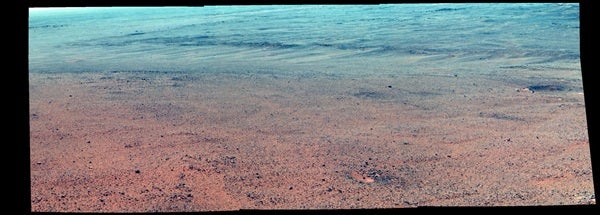

Mars, like Earth, is tilted on its rotation axis with respect to its orbit around the Sun. Its tilt is about 25 degrees, while Earth is tilted about 23.5 degrees, so the two planets experience similar seasons — but Mars, with its 1.88-Earth-year-long year, has seasons that last almost twice as long. That makes planning for power acquisition (via solar panels) and usage (through driving and data collecting) essential during the winter season, when sunlight is scarce and the Sun takes a northern path through the sky from the rover’s point of view. To gain power for mission-necessary tasks, the rover must tilt itself northward to catch as much sunlight as possible during the long winter season.

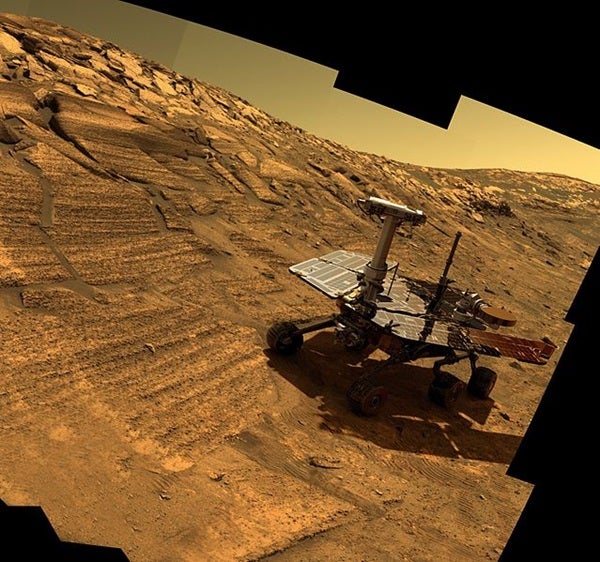

Opportunity is currently exploring a valley known as “Perseverance Valley” on the western rim of Endurance Crater. It’s been there for about five months, and the location puts it in an ideal spot to catch the northern Sun. As it stops to collect valuable photons at planned sites nicknamed “lily pads,” the rover takes the time to explore the immediate area, studying rocks along the crater’s rim and imaging the valley in great detail.

Currently, Opportunity’s panels are relatively clean, but there’s a potential dust storm season approaching next year, so mission planners are remaining optimistic but watchful. “If Opportunity’s solar arrays keep getting cleaned as they have recently, she’ll be in a good position to survive a major dust storm. It’s been more than 10 Earth years since the last one and we need to be vigilant,” said Jennifer Herman, who leads Opportunity’s power subsystem operations team at NASA’s Jet Propulsion Laboratory, in a press release.

This coming January will mark the 14th (Earth-year) anniversary of the Opportunity and Spirit rovers, which were designed to last about three months. Instead, Opportunity is still going strong, though Spirit became stuck in a sand trap and was unable to tilt northward during its fourth winter in 2009. Spirit’s mission was ultimately ended in May 2011, but Opportunity persists — as does the Curiosity rover, which doesn’t rely on solar power, but instead has a radioisotope thermoelectric generator to provide power.