Strange as it may sound, where the astronauts sat (or “sat” – the crew actually stood) in the Apollo Lunar Module may have profoundly impacted the way the experience of walking on the Moon affected them.

Mission commanders were in what is referred to in aviation as the “left seat” position and lunar module pilots were in the “right seat,” where the co-pilot traditionally sits. The commanders returned from the missions seemingly largely unchanged. All but one of the lunar module pilots, in contrast, underwent deep and lasting personal transformations (some of which were profoundly unpleasant) after their Moon missions.

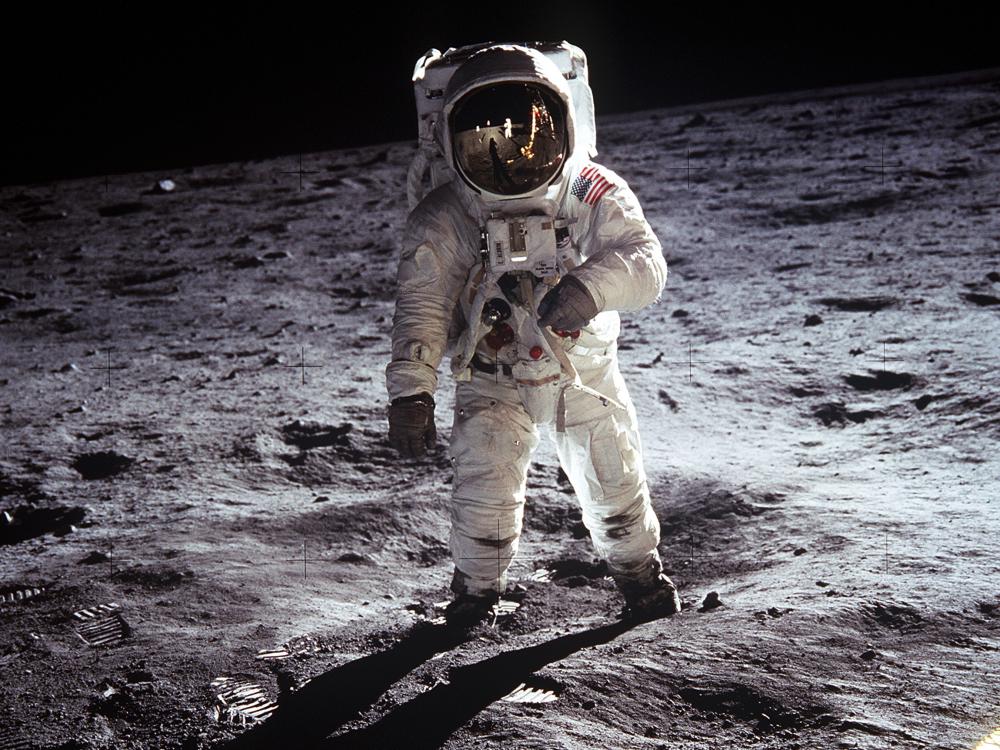

Apollo 11

Apollo 11 saw Commander Neil Armstrong in the left seat, and Lunar Module Pilot Buzz Aldrin in the right seat. After piloting the lunar module Eagle down to the first-ever Moon landing, Armstrong emerged to become the first human to ever set foot upon the Moon. A short while later, Aldrin joined him on the surface in the Sea of Tranquility. Upon returning to Earth, Armstrong, Aldrin, and Command Module Pilot Michael Collins took part in ticker tape parades, addressed a joint session of the U.S. Congress, and completed (some might say endured) a round-the-world tour of 22 countries in 38 days.

Armstrong, always a quiet and reticent individual, soon retired from flight status and took an administrative post with NASA in Washington, D.C. After a year, he left to become a professor of engineering before eventually moving on to pursue business and speaking opportunities. According to historian James Hansen’s book First Man, Armstrong always kept a low profile, rarely gave interviews or autographs, and (other than serving on several high-profile NASA commissions) largely stayed out of the limelight until his death in 2012 at the age of 82.

Aldrin, however, had quite a different post-flight experience. As detailed in historian Andrew Chaikin’s book, A Man on the Moon, and astronaut John Young’s autobiography Forever Young, Aldrin lobbied hard within NASA to be the first person to walk on the Moon but had been bluntly overruled by NASA. Aldrin coped with his disappointment, the stress of the world tour, and his subsequent notoriety through drinking and descended into alcoholism, depression, infidelity, and divorce from his first wife, Joan. Aldrin wrote about these struggles in two autobiographical books, Return to Earth and Magnificent Desolation, stating, “At first the alcohol soothed the depression, making it at least somewhat bearable. But the situation progressed into depressive-alcoholic binges in which I would withdraw like a hermit into my apartment.” Other marriages and divorces followed. Aldrin made a slow climb back to sobriety and mental health. Aldrin is alive and continues to make public appearances today, aged 94.

Apollo 12

Apollo 12, commanded by Pete Conrad with Alan Bean as lunar module pilot, touched down in the Ocean of Storms in November of 1969. Conrad, a notorious prankster, retained his light-hearted personality and often insisted that going to the Moon didn’t change him. In fact, Conrad told Chaikin that when he was selected as an astronaut in 1962 that he promised his wife Jane that it would not change him, and he was true to his word. Conrad went on to command the first crewed Skylab mission. Bean, on the other hand, told Chaikin that he decided before he even returned to Earth to radically change his life and pursue his passions, most notably painting. After commanding the second crewed Skylab mission and working in NASA administration, Bean left to become a full-time artist. Bean told Chaikin that when he was asked by his puzzled colleagues if he could make a living by painting, his response was, “If I can go to the moon, I can learn to be a good artist.”

Apollo 14

After Apollo 13’s near-disaster and aborted Moon landing, Apollo 14 (1971) saw America’s first astronaut, Alan Shepard, as the commander with Ed Mitchell as lunar module pilot. Shepard, famously stern and severe, returned home from his visit to the Fra Mauro lunar highlands to move right back into his old post as chief of the Astronaut Office at NASA. Joking about how little the trip had changed him, Shepard said, “Before I went to the moon, I was a rotten S.O.B. Now I’m just an S.O.B.” Mitchell, already interested in the paranormal, famously conducted secret psychic experiments during the Apollo 14 mission. Mitchell stated, “I had a knee pad with columns on it where I could randomize the numbers and symbols, so-called Zinner symbols, and order them randomly and think about it for 15 seconds. I then took them back [to Earth] and let the people on the ground that were receiving it at stated times send me their answers.” During the mission, Mitchell had a powerful spiritual experience and stated, “The presence of divinity became almost palpable, and I knew that life in the universe was not just an accident based on random processes . . . The knowledge came to me directly.” After the Moon mission, he left NASA to pursue his interest in paranormal topics. He founded the Institute of Noetic Sciences to study parapsychology, experimented with psychedelic drugs, publicly stated that UFOs with extraterrestrials were regularly visiting Earth, and wrote extensively on psychic phenomenon. Many of the astronauts distanced themselves from Mitchell for these activities, but he remained steadfast in his beliefs until his death in 2016.

Apollo 15

Apollo 15 (1971), commanded by Dave Scott with Jim Irwin as his lunar module pilot, found the crew caught up in a scandal upon their return to Earth. The pair, along with Command Module Pilot Al Worden, were accused of conspiring to sell postal covers they had brought to the Moon. The resulting inquiry seriously damaged the reputations of all three men. Still, Scott went on to have a successful career as a NASA administrator and businessman, later turning to consulting. Irwin, who experienced a serious cardiac arrhythmia on the Moon, also underwent a profound religious experience during the mission. Irwin stated that he was a “silent Christian” before his Moon mission, but told author Harry Hurt (For All Mankind) that he “felt the presence of the Lord on the Moon.” Irwin became a deeply observant Christian after the mission. He founded an Evangelical Christian organization, High Flight, wrote a book about Christ-centered living, and later made multiple expeditions to Mount Ararat in Turkey looking for pieces of Noah’s Ark.

Apollo 16

Apollo 16 (1972) was commanded by John Young with Lunar Module Pilot Charlie Duke. Called “the astronaut’s astronaut” by Emerita Curator Valerie Neal of the National Air and Space Museum’s Department of Space History, Young returned from the mission to be head of the Astronaut Office, became the first person to command a space shuttle mission, and remained an active astronaut until he finished his second shuttle flight in 1983. Duke felt a marked sense of emptiness after the Moon mission and began looking to fill the void. Leaving NASA, he found wealth in the business world but it did nothing for him emotionally. Duke found religion and committed his life to Jesus, which he felt saved his marriage and his relationships with his children. Duke stated that his time on the Moon “lasted for three days. But a walk with Jesus lasts forever.” Now 89 years old, Charlie Duke still attends church regularly.

Apollo 17

Apollo 17 (1972) broke the mold a bit. Gene Cernan commanded the mission and Harrison “Jack” Schmidt, a geologist and the only scientist to fly on Apollo, was the lunar module pilot. Unlike the other 11 moonwalkers, Schmidt was not a military pilot before becoming an astronaut. After NASA, Cernan had a career in the petroleum industry and was a frequent commentator on spaceflight for news media. Schmidt later ran for, and won, a Senate seat in New Mexico and worked extensively as a consultant. Schmidt, alone among the lunar module pilots, appears not to have undergone a radical transformation after his flight. This may be due to the fact that, as a geologist on the Moon, he was totally immersed in the work of analyzing and collecting Moon rocks and soil samples and, like the mission commanders, may have simply been too mentally engaged during his moonwalks to have been affected by it emotionally. In his autobiography, The Last Man on the Moon, Cernan emphasizes Schmidt’s total commitment to geology.

Many theories

So why did the astronauts’ experiences after the Moon seem so determined by their seat (or rather their role)? Perhaps the commanders, with far more work to do and bearing the bulk of the responsibility for the landing, were simply too busy with all of their tasks to let the experience sink in and affect them. The lunar module pilots, although busy, had far less to do and perhaps simply had more time to look out the literal (and metaphorical) window, thus experiencing the Moon landing and the moonwalks in a deeper and more life-altering manner, illustrating just how profound such an experience could be.

There’s no way to know for sure, of course, but collectively, these crews and their experiences on the Moon show how transformative and deeply impactful such an experience can be – if you let it.