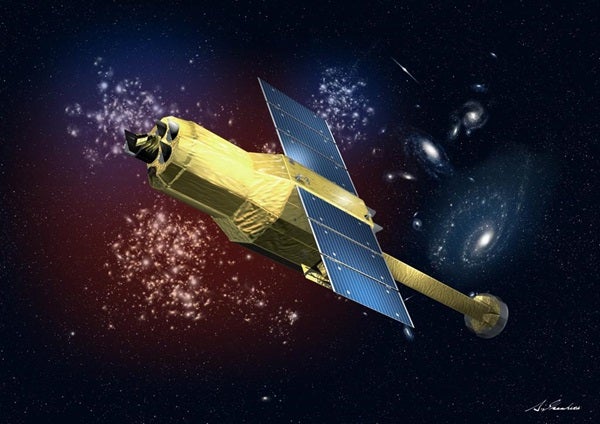

Earlier this year, the X-ray astronomy community experienced the highs of a successful observatory launch followed only a month later with the lows of that spacecraft’s demise. This was the Japanese-led Hitomi X-ray space telescope, and it was supposed to shed light on the high-energy processes of the universe. Instead, it broke apart shortly after giving astronomers a taste of what the craft could do. Its loss is a major hit to X-ray astronomers, but if the current talks pan out, we might see Hitomi version 2.0 launch in 2020 or 2021.

A bit of history

Here’s a short reminder about what happened earlier this year. ASTRO-H launched smoothly February 17 into its circular orbit around Earth. (As with other missions from the Japanese Aerospace Exploration Agency [JAXA], the ASTRO-H observatory was renamed just after launch. Its new name became Hitomi.) Everything appeared stable until March 26, when JAXA couldn’t communicate with the craft. Something was wrong.

We now know that after Hitomi had reoriented to observe a new target, a software error combined with human error caused the craft to misunderstand its rotation, which sent it rotating out of control. Several pieces of the spacecraft snapped off, including the solar panels and the optics portion that extended out from the main body. Losing these pieces was detrimental. Without solar panels Hitomi can’t collect energy to power the observatory. After investigating the March 26 events, JAXA announcedApril 28 that there was no way to restore the mission.

Why it mattered

The first time I heard about ASTRO-H was actually pretty late in its development. It was at a high-energy astrophysics meeting in April 2013, when X-ray astronomers were excitingly planning their observing projects.

ASTRO-H’s main instrument, the Soft X-ray Spectrometer (SXS), would revolutionize our view of the high-energy sky. The SXS would detect individual packets of X-ray light, and directly measure the heat of each of those X-ray photons. Scientists would know, for example how intense different regions of a gas cloud is at each X-ray energy. From that data, astronomers could piece together the movement of the object — mapping gas clumps of different elements flying out from the site of a stellar explosion or the motions of colliding galaxy clusters.

Other telescopes — like NASA’s Chandra and Europe’s XMM-Newton — have X-ray spectrometers, but those work differently. They spread the light into a rainbow, and can get detailed information on only point sources (like a bright star or distant active galaxy). The SXS could get an array of detail from several areas within an object (studying, for example, the winds near the center of a large galaxy). Plus, the SXS would be some 30 times as sensitive as any other space X-ray spectrometer.

It was ASTRO-H’s bread and butter. And it was a type of observation that X-ray astronomers desperately wanted.

The soft X-ray Spectrometer’s detector array (a microcalorimeter, the gray-and-gold square at the center) measures just half a centimeter across. (Credit: NASA’s Goddard Space Flight Center)

This year’s high-energy astrophysics meeting took place the first week of April and just days after Hitomi’s communication failure. Instead of an upbeat session showcasing the progress of the spacecraft, team member Andy Fabian of the University of Cambridge, updated the X-ray astronomy community about the situation. “This is extremely sad and distressing for the enormous team working on this,” he said. The air in the room was heavy, gloomy.

During its five functioning weeks, Hitomi gave astronomers a taste of what the SXS instrument could have delivered. The observatory watched the bright center of the Perseus cluster of galaxies, and the collected data, said Fabian during this same presentation, “are completely transformational.” (The Hitomi team published these observations in a recent Nature paper.)

What’s next?

Even though Hitomi is completely lost, neither JAXA nor NASA are giving up on the idea of a successor mission.

A July 14 presentation from the JAXA Space Science Institute Director Tsuneda Saku overviews a suggested mission. (Unfortunately, thepresentation PDF is in Japanese, and thus I had to rely on Google translate and similar apps.) From what I can make out, this observatory’s focus would be the SXS instrument. The spacecraft’s body and design would mimic Hitomi’s, which would therefore speed up development and construction. The launch goal is 2020 — if the mission and its funding is approved. During a July 15 press conference, the Japanese Minister of Education, Culture, Sports, Science and Technology Hiroshi Hase spoke of his support for a successor to Hitomi.

But even if JAXA does get approval to build Hitomi version 2.0, they need NASA’s involvement. That’s because JAXA wasn’t responsible for the main instrument — America’s space agency was.

That’s where the NASA X-ray Science Interest Group comes in. On June 8, the group of about 75 researchers discussed whether NASA might participate in a subsequent flight. In the weeks since, the group compiled a white paper to support the science case, and that was presented at a NASA Advisory Council Astrophysics Subcommittee meeting over the past two days. The science case is there — no one doubts that.

There is no X-ray instrument like the SXS in space right now. The European-led mission scheduled for a 2028 launch, Athena, will carry a similar instrument, but that’s a long time to wait for the views that X-rays astronomers had hoped to have now. If NASA and JAXA decide to move forward on a Hitomi successor with the SXS, the project could launch in 4 to 5 years. Both agencies will meet early next month to talk further about collaborating on a possible re-fly.

No scientist ever wants his or her experiment to go wrong. I’ve seen the disappointment before, for different astronomical projects; it’s heartbreaking. “There’s no question we went through the five stages of grief when we first heard about the spacecraft,” says NASA X-ray Science Interest Group Chair Mark Bautz.

Astronomers spend years, sometimes a lot longer, developing the hardware and the software to run said hardware, plus the subsequent observing plan. “We’ve been waiting for this for decades — literally,” says Harvard X-ray astronomer Randall Smith, who is unaffiliated with Hitomi, “and to get a small taste and then lose it has just been awful.”

In space science, you usually get one shot. Maybe ASTRO-H will get a second.

This post originally appeared at Discover Magazine.