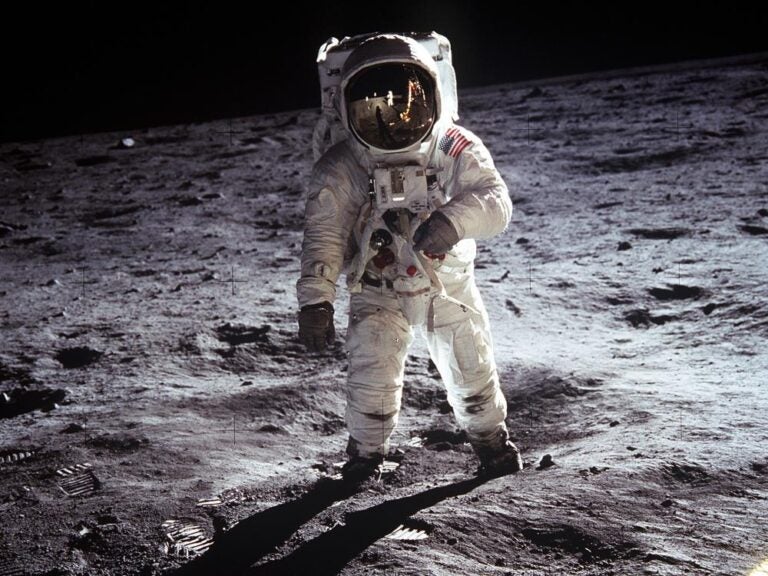

Astronauts have been cataloging the presence of microbes in space for a while now. They need to make sure their home in space is safe, and not growing colonies of harmful microbial critters. But in many other ways, the health and fertility of such microbes can teach researchers a lot about how living things — up to humans — respond to the harsh environment of outer space.

Recently, Marta Cortesão, a microbiologist at the German Aerospace Center, found that two types of mold in particular can survive radiation doses that would kill a human 200 times over. She reported her findings June 28 at the Astrobiology Science Conference in Seattle.

Hardy Fungus

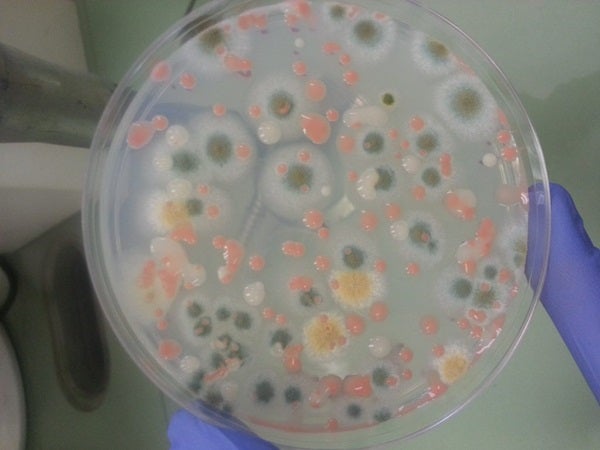

Two of the most common molds found on the International Space Station (ISS) are Aspergillus and Penicillium. They’re usually not harmful, unless inhaled in large quantities by someone who already has a weakened immune system, unlikely with fit astronaut crews. So their presence on the ISS isn’t a problem in itself. But their extreme radiation tolerance raises other questions.

Cortesão tested samples of the two fungi on Earth with ionizing radiation from X-rays, heavy ions and high-energy ultraviolet light. These are all types of radiation that rarely or never make it to Earth or even the ISS, thanks to the protection of Earth’s magnetic field. But they will be present on longer trips to the Moon or Mars, both trips NASA is planning in the near future.

A trip to Mars, for instance, will deliver a cumulative radiation dose of about 0.7 gray. If delivered all at once, 0.5 gray is enough to cause radiation sickness. Five gray will kill a human outright.

The fungi Cortesão tested survived being blasted with 1,000 gray of X-ray radiation, 500 gray of heavy ions, and large doses of UV radiation.

Fungus Beyond Us

While Aspergillus and Pennicillium aren’t an immediate threat to human space travelers, one of the key questions on Mars is whether life was or even is now possible. Similar questions are being asked about Saturn’s moon Titan, which just received its own dedicated mission.

NASA has serious guidelines in place for sterilizing any spacecraft that visits other solar system destinations, both on the outgoing trip to prevent contaminating our own search for life, and on the return trip to keep Earth safe from alien microbes.

But findings like Cortesão’s make that a harder problem to tackle. Researchers have discovered microbes that can endure vacuum, heat and hard radiation, all common methods of sterilization.

Contamination issues aside, her findings also lend weight to theories of panspermia. This is the idea that life might not have developed first on Earth, but was instead delivered by asteroids, comets, or other space-faring objects. While Cortesão tested only her fungus’ radiation tolerance, it’s a step toward showing that microbial life can travel successfully through space, and survive on worlds that seem otherwise too harsh for life as we commonly think about it.

On the other hand, Cortesão’s fungi prove that NASA and other space agencies need to be extra careful not to trust that the harsh environment of space travel alone will give them a clean slate when looking for life on alien worlds. It seems more possible than ever that the first microbes humans find on Mars might be the same ones they brought on a free ride from Earth.