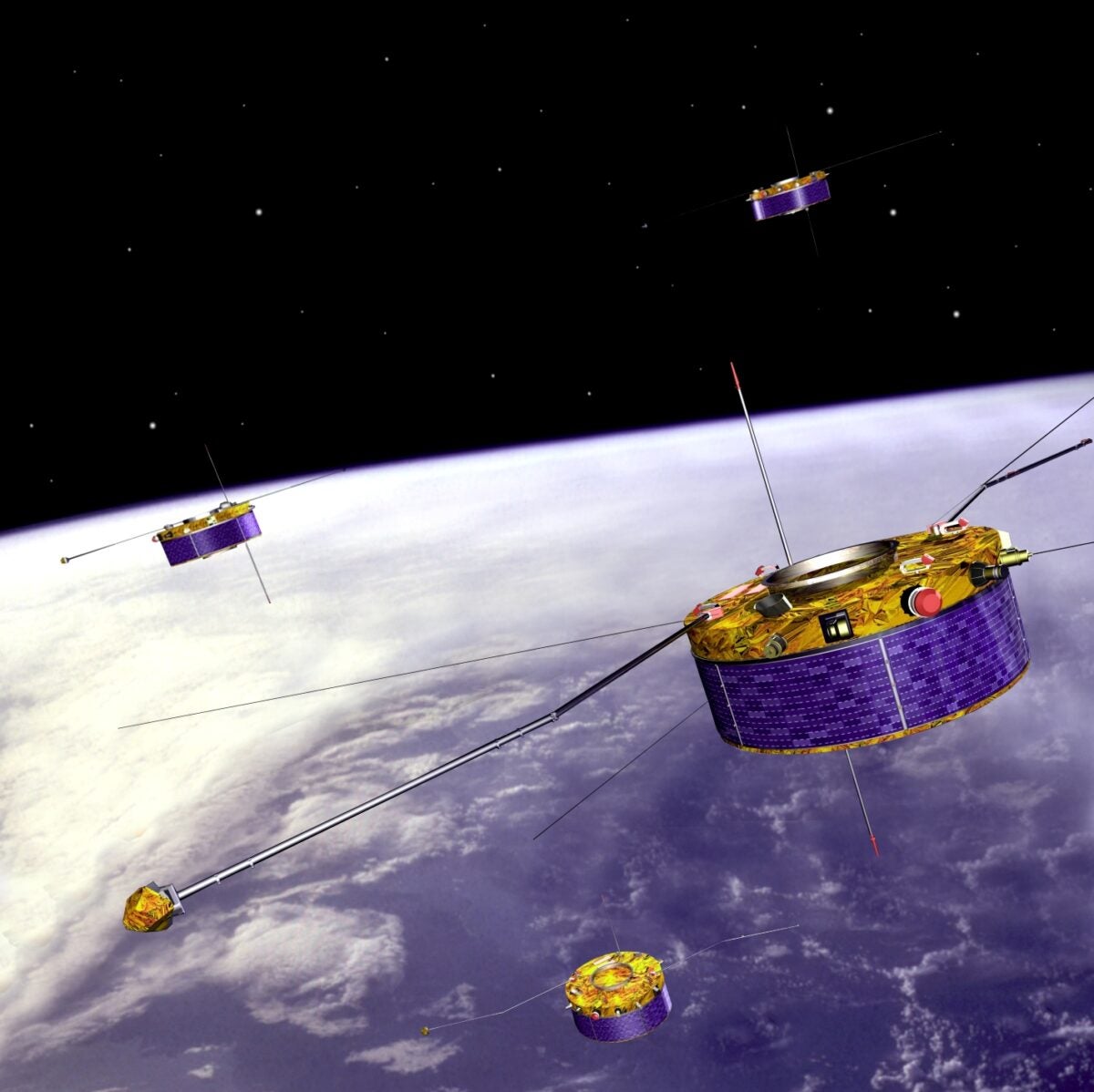

On July 26, 2000, the European Space Agency (ESA) launched the Salsa satellite, which joined its three companion satellites — Samba, Rumba, and Tango — on the Cluster II mission, scheduled to last two years. On Sep. 8, after more than 24 years of service, Salsa re-entered Earth’s atmosphere in a controlled de-orbit, where it broke up over the South Pacific Ocean.

Cluster II was designed to study Earth’s magnetic field, especially how the solar wind interacts with it to produce aurorae and geomagnetic storms. The satellites investigated charged particles and magnetic fields across enormous swaths of the magnetosphere from as close as 10,000 miles (16,000km) above Earth’s surface out to 120,000 miles (75,000km) — roughly halfway to the Moon.

Related: Are we ready for the next big solar storm?

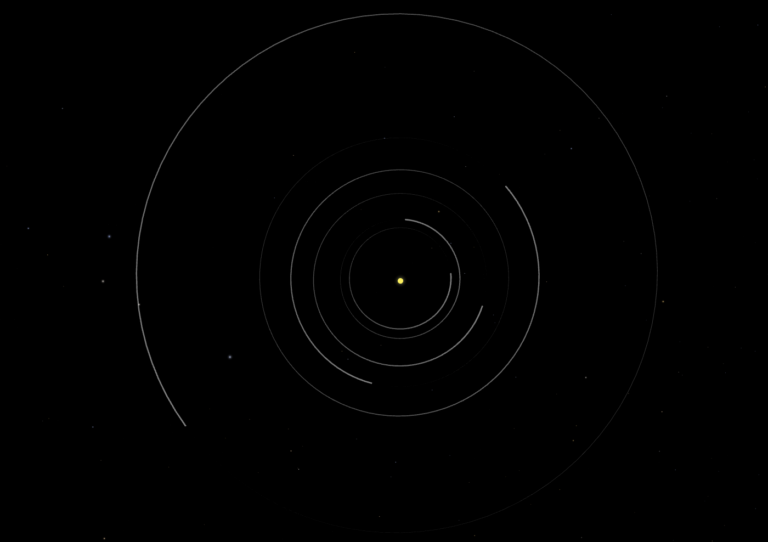

Cluster II was a near-identical replacement to the original Cluster mission, which was destroyed in a failed launch in 1996. The identical, spinning, drum-shaped satellites of Cluster II flew in a tetrahedral formation and could maneuver frequently, sometimes bunching as close as 2.5 miles (4 kilometers), but usually spreading out across some 6,200 miles (10,000 km) in space.

Each craft carried a suite of instruments for measuring the energy and density of charged particles and electromagnetic fields and waves, and performing analysis on the stormy space weather the craft sailed through.

The goal of these instruments was to study the small-scale structure of Earth’s plasma environment, especially the solar wind-magnetosphere interaction. In particular, the mission was designed to map and study the various ways in which Earth’s magnetotail region altered its magnetic field and plasma conditions during the passage of a coronal mass ejection, a burst of material the Sun occasionally flings into space at high speeds.

During severe geomagnetic storms, particle and field conditions vary rapidly in both time and space, which makes in-situ measurements critical in understanding this activity. Cluster II performed those measurements with aplomb, providing data across more than two full cycles of increasing and decreasing solar activity (a solar cycle is roughly 11 years). Researchers will be mining the data for years to come.

Flying in formation

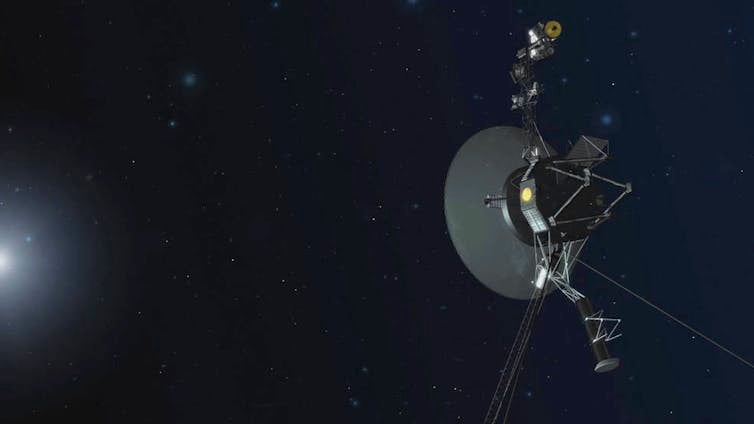

Cluster II wasn’t the first or the last mission that consisted of individual satellites operating in a flying constellation. Noteworthy among these are the Geostationary Operational Environmental Satellites (GOES), which have been periodically updated and replaced since the first launch in 1975. GOES is responsible for tracking space weather and Earth’s atmosphere, and has even aided in search and rescue missions.

The five satellites of NASA’s Time History of Events and Macroscale Interactions during Substorms (THEMIS) mission were launched in 2007 to study magnetic reconnection in Earth’s magnetic field. The NASA mission could vary the separation distance of the maneuverable identical satellites to study many different scales of the magnetic reconnection phenomenon. While three of the satellites remain in Earth orbit, two now orbit the Moon, to study space weather there.

And of course many communication satellites fly in formation, from GPS to Starlink, to provide coverage across Earth’s surface.

A good life

Cluster II was not designed to be operational forever. A satellite like Salsa at the end of its lifetime cannot be allowed to remain in space to become debris for another spacecraft to bump into, nor allowed burn up in the atmosphere by mere chance, its pieces possibly falling on populated areas. So ground controllers performed a series of maneuvers to send Salsa into a controlled re-entry Sep. 8.

Related: Small, untrackable pieces of space junk are cluttering low Earth orbit

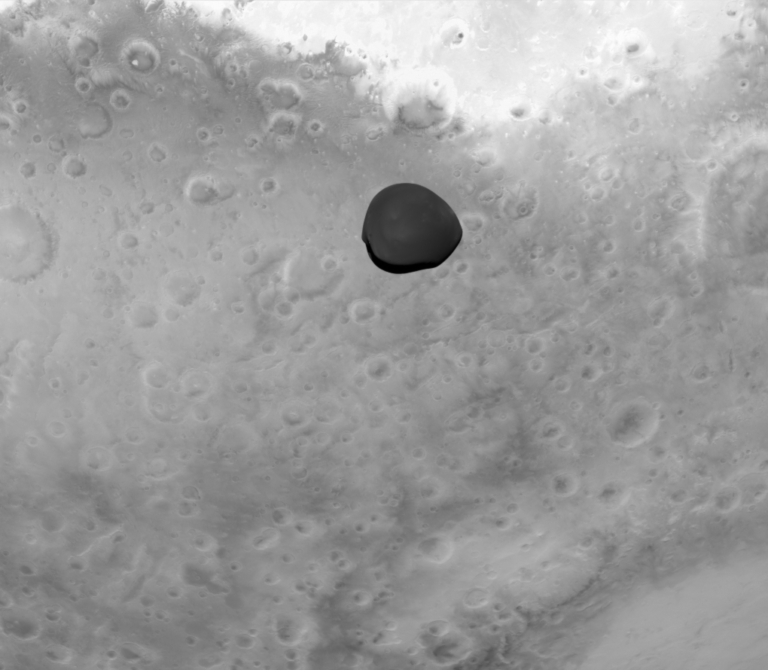

Even during their last months of operation and atmospheric re-entry, the four Cluster II satellites gave scientists a ring-side seat to observe the mysterious region where charged particles are accelerated before producing the polar aurora. These regions are too high for study by balloon payloads and too low to be studied by spacecraft in stable low Earth orbits.

The remaining spacecraft of the Cluster II constellation will be de-orbited over the next two years, but with Salsa’s re-entry, the mission’s science operations have ended. Over 3,200 research papers have been written and published so far about the Cluster II science accomplishments, and they will surely continue to provide insight for years to come.