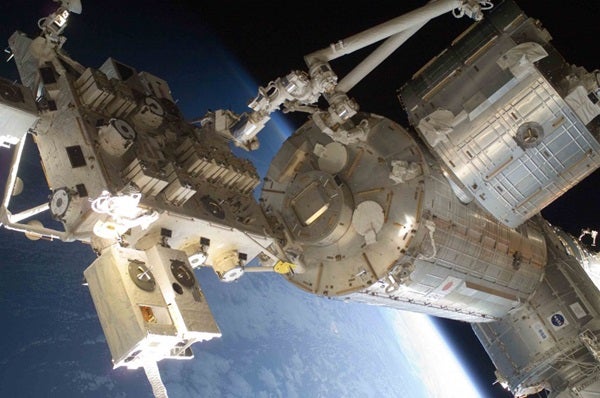

Now Japan has taken a first step toward answering some of these questions thanks to a new instrument in their KIBO module on the ISS. Called MARS – Multiple Artificial-gravity Research System – it can spin to produce gravity at a variety of levels. Scientists have used it to raise mice in microgravity, artificial Earth gravity, and artificial lunar gravity. Then, they compared the mice to those raised in a similar habitat on the ground in true Earth gravity.

Mice in Space!

The experimental mice were reared in space for a month before returning to Earth for study. All the mice survived their time on station and the trip back to the ground. Upon returning to Earth, the mice were dissected to check their growth rates and internal organs.

The first round of experiments, back in 2017, compared the mice raised in artificial Earth gravity and microgravity to those raised on Earth. Scientists found that the ones raised with gravity – real or artificial – seemed to do fine. But the mice raised in microgravity suffered from loss of bone density and muscle mass compared to the other mice.

That’s pretty normal. Experiments on both mice and humans have proven this over more than half a century of spaceflight. But it was still helpful to prove that mice raised in artificial gravity could do as well as those raised with the real deal on the ground.

The second round of the experiment saw mice raised in simulated lunar gravity. That experiment just ended, and the mice returned to Earth in June on one of SpaceX’s Dragon capsules. After collecting the mice from the capsule, researchers shipped them to Japan for study.

Throughout the experiments, researchers could watch their mice on video to see how they behaved in space. Aside from the physical changes already measured in the microgravity mice, both these rodents and the lunar-gravity mice adapted their behaviors to their strange environments. They learned to maneuver, feed, and groom themselves with light or no gravity, just as humans have. The mice in artificial Earth gravity stood and ate normally, while those in microgravity learned to eat while floating, and those in artificial lunar gravity learned to wait until they had drifted to the ground before eating.

The truly valuable results will come once scientists have had time to analyze the samples from the mice raised in artificial lunar gravity. Until now, most tests have been essentially all-or-nothing when it comes to gravity, and that’s not what humans will deal with on the Moon or Mars. But the fact that all the mice survived their month in space, regardless of the gravity of their situation, is already a good sign.