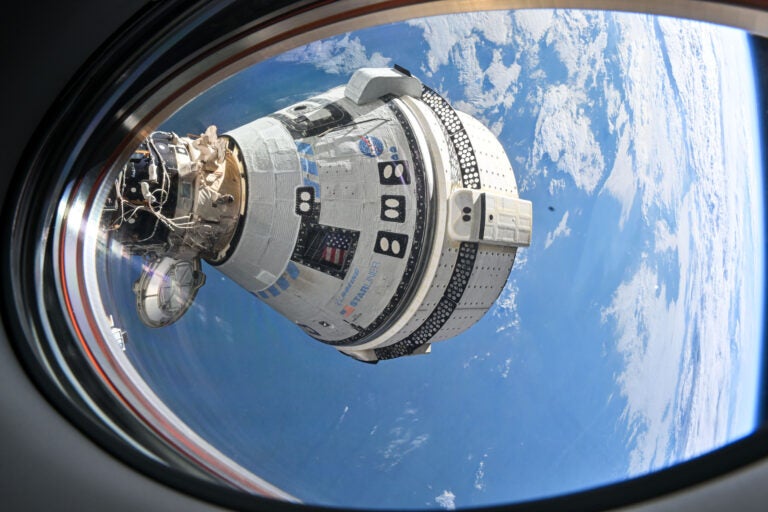

Based on data the group obtained with an instrument aboard the Lunar Reconnaissance Orbiter (LRO), NASA chose the impact site for the LCROSS probe, which slammed into the Moon’s surface last year in October 2009 in an attempt to kick up dust that could be analyzed for the presence of water ice.

“We found significant amounts of water around the north and south poles, in places where previously we were only tentatively thinking of it,” said Boynton.

In addition to confirming water and its distribution in unprecedented detail, the data included an unexpected finding.

“To our surprise, some of the permanently shadowed regions had no water, but some of the areas that receive sunlight occasionally did have water,” Boynton said.

In other words, water was found not only where it is supposed to be, but also where it is not supposed to be.

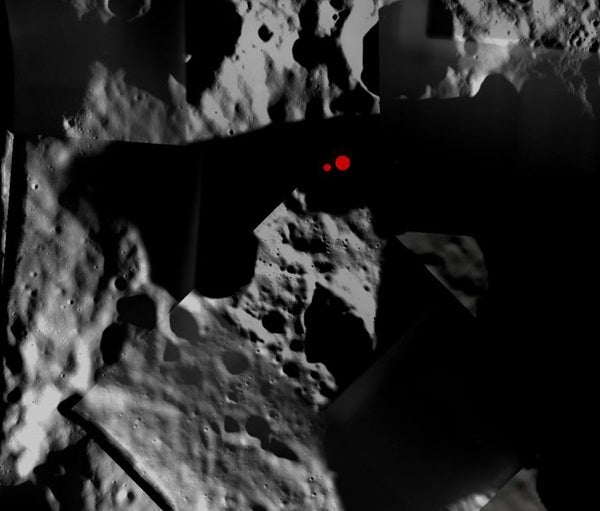

Previously, scientists were convinced water ice could only persist in so-called permanently shadowed regions (PSRs) on the Moon’s surface the Sun never reaches. Unlike Earth, whose tilted axis ensures that any spot on the surface receives at least some sunlight at some point during the planet’s yearlong journey around the Sun, the Moon’s axis is hardly tilted at all. As a result, some places on the lunar surface are never exposed to sunlight.

“In some of the craters that are close to the north or south pole and have very steep walls, no direct sunlight ever reaches the bottom of the crater,” Boynton said.

“At down to -370° Fahrenheit (-223° Celsius), those PSRs are colder than Pluto, even at noon,” added Karl Harshman from the Lunar and Planetary Lab at the University of Arizona.

But according to the measurements the group obtained using the Lunar Exploration Neutron Detector (LEND) aboard the LRO spacecraft orbiting the Moon, there is water even in areas that are exposed to the Sun’s warming rays every once in a while. Conversely, some of the PSRs turned out to be completely dry.

The data also helped to obtain a more detailed picture of water distribution on the Moon.

“The data we obtained in the first 3 months of the mission helped LCROSS select the impact site,” said Gerard Droege, a data analyst in Boynton’s group who created the visual representations of the data. “It gave mission control just enough time to tweak the trajectory, and everybody then said, OK, we’re going for Cabeus.”

“Previous instruments could only tell us that the whole area around the poles is enriched, now our knowledge is much more spatially refined,” Boynton said.

To trace the abundance of water on the Moon, the scientists took advantage of cosmic particles constantly bombarding every object in space. Since the Moon lacks a protective atmosphere, the particles strike the surface close to the speed of light. When they collide with the atomic nuclei in the dusty soil they knock particles off these atoms, mostly protons and neutrons, some of which escape into space. If one of these particles hits a hydrogen atom, which is most likely part of a water molecule, it slows down dramatically, leaving fewer particles fast enough to escape to space.

By measuring differences in the flow of neutrons coming from the Moon’s surface, the researchers were able to infer the amount of water present in the soil: Areas emitting low neutron radiation indicated water capturing and retaining most of the neutrons, while areas reflecting high neutron radiation identified themselves as dry.

In the PSRs near the impact site in the Cabeus crater near the Moon’s south pole, the soil was found to contain up to four percent water.

“The water might be like some form of ice mixed in with the soil, possibly similar to the slightly damp, frozen soil found in Alaska,” Boynton said. “We think that in the PSRs, water ice might be present on the surface, but the fact we found it in the partially sunlit areas, too, means the upper three inches or so must be dry dirt, otherwise the sunlight would cause the water to evaporate.”

Possible origins of the water on the Moon include impacts of icy comets or hydrogen deposited from solar wind, the authors noted.

Based on data the group obtained with an instrument aboard the Lunar Reconnaissance Orbiter (LRO), NASA chose the impact site for the LCROSS probe, which slammed into the Moon’s surface last year in October 2009 in an attempt to kick up dust that could be analyzed for the presence of water ice.

“We found significant amounts of water around the north and south poles, in places where previously we were only tentatively thinking of it,” said Boynton.

In addition to confirming water and its distribution in unprecedented detail, the data included an unexpected finding.

“To our surprise, some of the permanently shadowed regions had no water, but some of the areas that receive sunlight occasionally did have water,” Boynton said.

In other words, water was found not only where it is supposed to be, but also where it is not supposed to be.

Previously, scientists were convinced water ice could only persist in so-called permanently shadowed regions (PSRs) on the Moon’s surface the Sun never reaches. Unlike Earth, whose tilted axis ensures that any spot on the surface receives at least some sunlight at some point during the planet’s yearlong journey around the Sun, the Moon’s axis is hardly tilted at all. As a result, some places on the lunar surface are never exposed to sunlight.

“In some of the craters that are close to the north or south pole and have very steep walls, no direct sunlight ever reaches the bottom of the crater,” Boynton said.

“At down to -370° Fahrenheit (-223° Celsius), those PSRs are colder than Pluto, even at noon,” added Karl Harshman from the Lunar and Planetary Lab at the University of Arizona.

But according to the measurements the group obtained using the Lunar Exploration Neutron Detector (LEND) aboard the LRO spacecraft orbiting the Moon, there is water even in areas that are exposed to the Sun’s warming rays every once in a while. Conversely, some of the PSRs turned out to be completely dry.

The data also helped to obtain a more detailed picture of water distribution on the Moon.

“The data we obtained in the first 3 months of the mission helped LCROSS select the impact site,” said Gerard Droege, a data analyst in Boynton’s group who created the visual representations of the data. “It gave mission control just enough time to tweak the trajectory, and everybody then said, OK, we’re going for Cabeus.”

“Previous instruments could only tell us that the whole area around the poles is enriched, now our knowledge is much more spatially refined,” Boynton said.

To trace the abundance of water on the Moon, the scientists took advantage of cosmic particles constantly bombarding every object in space. Since the Moon lacks a protective atmosphere, the particles strike the surface close to the speed of light. When they collide with the atomic nuclei in the dusty soil they knock particles off these atoms, mostly protons and neutrons, some of which escape into space. If one of these particles hits a hydrogen atom, which is most likely part of a water molecule, it slows down dramatically, leaving fewer particles fast enough to escape to space.

By measuring differences in the flow of neutrons coming from the Moon’s surface, the researchers were able to infer the amount of water present in the soil: Areas emitting low neutron radiation indicated water capturing and retaining most of the neutrons, while areas reflecting high neutron radiation identified themselves as dry.

In the PSRs near the impact site in the Cabeus crater near the Moon’s south pole, the soil was found to contain up to four percent water.

“The water might be like some form of ice mixed in with the soil, possibly similar to the slightly damp, frozen soil found in Alaska,” Boynton said. “We think that in the PSRs, water ice might be present on the surface, but the fact we found it in the partially sunlit areas, too, means the upper three inches or so must be dry dirt, otherwise the sunlight would cause the water to evaporate.”

Possible origins of the water on the Moon include impacts of icy comets or hydrogen deposited from solar wind, the authors noted.