom extension to the shuttle’s Canadian-built robotic arm — to the payload bay, adding to the authenticity of what the shuttle looked like during STS-118.

Three weeks after it was installed with tools from NASA and the Smithsonian, the payload doors were closed again. Once the shuttle is attached to its launch stack in the new building, one of the cargo bay doors will be reopened to show off the SpaceHAB payload.

Among other firsts, Endeavour flew Mae Jemison, the first African American woman in space, in 1992 on STS-47. It was the first orbiter to service the Hubble Space Telescope, installing equipment in 1993 on STS-61 to correct the observatory’s flawed mirrors. It delivered to orbit the first American contribution to the International Space Station, a module named Unity, and also carried out the final ISS assembly mission. “It was sort of the bookends, the alpha and the omega of the assembly of the International Space Station,” Phillips says.

Space Shuttle Atlantis (OV-104)

Like Endeavour, the Atlantis orbiter made a trek over ground to its final home — in this case, a 10 mile (16 km) ride on a transporter from the Vehicle Assembly Building at NASA’s Kennedy Space Center in Florida to the Kennedy Space Center Visitor Complex, where it was welcomed with dozens of sparkling fireworks. Soon after it arrived, Atlantis was shrink-wrapped in 16,000 square feet of protective plastic like a boat to protect it from the construction as its new building was developed around it.

The Atlantis orbiter is the only shuttle displayed in an in-flight configuration with its payload doors open. Curators wanted to display Atlantis in this position because it allowed visitors to see it as astronauts would have. “We’ve seen people be floored by their first encounter with Atlantis, coming nose to nose with this vehicle and having an unexpected and powerful reaction,” says Jennifer Mayo, senior manager of project development at the Kennedy Space Center Visitor Complex. “It’s like the shuttle has a personality of its own that touches people.”

The shuttle greets visitors head-on with an outstretched second-generation Canadarm and tilts as if it’s orbiting in space. Currently, there are no plans to remodel the Atlantis exhibit. “The attraction is so well done and has such a lasting impact on guests even a decade after it was put in place,” says Mayo. “Much magic is left in this display for years to come.”

Orbiter preservation

Before any orbiter was placed on display, NASA had to “safe the orbiter” for the public —removing fuels from the orbital maneuvering engines, taking out some interior components that were toxic, and preparing each orbiter for their flight on a Boeing 747. The engines were removed and replaced with replicas. Each orbiter’s avionics, lockers, tools, and toilets were removed.

Each shuttle on display was preserved to showcase the miles each shuttle endured and the beating they took as they reentered Earth’s atmosphere at blazing speeds. For the orbiters on display, the goal is to keep them looking as they did on their last flight home. “If you look closely at the tiles and know where to look, you’ll see some of them are damaged,” Phillips says of Endeavour. “That happens almost all the time when a shuttle launches. Normally they would be repaired for re-flight, but we didn’t want to fix we wanted it exactly as it was for its last mission.”

And to keep them looking spiffy, there is always maintenance. “Areas more prone to dust collection are cleaned weekly. There are also quarterly preventive maintenance tasks to address hard-to-reach areas,” Mayo says of Atlantis’ upkeep routine.

Completing Endeavour’s new exhibit is expected to take several years. While the new building is built around it, Endeavour will be surrounded by a protective scaffolding of plywood and Kevlar fabric. The orbiter is currently on display in its stacked configuration until December 31, 2023, when construction on the Samuel Oschin Air and Space Center will commence. The shuttle will return to the public eye after the Samuel Oschin Air and Space Center is completed. “It’s going to be quite the experience,” says Phillips.